Jason Sowders recently wrote an post on the Fire Engineering in support 150 gpm (570 lpm) as the minimum flow rate for interior structural firefighting and the use of solid (or if not solid, at least straight) streams for interior fire attack. I commented on-line that many of the conclusions stated in Jason’s post was not supported by scientific evidence or the experience of many of the world’s fire services. Have a look at Jason’s post: Nozzle Selection: Are We Defeating the Enemy? and give some thought to what he has to day. What do you agree with, what do you disagree with, and why?

I commend Jason on presenting his perspective in a public forum. While I don’t agree with many of the things that he has to say, putting ideas in a public space allows discussion and argument (using this term in its most positive sense) to improve our knowledge and understanding. Today more than ever, we have access to a tremendous amount of information via the internet and print publications. Some of this information is correct and some is not. To make things even more complicated, some of it is based on commonly held belief resulting from observation of the world around us, that seems quite logical and some of it is based on science which is sound but may seem to conflict with our practical experience. How do we sort through these statements, claims, and arguments?

- Think about what you know?

- How do you know this?

- What are your assumptions and biases (this may be the most difficult question)?

- What resources are available to help you develop a deeper understanding?

Military Metaphor

Jason begins his post by asserting that warfighting involves precision, well thought out methods of attack and overwhelming force to obliterate the enemy. Both statements have an element of truth, but the military metaphor for structural firefighting while useful in some contexts has significant limitations. Consider the differences between a ground offensive in a war and a special operations mission to capture or kill a terrorist leader. Both have elements of precision and well thought out methods, but the later does not use overwhelming force to obliterate the enemy, but employs the force necessary to accomplish the task while minimizing collateral damage.

Jason states that we are in a war and that fire has already invaded our homes, ready to show itself in a very “hostile” manner. The major fallacy in the use of military action or warfare as a metaphor for firefighting is the tendency to anthropomorphize the fire, ascribing humanlike characteristics such as thought and intent. An uncontrolled fire is not alive, it is not hostile, and it is not trying to kill either firefighters or civilians it is simply a physical and chemical phenomena that presents a hazard to life and property in either the natural or built environment.

Chief Fire Officer Paul Young of the Devon & Somerset Fire & Rescue Service asked two important questions during a presentation at an Institution of Fire Engineers presentation several years ago: Are we participating in an individual struggle with a dangerous enemy? Or are we part of a disciplined, organized, and coordinated attack on an increasingly well understood chemical reaction?

These points do not diminish the hazards presented by the modern fire environment, but frame a fundamental difference in perspective about our work. One is dramatic, exciting, and focused to a greater extent on an emotional response (which is necessary, but not sufficient) and the other recognizes that our work while difficult, physical, and requiring emotional strength, must be based on integration of scientific evidence and experience developed in the field.

Heat Release Rate

Jason asserts that the heat release rate of today’s fuels is catching firefighters off guard and that they need to be treated as highly flammable fuels. While this is true to some extent, the term flammability generally refers to ease of ignition (e.g. flash point of liquids, ignition temperature, etc.) rather than heat of combustion (potential energy) or heat release rate (HRR). Jason’s statement that “heat makes more heat” is nonsense at face value in that heat (thermal energy in transit cannot multiply itself. Chemical potential energy in fuel can be transformed to thermal kinetic energy, but it can neither be created or destroyed (law of conservation of energy). However, if the point is that HRR does not (generally) increase in a linear manner, but frequently increases in an exponential manner, is generally correct.

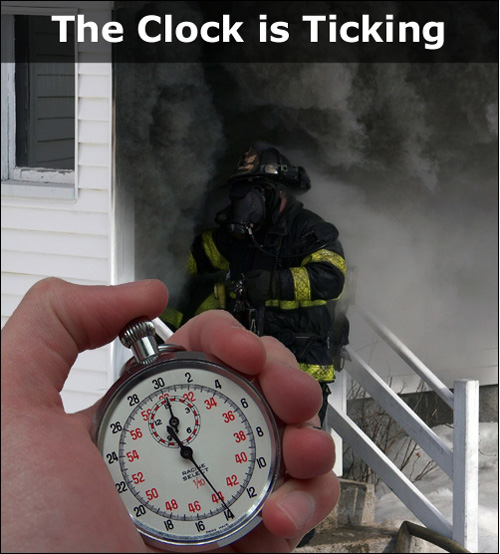

Understanding the concept of heat release rate is critical to understanding and recognizing the hazards presented in the fire environment as well as the capabilities of water as an extinguishing agent.

Flow Rate

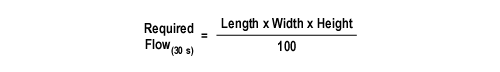

Jason asserts that flow rates below 150 gpm (768 lpm) are inadequate for interior structural firefighting without supporting this argument with specific evidence. While I agree that a 1-3/4” hoseline with a flow rate of 150 gpm (570 lpm) is a reasonable choice for interior structural firefighting, there are many fire service agencies around the world that are quite effective with much lower flow rates. How can this be? Context is critical and it is important to consider building characteristics, fuel loading, and tactical framework. That said, it is interesting that the New South Wales Fire Brigades in Australia (who has similar buildings and fuel loads to those found in North America) typically makes entry to residential fires with a flow rate that is five times lower than 150 gpm (570 lpm). This large fire brigade serving both the city of Sydney and smaller communities is effective in fire control while having a firefighter fatality rate that is considerably lower than the US fire service. This is likely due to a combination of factors, but their typical flow rate and use of 38 mm (1-1/2”) hoselines does not seem to have a negative impact on their fire suppression performance.

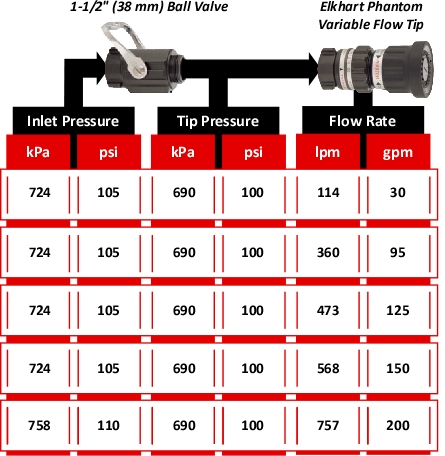

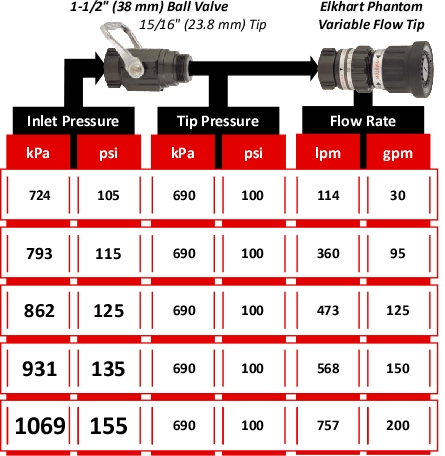

Jason provides an example of the effect of reducing line pressure on 200’ a 1-3/4” handline from 170 psi to 130 psi (to reduce nozzle reaction); stating that this would reduce the flow rate from 150 gpm (570 lpm) to 115 gpm (435 lpm) and that this would be “woefully inadequate and not a safe practice” as you would be simply containing the fire, not extinguishing it.

The first part of this argument has an element of truth. Reducing the line pressure on a handline reduces flow rate. However, depending on the type of nozzle, there may be other impacts as well. An automatic nozzle will maintain its design pressure with reduced flow rate (as long as the flow is within the nozzle’s flow range). If the nozzle is a standard combination nozzle with a designed nozzle pressure of 100 psi (689 kPa) as evidenced by the original 170 psi (1172 kPa) nozzle pressure in this example, reducing the line pressure not only reduces flow rate, but also increases droplet size and velocity of the stream; which further degrades performance. However, this leaves the question of what flow rate is “adequate” for structural firefighting. As with most questions, the answer is it depends.

Before starting a discussion of the adequacy of given flow rates, it is important to provide a bit of context (as this is not a debate just for the sake of argument, it is important for us to understand not only what we do, but why we do it).

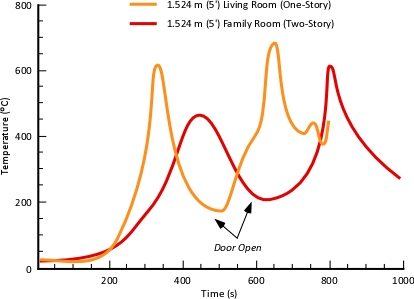

Jason states that a flow rate of 115 gpm (435 lpm) will is inadequate and unsafe and that it will only contain the fire and not extinguish it (without stating fire conditions). Consider the cooling capacity of 115 gpm (435 lpm); this flow rate has a theoretical cooling capacity of 18.87 MW (7.26 kg/s x 2.6 MJ/kg = 18.87 MW). Given that this cooling capacity cannot be achieved in a practical sense it may be reasonable to say that the efficiency of hand held fire streams varies considerably, but as a point of illustration, consider an efficiency of 50% (half of the water is vaporized to steam). In this case, the cooling capacity of 115 gpm (435 lpm) would be 9.43 MW. As a point of comparison, tests of a fully furnished modern living room conducted by Underwriters Laboratories resulted in a heat release rate of slightly less than 9 MW (Kerber, 2012) and could be readily controlled and extinguished with a flow rate lower than 150 gpm (570 lpm).

I have no argument with establishing a minimum flow rate for 1-3//4” handlines (and actually use 150 gpm as the standard for the agency where I serve as Fire Chief). However, not all fires require 150 gpm (768 lpm) and in other cases 150 gpm (570 lpm) is inadequate. Safety is not driven by flow rate, but by appropriate or inappropriate use of a given flow rate depending on conditions. At a minimum, the flow must at least meet the critical flow rate (minimum to extinguish the fire) and more likely should be somewhat higher to reduce the time to extinguishment. Drastically exceeding the critical flow rate has considerably less impact on time to achieve extinguishment, but has a significant impact on the total volume of water used (which in rural contexts can be limited and in any context results in unnecessary fire control damage). If this resulted in increased firefighter safety, this might be a reasonable tradeoff, but I have not seen evidence that this is the case.

Fire Streams

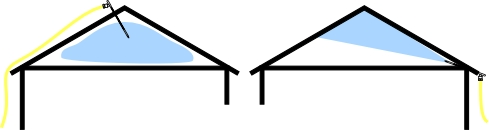

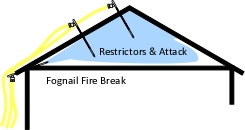

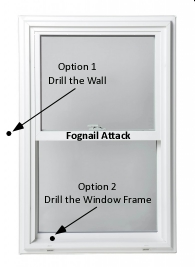

Jason’s use of Lloyd Layman’s work as an illustration of how water fog is used in firefighting is misleading. Indirect attack is only one way in which a combination nozzle can be used in structural firefighting. Jason is correct in that indirect attack involves production of a large volume of steam to cool and inert a fire compartment or compartments and that this method of fire attack should not be used in compartments occupied by firefighters (or savable victims).

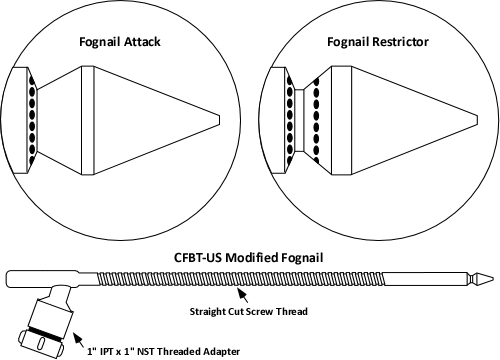

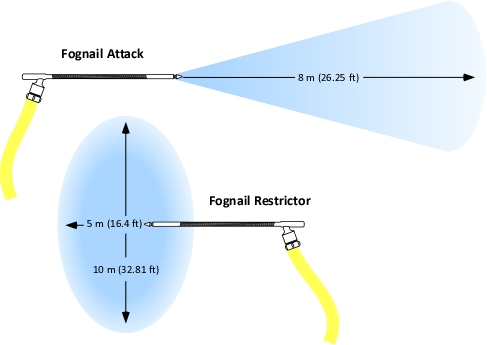

Jason states “the fog stream has a much larger surface ratio and little if any of the broken stream makes contact with solid surfaces or fuel source. Remember, our goal is to apply water to the fuel source, not to just cool off the thermal layer.” While, a fog stream has a much larger surface area than a straight or solid stream, the remainder of this statement presents a number of problems.

First it is important to distinguish between a fog stream and a broken stream (which are quite different). A fog stream has much smaller droplets (which appears to be Jason’s point) while a broken stream (such as that produced by a Bresnan distributor) has much larger droplets.

Jason’s second point that little if any of the water makes contact with solid surfaces of the burning fuel is in direct conflict with his claim that the fog pattern produces a large volume of steam to fill the compartment (as in Layman’s indirect attack). Due to the substantial energy required to heat water to its boiling point (specific heat) and vaporize it into steam (latent heat of vaporization) and the relatively low specific heat of the hot gases; water vaporized in the upper layer actually reduces the total volume of hot gases and steam in the compartment. Water vaporized on hot surfaces does not take appreciable energy from the hot gases and the volume of steam produced is added to the total volume of the upper layer, resulting in the lowering of the bottom of the layer and making conditions less tenable. For a more detailed discussion of gas cooling see my prior post Gas Cooling, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, and Part 5. If in fact the water is not reaching hot surfaces, it would not have the effect that Jason describes. If it does reach the surfaces, resulting in the effect described, a fog pattern actually does cool hot surfaces and burning fuel. The fact of the matter is somewhere between these two extremes. Effective use of a combination nozzle allows for cooling of gases when this is the goal and cooling of hot surfaces and burning fuel when position allows direct attack.

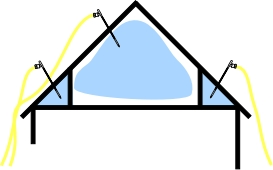

I agree with Jason’s third point, that the goal is to “apply water to the fuel source, not just to cool off the thermal layer” [emphasis added]. However, if faced with a shielded fire and direct attack is not possible from the point of entry, it is necessary to cool the hot upper layer to reduce potential for ignition of the hot smoke (fuel) and reduce the thermal insult to the firefighters below. This requires a stream that is effective at cooling the gases (rather than only or primarily surfaces). Once it is possible to apply water directly onto the burning fuel, this is critical as gas cooling is not an extinguishing technique, but simply a way to more safely gain access to the seat of the fire. For additional discussion of shielded fires and application of gas cooling see my previous post Shielded Fires and Part 2.

It is indisputable that a fog pattern can be used to create a negative pressure at an opening such as a window or door to aid in ventilation and that a solid stream held in a stationary position and projected through the same opening will create less of a negative pressure and have less impact on ventilation. However, it is incorrect to state that the fog stream will always have this effect and thus will have a negative impact if used for interior firefighting. Development of the increased air movement described requires that the stream be positioned in an opening to create a negative pressure, thus influencing air flow. Intermittent operation on the interior does not produce the same result.

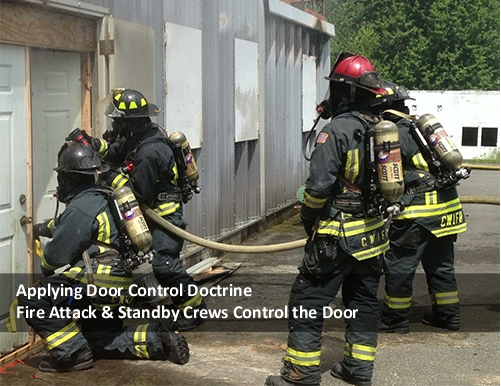

Jason Sowders states “Let’s leave ventilation to the truck companies. Our main focus for the initial stretch should be extinguishment.” I have no argument that the main focus of the first line stretched should be confinement and extinguishment of the fire. However, engine companies have a significant impact on ventilation (and are an essential part of this essential tactic) in that all openings created in the building (including the door that the line was advanced through) are ventilation openings. For more on the entry point as ventilation, see my earlier post Influence of Ventilation in Residential Structures: Tactical Implications Part 2 and the last several posts on door control; Close the Door! Were You Born in a Barn? and Developing Door Control Doctrine.

Jason also states “We have been fooled for many years believing that a curtain of water between you and the fire is protection. What is occurring is that you are pushing heat, fire, smoke, and other products of combustion out in front of you.”

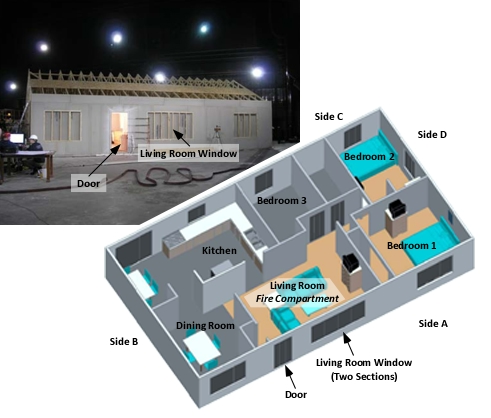

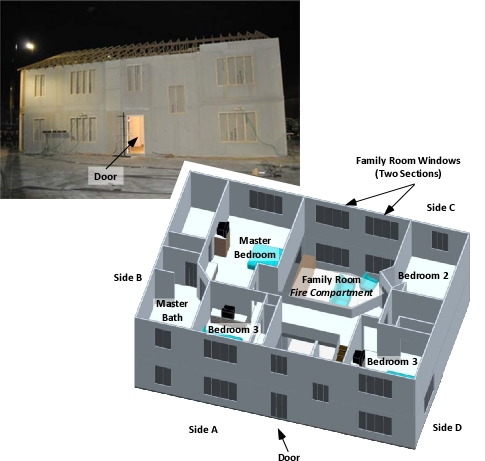

There are several interesting issues with these claims. First, if a fog pattern did not provide effective protection from radiant heat, fog streams would be ineffective protection when dealing with exterior flammable gas fires. However, this is not the issue here. As demonstrated in tests conducted by Underwriters Laboratories (UL) on Horizontal (Kerber, 2011) and Vertical Ventilation (Kerber, in press) as well as additional tests conducted by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and the Fire Department of the City of New York (FDNY) (Healey, Madrzykowski, Kerber, & Ceriello, 2013), water does not push fire (for more information see the UL Report and On-Line Training Program Impact of Ventilation on Fire Behavior in Legacy and Contemporary Residential Construction. When a stream is operated continuously as in a combination attack where the stream (fog, straight, or solid) is rotated to cover the ceiling, walls, and floor and water is vaporized on contact with hot surfaces and burning fuel, steam is produced and the air flow developed by the stream aids in pushing these gases away from the nozzle and hopefully, towards an exhaust opening (half of the ventilation equation). Coordination of fire attack and ventilation is always important, but in this case ventilation in front of the hoseline is critical to safe and effective extinguishment. This is true regardless of the type of nozzle and stream used.

Jason cites the disruption of the hot upper layer in the fire environment as a problem presented by application of water fog into the hot gases. He further asserts that a straight or solid stream will provide a more rapid knockdown by reaching the seat of the fire without premature conversion to steam or being carried away by convection currents. As with many of the other arguments in Jason’s post, there is an element of truth here, but not the entire story.

As discussed above, application of water in a manner to produce steam on contact with hot surfaces will in fact disrupt thermal layering (regardless of the type of stream), this has given rise to empirical (observed) evidence that application of water fog into the hot upper layer has adverse consequences. However, if applied at a flow rate and/or duration that results in vaporization in the hot upper layer, conditions improve. Penetration is often cited as an advantage of straight or solid streams. This is true, provided that the stream can be directly applied to the burning fuel. Reach of the stream becomes particularly important when working in large compartments that are well involved. In many cases, firefighters must gain access to the fire compartment prior to being able to make a direct attack on burning fuel and thus may have need first cool the hot gas layer on approach and then make a direct attack. These two tasks may be efficiently accomplished using a combination nozzle to cool hot gases with pulsed application of water fog and a straight stream for direct attack.

Jason emphasizes that solid stream nozzles produce a superior stream in comparison to that produced by a combination nozzle set on a straight stream. The primary rationale stated in this argument is that the stream is denser and droplets produced when the solid stream is deflected off the ceiling or walls are larger and have sufficient mass to reach the burning fuel without being vaporized in the hot gases or carried away by convection. As with several other of Jason’s arguments, this has an element of truth. Larger droplets are effective for direct attack due to their mass and smaller surface area, increasing the amount of water reaching the burning fuel. The effects of convection on a straight stream from a combination nozzle are far less pronounced in a compartment than they are when attempting a defensive direct attack on a large fire with a significant convection column.

Most Fire Departments

Jason asserts that “Most fire departments throughout the country are aware of the harmful effects of fog application and are teaching their recruits to use straight stream water application for interior structural firefighting”. I am uncertain if most fire departments are teaching that only straight or solid streams should be used for interior firefighting operations. However, I would dispute that fog application is “harmful”. There are potentially harmful effects of inappropriate water application regardless of the type of stream. Firefighters must understand water as an extinguishing agent and develop mastery in the use of their primary weapon (to use the military metaphor), the nozzle. Firefighters today are more aware of the need to cool hot smoke (fuel) in the upper layer, it is essential to understand the capabilities and limitations of each type of fire stream

Constant Change

Jason concludes with the statement “We must be ready for battle with effective hoseline selection, nozzle selection, and flow rates…. It is our duty to be proactive when it comes to the constant changes our profession brings.” I agree completely! However, our strategies, tactics, and doctrine must be evidence based, must have a sound theoretical foundation and be supported by both scientific research and practical experience. Unfortunately, our profession continues to struggles to integrate these elements and is saddled with conclusions based on experience without understanding. Theory and scientific research does not trump experience, neither does experience trump scientific knowledge. Both are essential!

The issues of flow rate and stream selection are not one sided, there is evidence for the effectiveness of both water fog and solid stream application for control of fires in today’s fire environment. It is easy to examine the evidence and choose the facts that support our preconceived ideas (regardless of your perspective). It is much more difficult to objectively evaluate the evidence and determine what conclusions are actually supported. We must continue to ask why and question our assumptions!

Ed Hartin, MS, EFO, MIFireE, CFO

References

Healey, G., Madrzykowski, D., Kerber, S., & Ceriello, J. (2013). Scientific research for the development of more effective tactics; Governors Island experiments July 2012 [PowerPoint]. Gaithersburg, MD: National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST).

Kerber, S. (2011). Impact of ventilation on fire behavior in legacy and contemporary residential construction. Retrieved July 16, 2011 from http://www.ul.com/global/documents/offerings/industries/buildingmaterials/fireservice/ventilation/DHS%202008%20Grant%20Report%20Final.pdf

Kerber, S. (2012). Analysis of changing residential fire dynamics and its implications on firefighter operational timeframes. Retrieved June 26, 2013 from http://www.ul.com/global/documents/newscience/whitepapers/firesafety/FS_Analysis%20of%20Changing%20Residential%20Fire%20Dynamics%20and%20Its%20Implications_10-12.pdf

Sowders, J. (2013) Nozzle Selection: Are We Defeating the Enemy? Retrieved June 26, 2013 from http://www.fireengineering.com/articles/2013/06/nozzle-selection–are-defeating-the-enemy-.html?sponsored=firedynamics