The Door Control Debate Continues

Monday, July 7th, 2014

Fire Rescue magazine Editor in Chief Tim Sendelbach recently raised a number of questions related to door control in his recent on-line article, Becoming Better Informed on the Fireground(2014). This article, has generated a fair bit of on-line discussion around the following issue: Which is a better tactic to provide a more tenable environment for the occupants; closing the door to limit inward air flow and reducing heat release rate (HRR) or leaving it open to reduce smoke logging of the space and provide an inward flow of air to aid in occupant survivability?

The debate may be broken down into a number of more specific question that frame the larger issue in a simpler way (or a more complex way, depending on your perspective):

- Will reducing the oxygen concentration to limit the HRR also have a negative effect on survivability of occupants due to the oxygen deficient atmosphere?

- Which results in a more toxic atmosphere, closing the door or leaving the door open?

- Which presents the larger and most significant threat, fire development or the toxicity of the atmosphere?

As always there are no simple answers to these questions. The answers depend on a number of variables that are unlikely to be known during fireground operations. However, we cannot be paralyzed by this complexity as strategic and tactical decisions must be made in a timely manner.

Place the Questions in Context

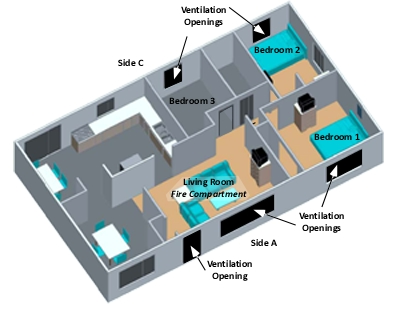

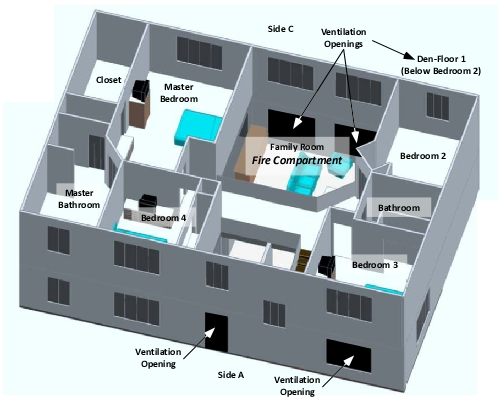

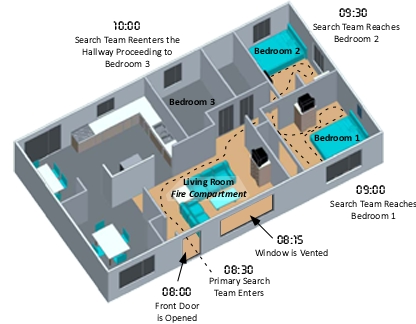

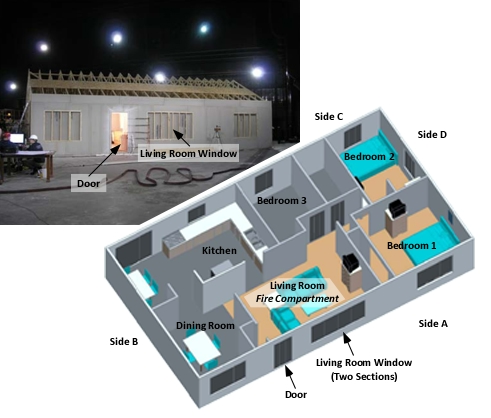

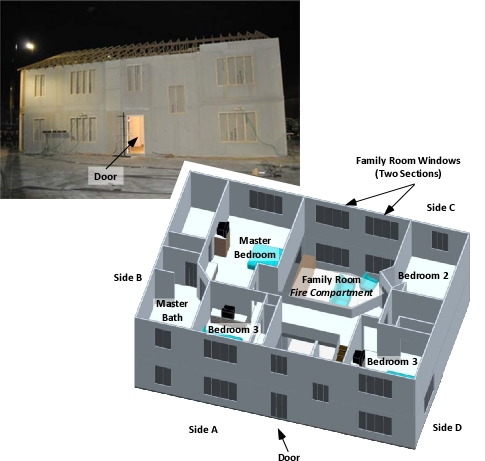

In order to frame the questions, consider a fire scenario which could result in serious injury or fatality to one or more building occupants: A fire in a one story, three bedroom, single family dwelling, occurring in the late evening or early morning hours, resulting from ignition of bedding as the result of contact with a cigarette (USFA, 2013a, 2013b). Bedroom 1 is the room of origin and has an open door to a hallway leading to the remainder of the house. Bedroom 2 is immediately adjacent to Bedroom 1 and has a closed door. Bedroom 3 is slightly further away from Bedroom 1 (than Bedroom 2) and has an open door. The home has functioning smoke alarms and the occupant of Bedroom 3 was alerted to the fire by alarm activation and was able to escape. The occupants of Bedrooms 1 and 2 were not alerted by the smoke alarm and remained in their respective bedrooms.

Scenario 1: The occupant of Bedroom 3 exited the home, leaving the front door open. Bedroom windows are closed and remain intact. These conditions remain constant until the arrival of the first fire company.

Scenario 2: The occupant of Bedroom 3 exited the home, closing the front door. Bedroom windows are closed and remain intact. These conditions remain constant until the arrival of the first fire company.

In both of these scenarios, companies arrive to find one occupant who has exited the building, and two occupants reported with a last known location in Bedrooms 1 and 2.

Fire Development in Scenario 1

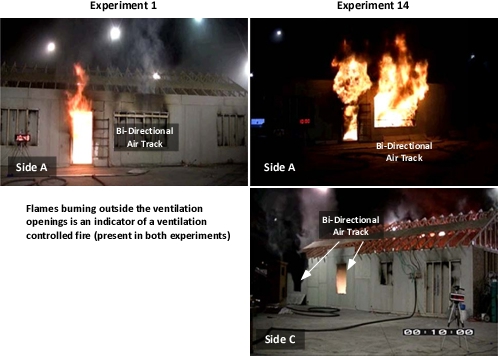

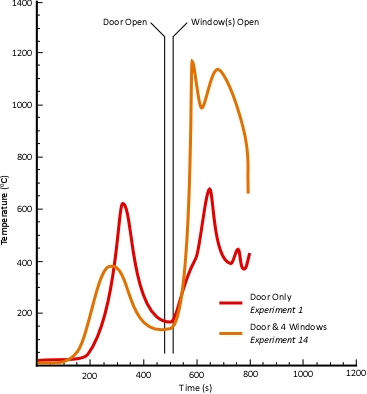

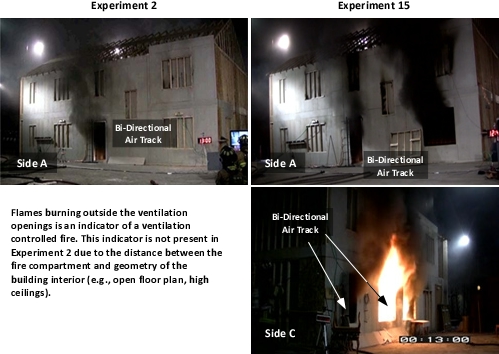

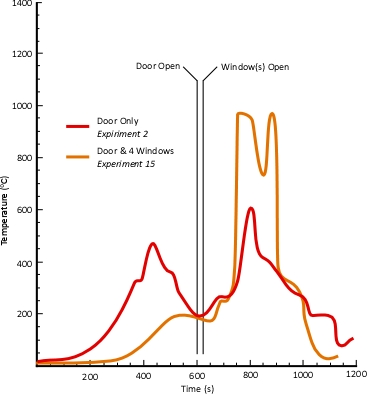

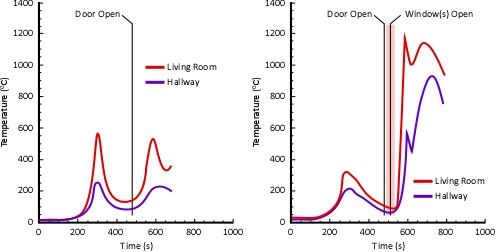

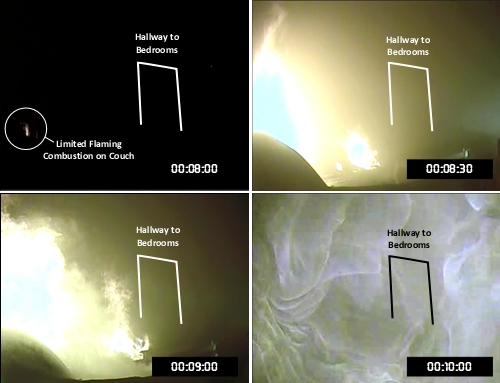

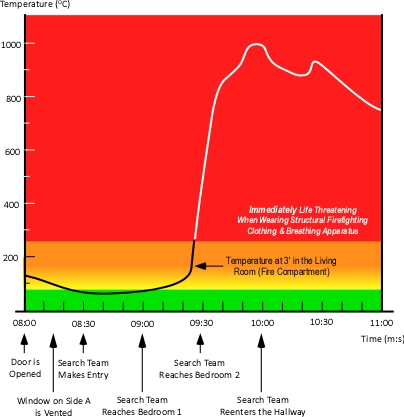

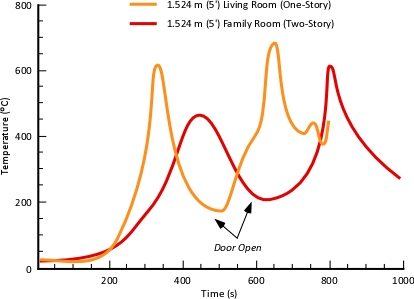

In this scenario, the open bedroom door provides an adequate supply of oxygen to allow the fire to quickly progress from the incipient to the growth stage and transition through flashover. This results in untenable conditions in the fire compartment. A bi-directional air track exists in the flow path between the front door and the fire. Hot gases will exit the fire compartment and flow towards the front door at the upper level. Prior to flashover the fire will become ventilation limited and will continue in this state as the fire becomes fully developed in Bedroom 1 and flames extend into the hallway.

Conditions will vary considerably throughout the dwelling depending on location and height above the floor. Close to the fire, the hot upper layer will be well defined, but radiant heat flux at floor level will likely make conditions thermally untenable. Smoke production will be substantial and will likely fill any areas open to the fire (e.g., living spaces open to the hallway and bedroom with an open door). As distance from the fire increases, smoke will cool somewhat and smoke will be present in both the hot upper layer and the cooler layer below. Air moving from the open front door to the fire, will provide some cooling and a higher oxygen concentration along the flow path. However, continued fire development will result in increased smoke production and will likely overwhelm the ventilation provided by the open front door, causing increased velocity of smoke discharge and lowering of the upper layer. Flames will extend down the hallway and towards the front door, increasing radiant heat flux, pyrolizing fuel, and will likely result in a growth stage fire along the flow path.

Conditions at the lower levels remote from the fire may remain tenable for some time and even with close proximity to the fire compartment, Bedroom 2 with the closed door is also likely to provide tenable conditions for some time.

Fire Development in Scenario 2

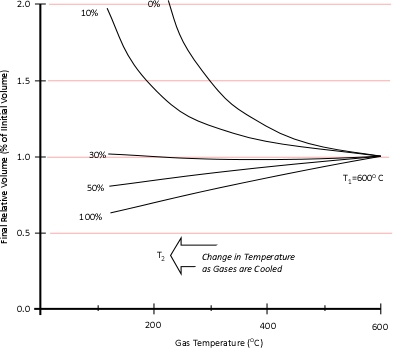

In Scenario 2, the basic conditions at the start of the fire are the same. However, in this case, the exiting occupant closes the front door. Initially, there will be little difference in fire development as oxygen from throughout interconnected compartments will sustain fire growth. A bi-directional air track exists in the flow path between uninvolved spaces and the fire compartment. Hot gases will exit the fire compartment and flow into the hallway, filling areas open to the fire compartment at the upper level. Prior to flashover the fire will become ventilation limited and become more ventilation limited as the fire becomes fully developed in Bedroom 1 and flames extend into the hallway. As oxygen inside the house is used by the fire and oxygen concentration decreases, HRR and flaming combustion will be reduced. However, combustion will continue in the fire compartment and heat transfer in adjacent areas will result in continued pyrolysis, increasing the concentration of gas phase fuel in the smoke.

As in Scenario 1, conditions will vary considerably throughout the dwelling depending on location and height above the floor. However, areas open to the fire compartment are likely to be smoke logged (filled with smoke). Temperatures will be lower and oxygen concentration will likely be higher in areas remote from the fire. As the HRR continues to decrease, temperatures will slowly begin to drop throughout the building.

Conditions at the lower levels remote from the fire may remain tenable for some time and even with close proximity to the fire compartment, Bedroom 2 with the closed door is also likely to provide tenable conditions for some time.

Alternate Scenarios

The two scenarios presented are but a small fraction of possible conditions that could exist in this building. Failure of a window, partial closing of a door (or doors), fuel type, the specific location of the occupants (on the bed versus on the floor) can all impact on potential fire conditions and survivability. All of which are not fully known to responding firefighters (who simply know that they have persons reported, and their observation of B-SAHF (Building, Smoke, Air Track, Heat, and Flame) indicators.

Tactical Options

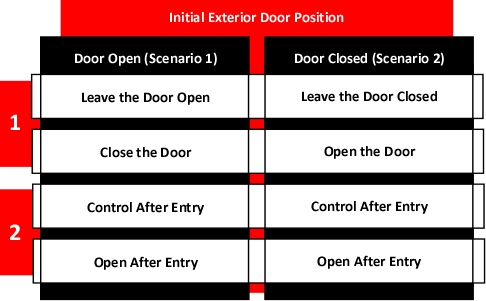

This tactical discussion will focus on the issue of door control, and as such the variable of fire control tactics will be held constant by stating that given building configuration and access, the fastest approach to getting water into the fire compartment is by making access through the front door.

There are two basic decision points related to door control. Should the position of the door be changed immediately (e.g., during 360o reconnaissance) and should the door be open or controlled (partially closed) from the time the hoseline is stretched to the interior until water is effectively applied to the fire.

Each of these decisions must be made in a timely manner and knowing when and if you will control the door should be a key element of your firefighting doctrine. In making this decision, it is essential to recognize that tenable conditions for trapped occupants and control of the fire environment to permit entry for fire control and primary search are both important considerations.

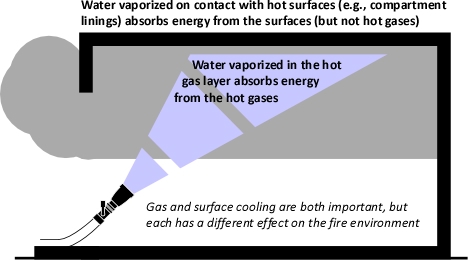

Close the Door: If the door is open, closing it will have several impacts on fire behavior. HRR will diminish and temperature within the building will be reduced. However, the smoke level will likely drop lower to the floor, but this effect will vary with location.

Open the Door: If the door is closed, opening it prior to a charged hoseline being in place will introduce fresh air (and oxygen). However, the effects of this action will occur primarily along the flow path between the opening and the fire (having limited effect on occupants in any other location). In addition, the additional air will increase the HRR from the fire. Increased HRR will likely overwhelm the limited ventilation provided by the opening, causing the upper layer to drop, with a small area of clear air at floor level just inside the door.

Door Control After Entry: If the door is controlled (partially closed) after entry, the flow of both hot smoke and air in the flow path between the fire and the front door will be reduced, limiting the increase in HRR and slowing fire progression in the upper layer between the fire and the entry point. Controlling the door after entry generally requires commitment of at least one member to door control and aiding in movement of hose through the controlled opening.

Door Open After Entry: If the door is open after entry, flow of hot smoke and air between the fire and the front door will increase as the fire receives additional oxygen and HRR increases. Extension of flames and ignition of gas phase fuel in the upper layer between the fire and the entry point is likely and should be anticipated. Access and egress through the door and for advancement of hose is unimpeded if the door remains in an open position.

The outcome of each of these choices is impacted by the distance between the entry point/ventilation opening and the fire (this influences both the speed with which the fire reacts to additional air and the time that it will take to advance the hoseline into a position where a direct attack can be made on the fire).

Unanswered Questions

Research conducted by the Underwriters Laboratories Firefighter Safety Research Institute (UL FSRI) and others have measured temperature, heat flux oxygen concentration, carbon monoxide, and carbon dioxide in the fire environment during full scale experiments (Kerber, 2011, 2013). Other tests have examined the range of toxic products in the fire environment and determined that carbon monoxide is not an effective proxy measure for overall risk of exposure to toxic products (Fabian, Baxter, & Dalton, 2010; Regional Hazardous Materials Team HM 09-Tualatin Valley Fire & Rescue Office of State Fire Marshal, 2011; Bolstad-Johnson, D., Burgess, J., Crutchfield, C., Storment, S., Gerkin, R., &Wilson, J., 2000).

Toxic effects resulting from exposure to products of combustion and pyrolysis are dependent on the dose (concentration x time) and the time over which that dose is received. However, potential survival is also impacted by potential thermal insult which depends on temperature, heat flux, and time. The potential variations in specific combustion and pyrolysis products present and thermal conditions in the fire environment is not limitless, but is nearly so. So what actions can be taken to reduce the risk to occupants who have been unable to egress the building prior to the arrival of fire companies?

Proactive Action Steps

While this post examines tactical options, the ideal outcomes is to prevent the fire from occurring in the first place, to increase the potential for occupants to escape prior to the development of untenable conditions, or for occupants to take refuge in a manner that will provide a tenable environment until the fire service can remove the threat or aid the occupants in their escape. Proactive steps would include the following:

- Home safety surveys to identify fire hazards and reduce the risk of fire occurrence as well as ensuring that homes have working smoke detectors and a home fire escape plan.

- Public education and fire code requirements to encourage or require residential sprinklers to increase the potential time for occupants to escape.

- Public education on the value of sleeping with your door closed and closing doors when escaping from a fire.

- Dispatch protocols to prompt occupants to close doors as they exit or to take refuge behind a closed door if they cannot escape.

- Train other emergency response personnel such as law enforcement and emergency medical services regarding the importance of not increasing ventilation to vent limited fires.

However, once a fire occurs and the fire department responds, our actions can have a significant impact on the outcome.

Firefighting Doctrine

The starting point for defining doctrine is to first, recognize that there is no single answer or silver bullet that will provide an optimal outcome under all circumstances. A second consideration is that you will never (this is one of the only absolutes) have enough information to clearly and definitively know exactly what is happening, what will happen next, and what impact your actions will have (you should have a good idea, but will not know with complete certainty). Starting points for thinking about integrating door control and anti-ventilation into your firefighting doctrine include:

- Research (Kerber, 2011, 2013) has provided solid evidence that when water cannot be immediately applied to the fire, closing the door will generally improve conditions on the interior. That said, there may be times when door control may not be necessary or may be contraindicated.

- If water can immediately be applied to the fire from the point of entry or within close proximity to the point of entry (e.g., the fire is not shielded), door control may not be needed prior to direct attack (but likely will not make things worse if it is performed).

- Control of doors in the flow path to confine hot smoke and fire gases may make operations safer and improve tenability for both trapped occupants and firefighters (think about the Isolate in Vent, Enter, Isolate, and Search (VEIS)).

Doctrine should be based on evidence provided by research and fireground experience. Both are necessary, but neither is sufficient.

The purpose of research is not to choose sides; it’s simply to provide data to help validate the debatable points of a chosen tactic and provide a greater degree of certainty for a recommended tactic. Keep in mind, with facts in hand, the fireground remains a dynamic situation and no tactic can or should ever be considered absolute. The goal is to provide as much factual information as possible so we can make informed decisions before, during and after the fire (Sendelbach, 2014).

Understanding the evidence provided by fire dynamics research cannot be developed by simply reading the Tactical Considerations or Executive Summary of a research report. Dig a bit deeper and examine the research questions and how the research was conducted. Consider the evidence, as research continues additional questions will be answered and our understanding of the fire environment and impact of tactical operations will continue to improve and likely have further impact on what we do on the fireground.

References

Sendelbach, T.(2014). Becoming better informed on the fireground. Retrieved July 5, 2015 from http://www.firefighternation.com/article/command-and-leadership/becoming-better-informed-fireground.

United States Fire Administration (USFA). (2013a). Civilian fire fatalities in residential buildings (2009–2011). Retrieved July 5, 2014 from http://www.usfa.fema.gov/downloads/pdf/statistics/v14i2.pdf

United States Fire Administration (USFA). (2013b) One- and two-family residential building fires (2009-2011). Retrieved July 5, 2014 from http://www.usfa.fema.gov/downloads/pdf/statistics/v14i10.pdf

Kerber, S. (2011). Impact of ventilation on fire behavior in legacy and contemporary residential construction. Retrieved July 5, 2014 from http://www.ul.com/global/documents/offerings/industries/buildingmaterials/fireservice/ventilation/DHS%202008%20Grant%20Report%20Final.pdf

Kerber, S. (2013). Study of the effectiveness of fire service vertical ventilation and suppression tactics in single family homes. Retrieved July 17, 2013 from http://ulfirefightersafety.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/UL-FSRI-2010-DHS-Report_Comp.pdf

Fabian, T., Baxter, C., & Dalton, J. (2010). Firefighter exposure to smoke particulates. Retrieved July 5, 2014 from http://www.ul.com/global/documents/offerings/industries/buildingmaterials/fireservice/WEBDOCUMENTS/EMW-2007-FP-02093.pdf

Regional Hazardous Materials Team HM 09-Tualatin Valley Fire & Rescue Office of State Fire Marshal (2011). A study on chemicals found in the overhaul phase of structure fires using advanced portable air monitoring available for chemical speciation. Retrieved July 5, 2014 from http://www.oregon.gov/osp/sfm/documents/airMonitoringreport.pdf

Bolstad-Johnson, D., Burgess, J., Crutchfield, C., Storment, S., Gerkin, R., &Wilson, J. (2000). Characterization of firefighter exposures during fire overhaul. Retrieved July 5, 2014 from http://www.firefightercoexposure.com/CO-Risks/