FAQ-Fire Attack Questions Part 3

Saturday, April 27th, 2013Amazing!

Thursday morning saw a sea change in perspectives on fire behavior in the United States! Over 2500 people were in the big room at FDIC to hear BC George Healey (FDNY), Dan Madryzkowski (NIST), Steve Kerber (UL), and LT John Ceriello (FDNY) talk about fire research conducted on Governors Island in New York.

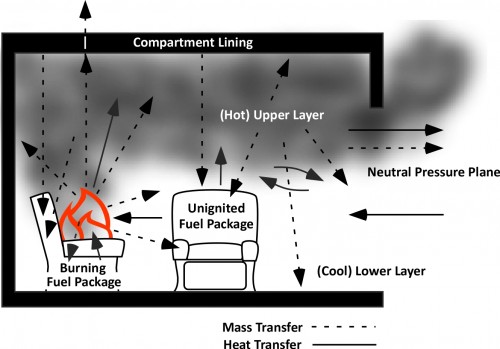

This excellent presentation emphasized the importance of understanding fire behavior and the influence of flow path and provided several key tactical lessons, including:

- Importance of control, coordination, and communication between crews performing fire attack and those performing tactical ventilation

- The effectiveness of anti-ventilation such as closing the door (even partially) on slowing fire development

- Effectiveness of water quickly applied into the fire compartment (from any location, but in particular from the exterior) in slowing fire progression

- The demonstrated fact that flow path influences fire spread and not application of water. You can’t push fire with water applied into the fire compartment.

- Importance of cooling the hot smoke (fuel) in the upper layer

Several years ago, who would have thought that a presentation on fire dynamics and research would have drawn this number of people to a presentation at FDIC. Kudos to FDNY, NIST, and UL for their ongoing work in developing an improved understanding of fire dynamics and firefighter safety.

FAQ (Fire Attack Questions) Continued

I had the opportunity to visit with Captain Mike Sullivan with the Mississauga Ontario Fire Department while at FDIC and we are continuing our dialog with another series of questions related to the characteristics of water fog and its use of a fog pattern for self-protection when faced with rapid fire progression in a structure fire.

The next three questions deal with using a fog stream for protection. In the IFSTA Essentials of Firefighting 5th edition it states that “wide fog patterns can also protect firefighters from radiant heat”, however in the IFSTA Essentials of Firefighting 3rd edition it states “In the past, water curtain broken stream nozzles were commonly used for exposure protection. However, research has indicated that these nozzles are only effective if the water is sprayed directly against the exposure being protected”. This tells me that fog patterns cannot protect from radiant heat.

Another question for which the answer is “it depends”. Both statements are correct (in context). Water droplets reduce radiant heat by absorbing energy and scattering the radiant energy. The effectiveness of these mechanisms depends on droplet size, wavelength of the radiation, geometric dimensions of the water spray, and density of the fog pattern. To put this in context, firefighters use a water spray for protection when approaching a flammable gas fire. In this context, the high density of the spray in proximity of the nozzle is quite effective. In contrast, application of a water spray between a fire and exposure is likely to be much less dense, and thus less effective in protecting the exposure than simply applying water to the exposure to keep its temperature <100o C.

In the past there was a belief (which some still believe) that if you find yourself in a bad situation in a house fire you can simply switch to a wide fog and it develops an “umbrella of protection from the heat and fire”. I believe this to be false. What I do think has happened in the past is that firefighters have found themselves in a room with extreme rollover or even had pockets of unburned gas igniting around them. When they used this technique they didn’t protect themselves with an umbrella of fog protection but they cooled the smoke layer and made the situation better.

This also is an interesting question, there are incidents where firefighters have opened the nozzle when caught in rapid fire progression and have survived (not necessarily uninjured), likely due to the cooling effects of the water spray. However, I would agree that this does not provide “an umbrella of protection” like a force field that provides complete protection. The benefit is likely by cooling of the hot gases above and potentially controlling some of the flaming combustion in the immediate area. However, as continuous application will likely not only cool the hot upper layer, but also generate a tremendous amount of steam on contact with compartment linings, the environment will not be tenable in the long term. However, this environment is likely more survivable than post-flashover, fully developed fire conditions.

Much the same as in driving or riding in fire apparatus, the best way to avoid death and injury in a crash is to not crash in the first place. If firefighters recognize worsening fire conditions, they should cool the upper layer to mitigate the hazards presented, if this is ineffective, withdrawing while continuing to cool the upper layer is an essential response.

My last comment on this; and this is where I am not really sure. If you are in a situation where you need to back out quickly, would it work to use a fog stream to push the heat away as you are reversing out of the structure? You would only do this for a short time while you retreat.

If you cannot put water on the fire to achieve control (shielded fire) or the heat release rate (HRR) of the fire exceeds the cooling capacity of your stream you are in a losing position. When faced with rapidly deteriorating thermal conditions, it is essential to cool the upper layer. It is important to note that cooling, not simply “pushing the heat away” is what needs to happen in this situation. This action reduces heat flux from both convective and radiant transfer. Adequate water must be applied to accomplish this task, as temperature increases so too does the water required. Long pulses provide a starting point, but the pulses need to be long enough to deliver the required water. If needed, flow could be continuous or near continuous while the crew withdraws. In much the same manner a crew working with a solid stream nozzle would operate the nozzle in a continuous or near continuous manner and rotate the stream to provide some cooling to the upper layer while withdrawing.

There are those who believe that you can use a fog stream to protect yourself in a house fire by pushing the heat away from you as you advance on the fire. I believe you can push heat away from you and it happens in 2 distinct ways, the wide fog with the entrained air is literally pushing the heat away from you and you have now created high pressure in an area that was low pressure (typically you are near an open door) so you have effectively changed the flow path. Having said this, I feel the benefits are short lived. With this fog pattern you will also be creating a lot of steam which will continue expanding until it’s temperature reaches equilibrium with the rest of the fire compartment (expansion could be as high as 4000 times). With all this pushing and expansion you are now creating high pressure in an area down stream from you that had previously been a low pressure area. As we know, everything is trying to move from high to low pressure, now the low pressure area is directly behind the nozzle. Now you are in a situation where not only is the heat coming back behind the nozzle but there is an enormous amount of steam being created and heading your way. The confusion here is most likely with the techniques we use when practicing for gas fires, we do this outside where there is an endless amount of space to push the heat away (I read this part in a good article in Fire Engineering).

The impact of continuous application of a fog stream (or any stream for that matter) as you advance is dependent on a number of factors, principal among which are the flow path and where steam is produced (in the hot gas layer versus on contact with surfaces). Continuous application is likely to result in vaporization of a significant amount of water on contact with surfaces; this will result in addition of steam to the hot upper layer without corresponding contraction of the hot gases that results from vaporization of water while it is in the gases. Without ventilation in front of the fog stream (or any stream for that matter), this can result in a reduction in tenability. However, when ventilation in front of the stream is provided, a combination attack (using a fog pattern, straight, or solid stream) can be quite effective for fully developed fire conditions.

I was hoping you could elaborate on the term “painting”. It is defined as a “gentle application of water to cool without excess steam production”. The hard part as a firefighter is the word “gentle” as this word doesn’t register in firefighter lingo. I can see this during overhaul but was hoping you could elaborate.

The way that I typically explain the concept of “gentle” is using a fire in a small trash can or other incipient fire inside of a building. If you use a hoseline to extinguish this fire, it is unlikely that you will need a high flow rate or application of the stream with the bail of the nozzle fully open. It would be appropriate to simply open the nozzle slightly on a straight stream and apply a small amount of water to the burning fuel.

Surface cooling can be done using a vigorous application from a distance when faced with a well involved compartment. In this situation, the reach of the stream is appropriately used to extinguish the fire and cool hot surfaces from a distance to minimize thermal insult to firefighters while quickly achieving control. However when faced with hot and pyrolizing compartment linings or contents, it may be useful or necessary to cool these surfaces from closer proximity. In this case applying water with force will result in much of the water bouncing off the surfaces and ending up on the floor. Painting involves using a straight stream or narrow fog pattern with the nozzle gated back to provide a gentle application resulting in a thin layer of water on the hot surface. As you note, this is most commonly used during overhaul, but could be used anytime that there is a need to cool hot, pyrolizing, but unignited surfaces.

Next week Mike and I will conclude this series of FAQ with a look at pyrolysis and flow path.