Lima, Peru: Backdraft

December 24th, 2010I recently traveled to Peru to deliver a presentation on 3D Firefighting at the First International Congress on Emergency First Response which was conducted by the Cuerpo General de Bomberos Voluntarios del Perú. This congress was being conducted in conjunction with the Peruvian fire service’s 150th anniversary celebration (establishment of Unión Chalaca No. 1, the first fire company).

In addition to my conference presentation, I spent 10 days teaching fire behavior and working alongside the Bomberos of Lima No.4, San Isidro No. 100, and Salvadora Lima No. 10.

Fire & Rescue Services in Lima, Peru

Lima is a city of 8 million people served by a volunteer fire service which provides fire protection, emergency medical services, hazmat response, and urban search and rescue. The stations that I worked in were busy with call volumes from 2000 to 5000 responses in an urban environment ranging from modern high-rise buildings to poor inner city neighborhoods. Each station was equipped with an engine, truck, rescue, and ambulance. Staffing varied throughout the day with some units being cross staffed or un-staffed due to limited staffing. At other times, units were fully staffed (5-6 on engines and trucks, 4 on rescues, and 3 on ambulances). While the Peruvian fire service has some new apparatus, many apparatus are old and suffer from frequent mechanical breakdown. Faced with high call volume and old apparatus and equipment, the Firefighters and Officers displayed a tremendous commitment to serve their community.

The firefighters I encountered had a tremendous thirst for knowledge and commitment to learning. My friend Giancarlo had arranged for a short presentation on fire behavior for a Tuesday evening and the room was packed. Class was scheduled from 20:00 until 22:00. However, when we reached 22:00, the firefighters wanted to stay and continue class. We adjourned at 24:00. This continued for the next two nights. Sunday, between calls, we had breakfast at San Isidro No. 100 and then conducted a hands-on training session on nozzle techniques and hose handling. At the start of class, Firefighter Adryam Zamora from Santiago Apostol No. 134, related that he used the 3D techniques we had discussed in class at an apartment fire the night before with great success.

Staff Ride

Staff rides began with the Prussian Army in the mid-1800s and are used extensively by the US Army and the US Marine Corps. A staff ride consists of systematic preliminary study of a selected campaign or battle, an extensive visit to the actual sites associated with that campaign, and an opportunity to integrate the lessons derived from these elements. The intent of a staff ride is to put participants in the shoes of the decision makers on a historical incident in order to learn for the future. Wildland firefighters have adapted the staff ride concept and have used it extensively to study large wildland fires, fatalities, and near miss incidents. However, structural firefighters have not as commonly used this approach to learning from the past.

When I traveled to Lima, I only knew two Peruvians; Teniente Brigadier CBP (a rank similar to Battalion Chief in the US fire service) Giancarlo Passalaqua and Teniente CBP (Lieutenant) Daniel Bacigalupo. However, I left Lima with a much larger family with many more brothers and sisters.

Backdraft!

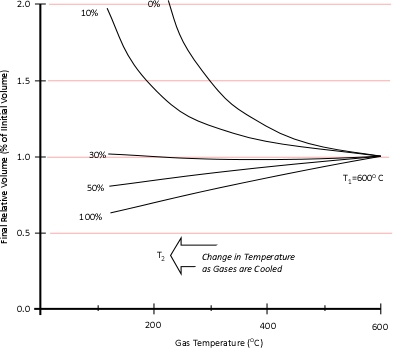

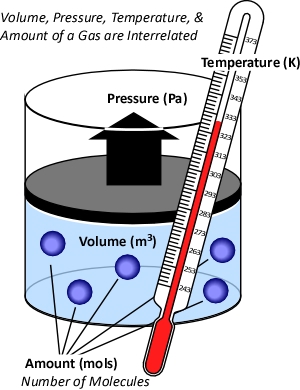

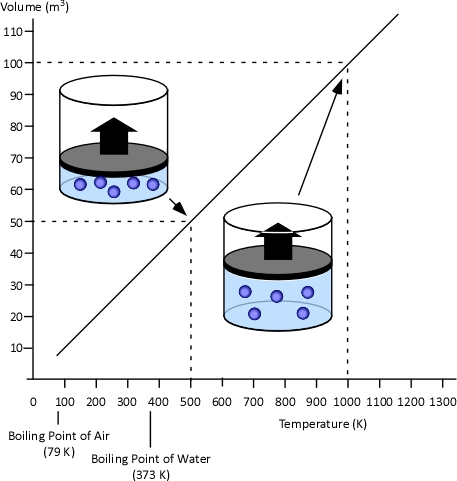

Many firefighters have seen the following video of an extreme fire behavior event that occurred in Lima, Peru. This video clip often creates considerable discussion regarding the type of fire behavior event involved and exactly how this might have occurred. Photos and video of fire behavior are a useful tool in developing your understanding and developing skill in reading the fire. However, they generally provide a limited view of the structure, fire conditions, and incident operations.

Note: While not specified in the narrative, this video is comprised of segments from various points from fairly early in the incident (see Figure 3, to later in the incident immediately before, during, and after the backdraft).

When I was invited to Lima, I asked my friend Teniente Brigadier CBP Giancarlo Passalaqua who worked at this incident, if it would be possible to talk to other firefighters who were there and to walk the ground around the building to gain additional insight into this incident.

The Rest of the Story

The morning after I arrived, I was sitting in the kitchen of San Isidro No. 100 and was joined in a cup of coffee by Oscar Ruiz, a friendly and engaging man in civilian clothing who I assumed was a volunteer firefighter at the station. After my friend Giancarlo arrived, he told me that Oscar was actually Brigadier CBP (Deputy Chief) Oscar Ruiz from Lima No. 4 and one of the two firefighters who had been in the bucket of the Snorkel pictured in the video. Oscar and I had several opportunities to spend time together over the course of my visit and he shared several observations and insights into this incident.

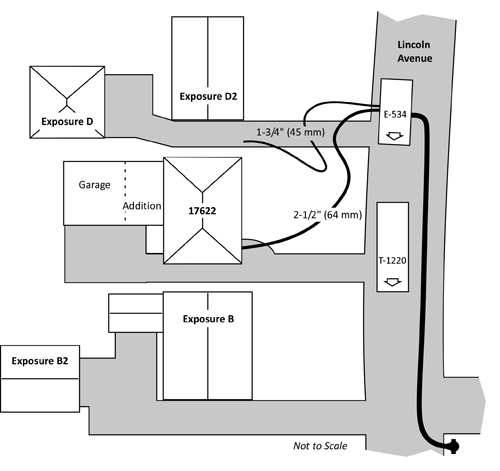

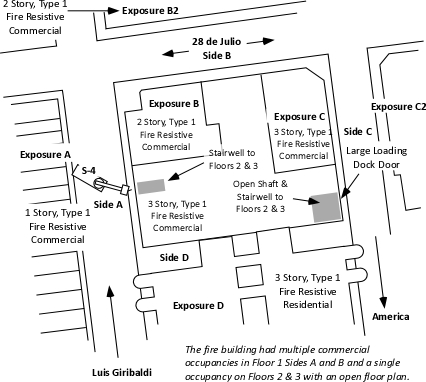

At 11:00 hours on Saturday, March 15, 1997, two engines, a ladder, heavy rescue, medic unit, and command officer from the Lima Fire Department were dispatched to a reported commercial fire at the intersection of Luis Giribaldi Street and 28 de Julio Street in the Victoria section of Lima.

Companies arrived to find a well developed fire on Floor 2 of a 42 m x 59 m (138’ x 194’) three-story, fire resistive commercial building, The structure contained multiple, commercial occupancies on Side A (Luis Giribaldi Street) and Side B (28 De Julio Street). Floors 2 and 3 were used as a warehouse for fabric (not as a plastics factory as reported in the video clip). The building was irregularly shaped with attached exposures on Sides B and C.

Exposure A was a complex of single-story commercial occupancies, Exposure B was an attached two-story commercial complex, Exposure C was an attached three story commercial complex, and Exposure D was a three story apartment building. All of the exposures were of fire resistive construction.

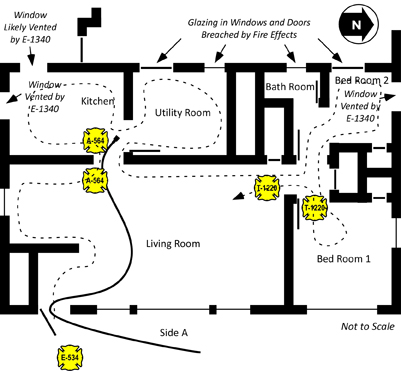

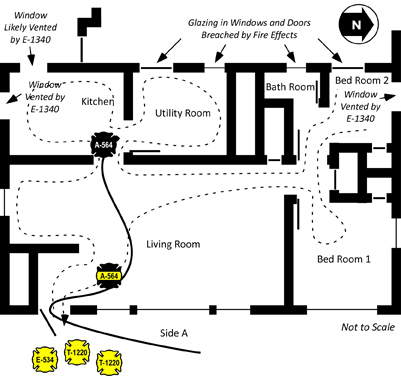

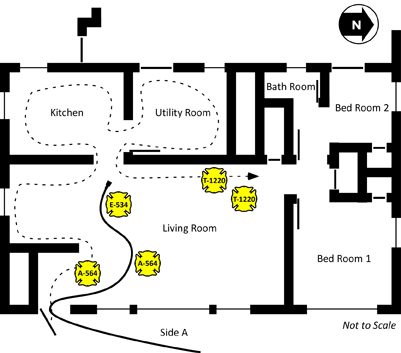

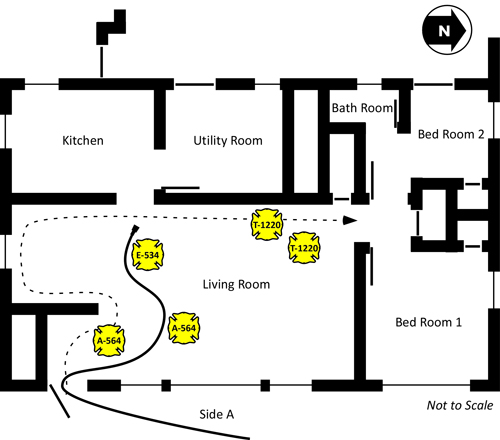

Figure 1. Plot Plan

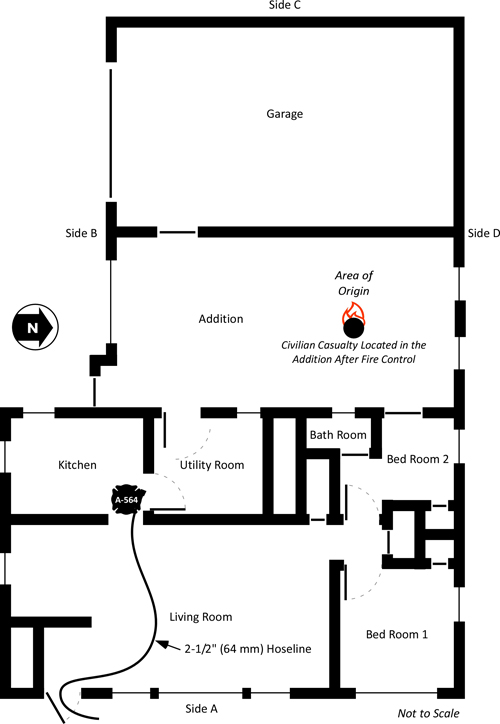

Floors 2 and 3 had an open floor plan and were used for storage of a large amount of fabric and other materials. As illustrated in Figure 1, there were two means of access to Floors 2 and 3; a stairway on Side A and an open shaft and stairway on Side C.

Due to heavy fire involvement, operations focused on a predominantly defensive strategy to control the fire in this multi-occupancy commercial building. The incident commander called for a second, and then third alarm. Defensive operations involved use of handlines and an aerial ladder working from Side A and in the Side A stairwell leading to Floor 2. However, application of water from the ladder pipe had limited effect (possibly because of the depth of the building and burning contents shielded from direct application from the elevated stream.

Figure 2. Early Defensive Operations

Note: Video screen shot from the intersection of Luis Giribaldi and 28 de Julio.

The third alarm at 14:05 hours brought two engines and articulating boom aerial platform (Snorkel) from Lima 4 to the incident. Snorkel 4, under the command of Captain Roberto Reyna was tasked to replace the aerial ladder which had been operating on Side A and operate an elevated master stream to control the fire on Floor 2 (Figure 2).

Placing their master stream into operation Teniente Oscar Ruiz and Captain Roberto Reyna worked to darken the fire on Floor 2. As exterior streams were having limited effect, Snorkel 4 was ordered to discontinue operation and began to lower the bucket to the ground. At the same time, efforts were underway to gain access to the building from Side C. Using forcible entry tools, firefighters breached the large loading dock door leading to the vertical shaft and stairwell in the C/D quadrant of the building.

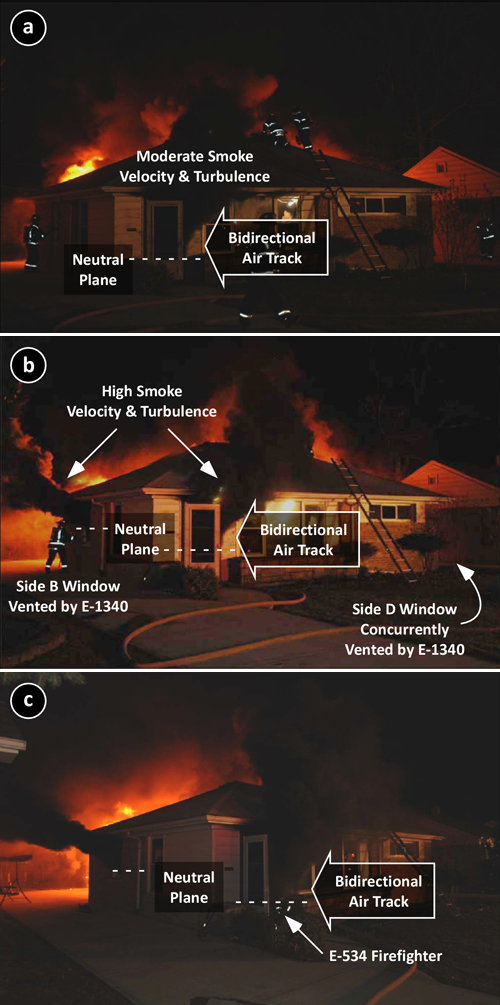

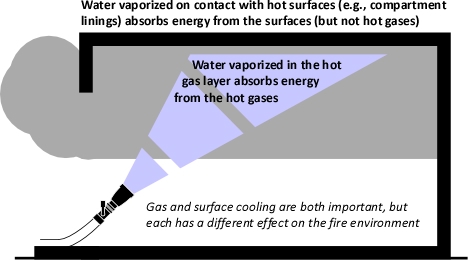

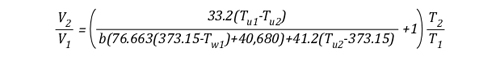

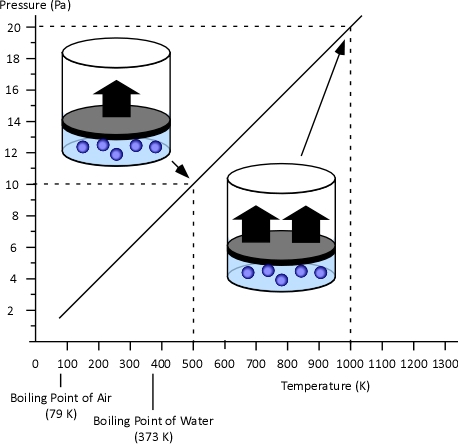

Prior to opening the large loading dock door on Side C (Charlie/Delta Corner), a predominantly bi-directional air track is visible at ventilation openings on Side C. Flaming combustion from windows on Side A was likely limited to the area at openings with a bidirectional air track. Combustion at openings on Side A likely consumed the available atmospheric oxygen, maintaining extremely ventilation controlled conditions with a high concentration of gas phase fuel from pyrolyzing synthetic fabrics deeper in the building.

The ventilation profile when Snorkel 4 initially began operations included intake of air through the open interior stairwell (inward air track) serving floors 1-3 and from the lower area of windows which were also serving as exhaust openings (bi-directional air track). Interview of members operating at the incident indicates that there were few if any ventilation openings (inlet or exhaust) on Sides B, C, or D prior to creation of an access opening on Floor 1 Side C.

At approximately 15:50, Snorkel 4 was ordered to stop flowing water. As smoke conditions worsened, they did so and began to lower the aerial tower to the ground. At the same time, crews working to gain access to Floor 1 on Side C, breached the large loading dock door. A strong air track developed, with air rushing in the large opening and up the open vertical shaft leading to the upper floors as illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Layout of Floors 1 and 2

As the Snorkel was lowered to the ground, Teniente Oscar Ruiz observed a change in smoke conditions, observing a color change from gray/black to “phosphorescent yellow” (yellowish smoke can also be observed in the video clip of this incident). Less than two minutes after the change in ventilation profile, a violent backdraft occurred, producing a large fireball that engulfed Captain Roberto Reyna and Teniente Oscar Ruiz in Snorkel 4 (see Figure 4). The blast seriously injured the crew of Snorkel 4 along with numerous other members from stations Lima 4, Salvadora Lima 10, and Victoria 8 who were located in the Stairwell (these members were blown from the building) and on the exterior of Side A.

This incident eventually progressed to a fifth alarm with 63 companies from 26 of Lima’s 58 stations in attendance.

Figure 4. Backdraft Sequence

Watch the video again; keeping in mind the changes in air track that resulted from breaching the loading dock door on Side C. Consider the B-SAHF (Building, Smoke, Air Track, Heat, and Flame) indicators that are present as the video progresses.

Luis Giribaldi Street and 28 de Julio Street Today

The building involved in this incident is still standing and while it has been renovated, is much the same as it was in 1997. On December 6, 2010, Teniente Brigadier Giancarlo Passalaqua, myself and Capitáin Jordano Martinez went to Luis Giribaldi and 28 de Julio to walk the ground and gain some insight into this significant incident.

Figure 5. Luis Giribaldi Street

As illustrated in Figure 5, Luis Giribaldi Street is a one-way street with parking on both sides and overhead electrical utility lines.

Figure 6. A/D Corner

There are a number of obvious structural changes that have been made since the fire. Including installation of window glazing flush with the surface of the building (the original windows can be seen behind these outer windows).

Figure 7. Snorkel 4’s Position

Figure 7 shows the view from Snorkel 4’s position, just to the left of center is the entry way leading to the stairwell used to access Floors 2 and 3. Piled fabric and other materials can be seen through the windows of Floors 2 and 3, likely similar in nature to conditions at the time of the incident.

Figure 8. Side A

Figure 8 provides a view of Side A and Exposure B, which appears to be of newer construction and having a different roofline than the fire building. The appearance of the left and right sides of the fire building are different, but this is simply due to differences in masonry veneer on the exterior of the building.

Figure 9. A/B Corner

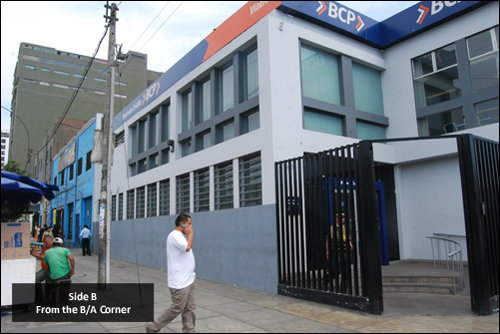

Figure 10. Side B

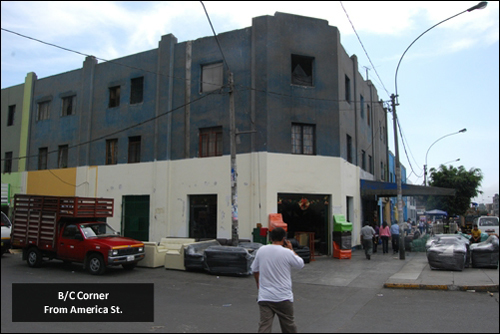

Figure 11. B/C Corner

As illustrated in Figures 10-11 this block is comprised of several attached, fire resistive buildings. It is difficult to determine the interior layout from the exterior as there are numerous openings in interior walls due to renovations and changes in occupancy over time. The floor plan illustrated in Figure 4 is the best estimate of conditions at the time of the fire based on interviews with members operating at the incident.

Figure 12. Side C and the Loading Dock Door

Figure 12shows Side C of the fire building and Exposure C and the loading dock door that was breached to provide access to the fire building from Side C immediately prior to the backdraft.

Figure 13. Side D and Exposure D

Figure 13illustrates the proximity of Exposure D, a three-story, fire-resistive apartment building.

Lessons Learned

This incident presented a number of challenges including a substantial fuel load (in terms of both mass and heat of combustion), fuel geometry (e.g., piled stock), and configuration (e.g., shielded fire, difficult access form Side C). Analysis of data from the short video clip and discussion of this incident with those involved provides a number of important lessons.

- Knowledge of the buildings in your response area is critical to safe and effective firefighting operations. While a challenging task, particularly in a large city such as Lima, developing familiarity with common building types and configurations and pre-planning target hazards can provide a significant fireground advantage.

- Reading the fire is essential to both initial size-up and ongoing assessment of conditions. In this incident, fire behavior indicators may have provided important cues needed to avoid the injuries that resulted from this extreme fire behavior event.

- Some fire behavior indicators can be observed from one position, while others may not. It is particularly important that individuals in supervisory positions be able to integrate observations from multiple perspectives when anticipating potential changes in fire behavior.

- Any opening, whether created for tactical ventilation or for entry has the potential to change the ventilation profile. It is important to consider potential changes in fire behavior that may result from changes in ventilation (particularly when the fire is ventilation controlled).

- Communication and coordination are critical during all fireground operations. It is essential to communicate observations of key fire behavior indicators and changes in conditions to Command. Tactical ventilation (or other tactical operations that may influence fire behavior) must be coordinated with fire attack.

- Protective clothing and self-contained breathing apparatus are a critical last line of defense when faced with extreme fire behavior (even when engaged in exterior, defensive operations).

I would like to recognize the members of the Peruvian fire service who assisted in my efforts to gather information about this incident and identify the important lessons learned. In particular, I would like to thank Teniente Brigadier Giancarlo Passalaqua, Brigadier CBP Oscar Ruiz, and my brothers at Lima 4 who generously shared their home, their time, and their knowledge.

Ed Hartin, MS, EFO, MIFIreE, CFO

When I was invited to Lima, I asked my friend Teniente Brigadier CBP Giancarlo Passalaqua who worked at this incident, if it would be possible to talk to other firefighters who were there and to walk the ground around the building to gain additional insight into this incident.