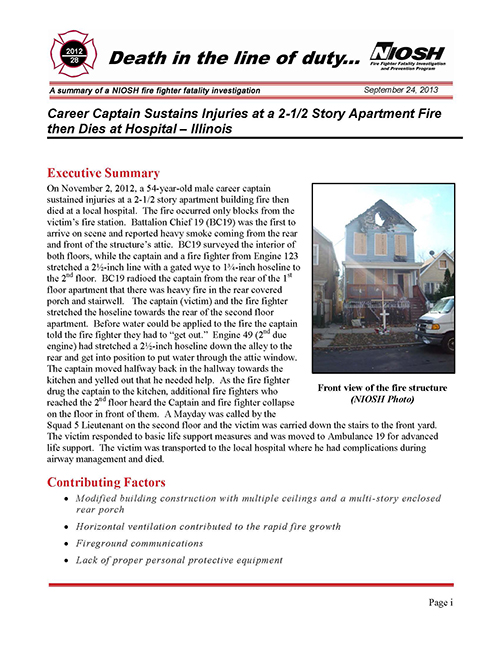

NIOSH Report 2012-28

Thought & Observations

Wednesday, November 27th, 2013

After reading National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) Death in the line of duty…2012-28, I was left scratching my head. For many years I have been a supporter of the Firefighter Fatality Investigation and Prevention Program and have served as an expert reviewer for several reports involving fatalities resulting from extreme fire behavior. As a friendly critic I have encouraged the NIOSH staff to improve their investigation and analysis of fire behavior related fatalities. Over the last several years there has been considerable improvement However, this latest report leaves a great deal to be desired. That said, there are a number of important lessons that can be drawn from this incident.

Discussion of Fire Behavior

The Fire Behavior section of the report identified the attic as the origin of the fire and that the fire burning in the attic was ventilation limited. The report also identified that the enclosed rear porch was substantially involved. However, the report failed to discuss how the fire may have extended from the attic to the lower area of the porch (other than a statement that the BC notices “fire raining down in the enclosed porch area”.

The report correctly described the influence of the addition of air to a ventilation limited fire; increased heat release rate and potential to transition through flashover to a fully developed stage. However, the report failed to clearly articulate that there are two sides to the ventilation equation, air in and hot smoke and fire gases out. Flow path is critical to fire development and extension, and in this incident was likely one of the most significant factors in creating untenable conditions in the 2nd floor hallway.

It would have been useful to examine how the changes in ventilation resulting from opening of doors at the first floor level, existing openings in the attic (windows at the front and rear), opening of the door at the 2nd floor to extend the hoseline, and failure of the rear door may have influenced the flow path. While, the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) modeling of this incident will shed considerable light on this subject, the physical evidence present at the fire scene could have informed discussion of flow path in the report.

Recommendation #1 states “Fire departments should ensure that fireground operations are coordinated with consideration given to the effects of horizontal ventilation on ventilation-limited fires”. This is a reasonable recommendation, but fails to speak to the importance of understanding flow path and the thermal effects of operating in the flow path downstream from the fire. In addition, while speaking to the importance of coordination, the report neglects to define exactly what that means; water on the fire concurrent with or prior to performing tactical ventilation.

Failure of the rear door established a flow path through the narrow, question mark shaped hallway and kitchen to the front stairway. Given the narrow width of this hall and its complex configuration, it is likely that there would be considerable mixing of hot smoke (fuel) and air providing conditions necessary for combustion. The dimensions of the space may also have influenced the velocity of the hot gases, increasing convective heat transfer.

The report did not speak to conditions initially observed in the kitchen and hallway or observed changes in conditions by members of other companies or the Engine 123 firefighter, prior to Captain Johnson’s collapse.

Things to Think About: Conditions on floor 2 were quite tenable prior to failure of the 2nd floor rear door, but changed extremely quickly in the hallway when the door failed. It is important to consider potential changes in flow path resulting from tactical operations and fire effects. It is unclear if the crews working on the 2nd floor were aware of the extent or level of the fire in the rear porches (having observed conditions indicating an attic fire on approach). The BC addressed the fire in the rear, but the it is uncertain if the line stretched to the back of the building was in operation before door failed or if application through the attic window would have significantly impacted the fire in the lower areas of the porch.

Structure

The section of the report addressing the Structure provided a reasonably good overview of the construction of this building and identified that the 2nd floor ceiling had multiple layers. However, there was no discussion of what influence these multiple layers may have had (e.g., reducing the thermal signature of the fire burning above). One significant element missing from discussion of the structure was the open access between the rear porch and the attic that allowed ready extension of fire to the rear porches.

The report also failed to discuss the type of door between the 2nd floor living area and the rear porch, other than to mention in passing that it was metal. Closed doors frequently provide a reasonable barrier to fire spread, but in this case, the door failed following an undetermined period of fire exposure. This was likely a significant factor in changing the flow path and creation of untenable conditions on the 2nd floor.

Things to Think About: Closed doors can provide a significant fire barrier in the short term. However, it would be useful to examine door performance in greater depth to understand what happened in this incident.

Training and Experience

The section of the report addressing training and experience is exhaustive, providing an overview of state training requirements implemented in 2010 (well after the Captain would have attended recruit training). It was unclear if these requirements were implemented on a retroactive basis. The number of hours of training for various personnel involved in the incident were provided, but with little specificity as to content of that training.

These observations are not intended to infer that the training of the members involved was or may have been inadequate, but simply that if NIOSH is investigating a fire behavior related incident, it would be useful to speak to training focused on fire behavior, rather than a generic discussion of training.

It was also interesting to note that while the report spoke well of the Chicago Fire Department training program, it failed to mention that the CFD has been heavily involved in fire dynamics research with both NIST and Underwriters Laboratories (UL) for many years.

Things to Think About: If you are reading this, you likely are plugged into current research in fire dynamics and tactical operations. Share the knowledge and build a strong connection between theory and practical application on the fireground.

Other Observations

While the floor plan of the 2nd floor is useful in understanding the layout of that space, it does not provide a good basis to visualize the flow paths and changes in flow paths that influenced the tragic outcome of this incident. Providing a simple three dimensional drawing with ventilation openings would have significantly increased the clarity of the information provided.

Things to Think About: Don’t be a passive user of NIOSH reports. For a host of reasons, NIOSH does not include the names of Firefighters who have died in the line of duty, the agency they worked for, or the location of the incident (other than the state). However, this information is readily available and can provide additional information to help you understand the incident. In this case accessing the address of this incident (2315 W 50th Place, Chicago) allows the use of Google Maps satellite photos and street view to gain a better perspective of the exterior layout of the building and configuration of openings.

Final Thoughts

The NIOSH Firefighter Fatality Investigation and Prevention Program is an important and valuable resource to the fire service. Developing an understanding of causal factors related to firefighter fatalities is an important element in extending our knowledge and reducing the potential for future line of duty deaths. Firefighters often observe that NIOSH reports simply say the same thing over and over again. To some extent this is true, likely because Firefighters continue to die from the same things over and over again.

The fire service across the United States is making progress towards developing improved understanding of fire dynamics and the influence of tactical operations on fire behavior. This is in no small part due to the efforts of the UL Firefighter Safety Research Institute, NIST, and agencies such as the Chicago Fire Department and Fire Department of the City of New York (FDNY). However, we need to look closely at near miss incidents, those involving injury, and fatalities resulting from rapid fire progression and seek to develop a deeper understanding of the contributing and causal factors. The NIOSH Firefighter Fatality Investigation and Prevention Program can be a tremendous asset in this process, but more work needs to be done.

What’s Next

I just spent the last two days at UL’s Large Fire Lab for the latest round of Attic Fire Tests and will be headed to Lima, Peru the first week of December. While on the road I will be working on my thoughts and observations related to attic fire tactics. The simple answer is that there is no single answer, but these recent tests presented a few surprises and have given me a great deal to think about.

Ed Hartin, MS, EFO, MIFireE, CFO