Mass and Energy Balance in Fire Ventilation

Sunday, March 16th, 2014Milestone! As I was preparing to upload this post, I realized that this is the 200th CFBT-US Blog Post since its inception in August of 2008. Quite a lot has happened since then. In 2008 there were few people in the fire service focused on the importance of fire dynamics to firefighting operations. Today it is a significant research focus and an ongoing topic of discussion throughout the US fire service. Progress is being made, but much remains to be done.

This post focuses on questions posed by firefighters in Europe and North America. Art Arnalich, a Fire Officer from Spain recently sent me a message asking for clarification and further explanation of the application of conservation of mass as it relates to fire ventilation. As always, questions form an excellent basis to examine what we think we know and how it applies in a practical context.

In my previous post, Large Vertical Vents are Good, But…, I stated:

Conservation of Mass: The mass of air entering a compartment (single compartment or building) must equal the mass of smoke and air exiting the building. This means that other than in the extremely short term, if smoke is exiting the building, air must be entering. This may be through one or more openings functioning solely as inlets or openings may be functioning as both inlets and outlets (with either a bi-directional flow or alternating (pulsating) flow). However, the mass of the inflow must equal that of the outflow.

Art writes: The first condition for the Principle of Conservation of Mass to be applied is that the physical system must be closed to all transfers of matter and energy. While a closed compartment could be considered as a nearly “closed system”, a venting structure suffers important transfers of matter and energy. If we were to consider a bigger system (let’s say the 100x100x100m cube in which the house and all of its fire gases are included) the PCM [principle of conservation of mass] applies… Being the structure volume constant, any exiting gases will create an interior drop of pressure that will instantly drag an equal volume of gases to enter. Inlets with the bigger pressure differentials (lower side) will observe the larger flows. Outflow volume must equal inflow volume unless significant pressure changes can take place (not likely). Since there is an important difference between inflow/outflow temperatures (and densities), inflow mass (mass=density x volume) does not equal outflow mass.

The amount of gases coming out of combustion as a result of the new oxygen flow has been disregarded. In an actual fire, outflow volume should be larger than inflow volume because combustion of products generates new gases in within the interior.

But that doesn’t mean that mass in = mass out if we just consider the house. Total mass of unburned air + mass of fuel + mass of all combustion products = constant. But to measure this we can’t consider the volume of the structure itself but the volume that contains all fire gases, unburned gases and the house.

Art Asks: Could you please explain the implications of Principle of Conservation of Mass applies at a molecular level…If Mass-in=Mass-out then there is no mass variation over time (dm/dt=0). This would mean that the total mass of the house before the fire equals its mass after the fire. That doesn’t make sense.

Conservation of Mass and Energy

Mass is neither created nor destroyed in chemical reactions. The mass of any one element at the beginning of a reaction will equal the mass of that element at the end of the reaction. If we account for all reactants and products in a chemical reaction, the total mass will be the same at any point in time in any closed system.

In combustion, if you consider the mass of the fuel and atmospheric oxygen before combustion, this must be the same as the mass of unburned fuel, unused oxygen, plus the products of combustion (this leaves out nitrogen and other thermal ballast that are not part of the combustion reaction). This is a bit different than the balance of the mass of smoke exiting the compartment and the mass of air entering.

I posed a similar question to Dr. Stefan Svensson from Lund University concerning the difference in the volume of products of combustion discharged and air intake from a single opening with a bi-directional air track. I discussed Art’s question with Stefan to ensure that my answer was clear and as accurate as possible (while maintaining a practical context).

In actuality, I should have stated that mass and energy must be balanced. Application of the principle of conservation of mass and energy in practical fire dynamics is an estimate and it applies on the molecular level (i.e. molecular mass). Usually we look at the building as a system in which the principle of conservation of mass and energy works as a rough estimate. If you define the system as a large cube that contains the building, the cube becomes the system.

In considering mass balance in a compartment fire it is important to keep in mind that solid fuel in the compartment is undergoing pyrolysis; thermally decomposing into gas phase fuel. Some of the fuel burns producing a range of combustion products and some remains unburned. Smoke is comprised of air, products of combustion, and unburned pyrolizate.

As air, products of combustion, and pyrolizate are heated, the volume increases (but mass stays the same), cooler outside air flowing into the building is more dense (smaller volume, but the same mass). This results in approximate balance between of the mass of hot air and products of combustion exiting the building and the mass of cooler external air entering the building.

Density of Dry Air at 20o C: 1.205 kg/m3 (at Sea Level)

Density of Dry Air at 300o C: 0.616 kg/m3 (at Sea Level)

The implications of this difference in density is that if 1 m3 of hot air and products of combustion exit the building at 300o C, they will be replaced by approximately 0.5 m3 of cooler air (which will have the same mass as the exiting smoke and hot air. This differential will increase further if the temperature of the smoke is higher (resulting in lower density). It is important to note that the volume of air is not the same as the products of combustion and air that exit the compartment, but the mass is the same.

Pressure Differential and Flow

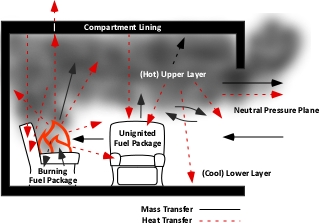

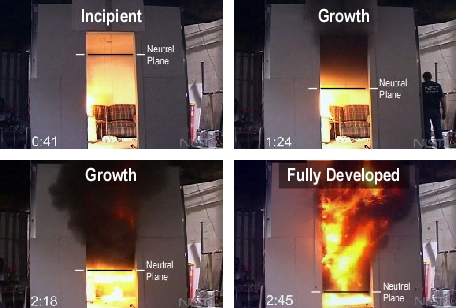

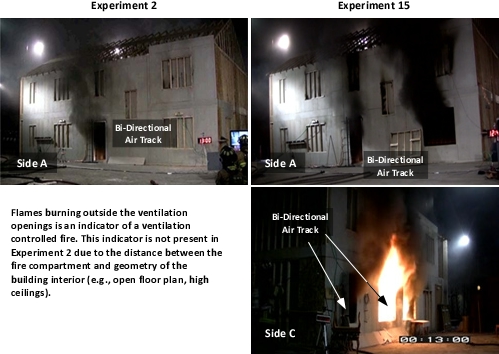

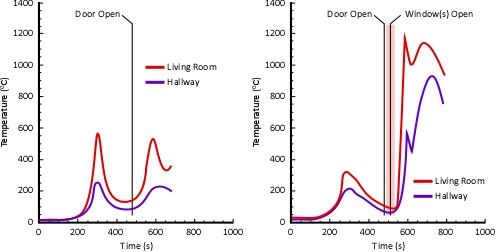

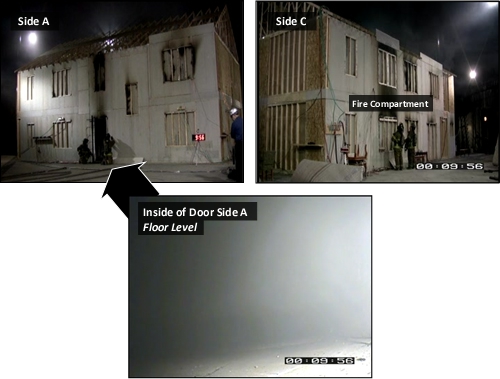

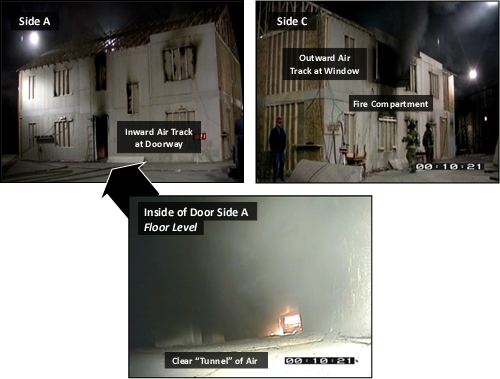

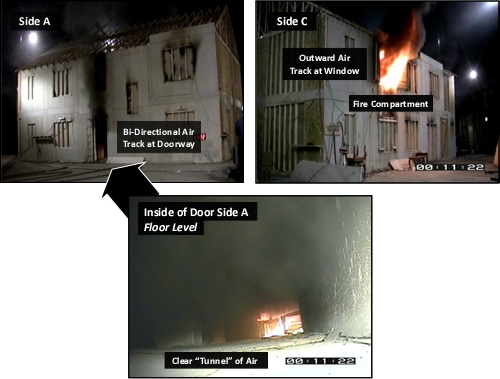

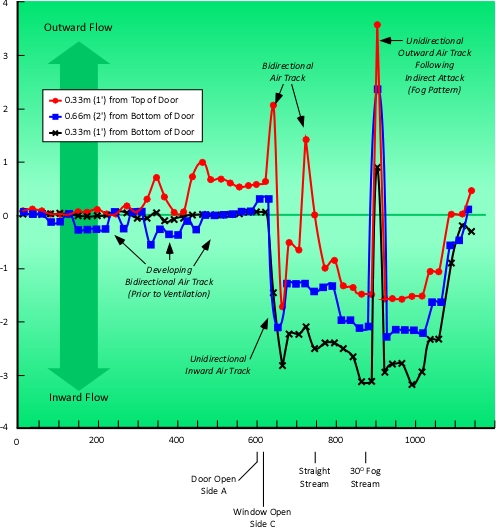

Smoke movement is due to both pressure and differences in density (gravity current). However, in general, the pressure differential between the interior of the building and the exterior is what causes smoke discharge. However, this pressure differential is not uniform and will be higher in the hot upper layer than in cooler air below (if a two layer environment exists inside the building). This is fairly simple to visualize when considering a single compartment. As shown in the following four photographs, hot smoke exits at the top of the door (above the neutral plane) and air enters at the bottom of the door (below the neutral plane). Movement of smoke in this case is the result of both the pressure resulting from increased temperature of the gases in the upper layer and the difference in density between the hot smoke (less dense) and the cooler air (more dense).

More Questions

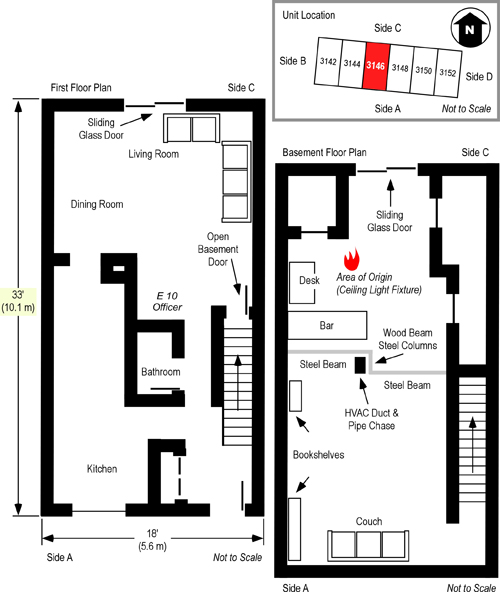

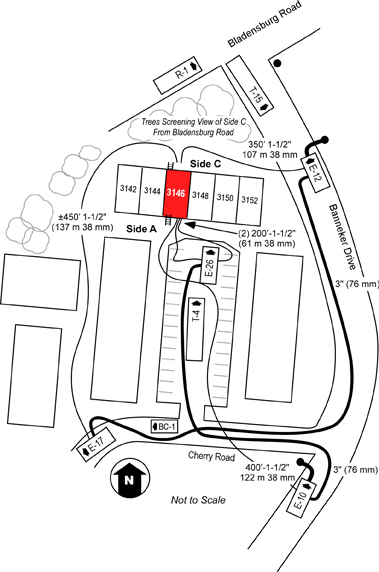

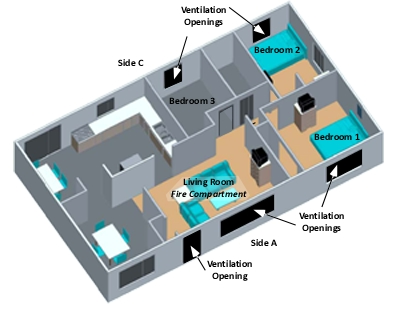

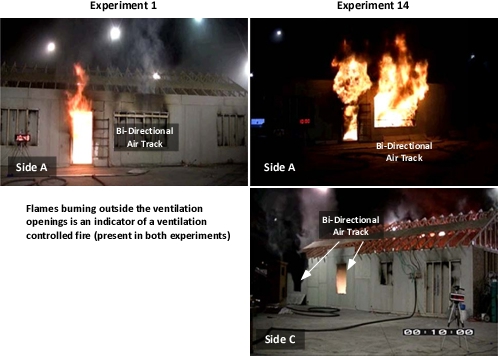

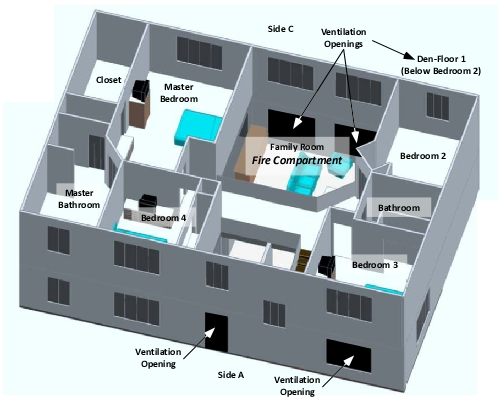

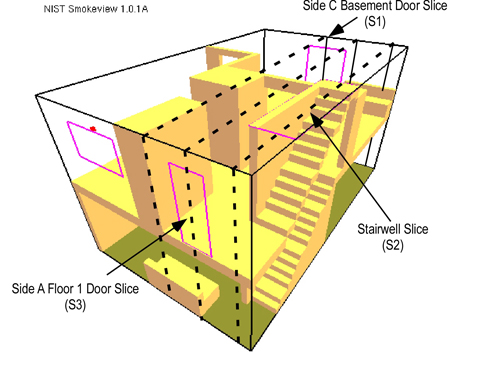

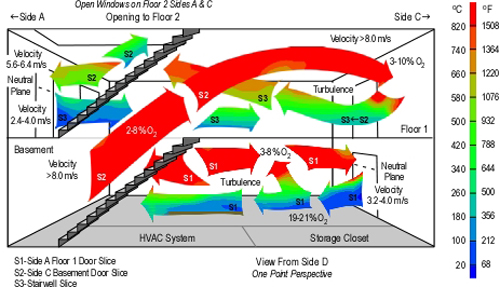

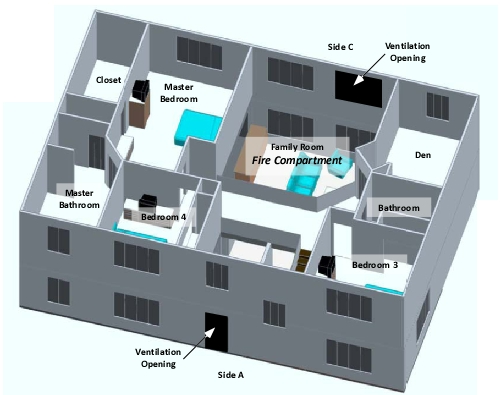

Mike Sullivan from Canada posed several related questions, focusing on a video included in the Large Vertical Vents are Good, But… post. Just to get everyone back up to speed on the video, this test was conducted by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) in Bensenville, IL. The building is a wood frame townhouse with a fire ignited on the first floor. The door on Floor 1, Side Alpha is closed and the window on Side 1, Alpha is open. The door to the second floor room where the open window is located is also open, providing a flow path between the window and the first floor fire.

Mike Asks: Although the Law of Conservation of Mass can be used to explain that for a mass of smoke to exit an equal amount of mass of oxygen must enter. But in reality is the mass of smoke inside the townhouse not an artificial mass—meaning—-typically all things in life are trying to reach an equilibrium. In this case I would think that the interior mass of smoke also elevates interior pressures and should continue exiting until an equilibrium with the exterior is met.

In the video the smoke does exit the window for quite a while. In this case if we were to discuss the Law of Conservation of Mass, would it be the mass of oxygen entering the lower part of the window that allows the smoke to exit OR with the fire burning in the living room is the mass of smoke being produced by the fire acting as a replacement for the mass of smoke exiting the window?

Both good questions! As previously discussed, smoke discharge (as well as movement on the interior) is the result of both differences in pressure and density. If considered simply from the perspective of higher pressure on the interior, smoke would discharge from the building until pressure equilibrium is reached (with the same pressure inside the building as outside). This is related to exchange of mass and energy, but only indirectly. If you opened a cylinder of compressed air, air would be discharged out of the cylinder into the atmosphere (no exchange). However, with a fire burning in the building, air must flow inward to sustain release of thermal energy, which in turn maintains (or increases) the temperature that causes the pressure increase.

Mike also had a question related to cooling of the upper layer with a solid stream, but that will be the focus of another post.

UL/NIST Video Series

Have a look at the seven part video series of Battalion Chief Derik Alkonis, LA County Fire Department; Steve Kerber, Underwriters Laboratories Firefighter Safety Research Institute, and Dan Madrzykowski, National Institute presenting on Fire Dynamics at the IAFF Redmond Firefighter Safety Symposium.

- Part 1-Introduction

- Part 2-The Fire Environment

- Part 3-Fire Dynamics

- Part 4-Case Studies

- Part 5-Fire Behavior Training

- Part 6-Live Fire Tests

- Part 7-Organizational Change

Upcoming Events

Taking Scientific Research to the Street, 2014 Fire Department Instructors Conference, April 9, 2014 at 13:30

3D Firefighting Workshop, Winkler, MB April 25 & 26, Call (204) 325-8151 to register or for more information

Note: Adapted from

Note: Adapted from