Social Learning

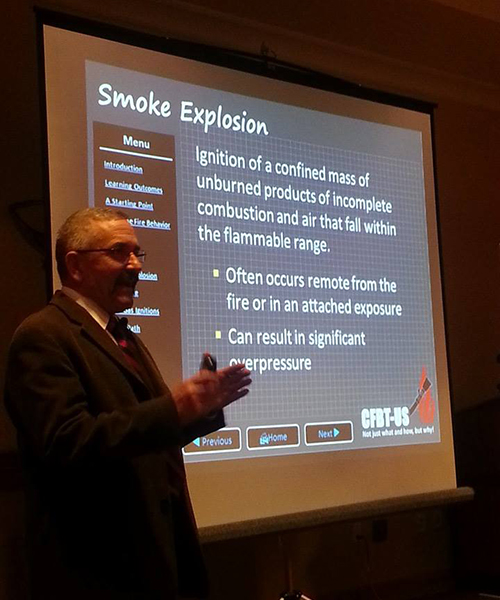

Last week, at the Underwriters Laboratories (UL) Firefighter Safety Research Institute (FSRI) Advisory Board Meeting, we discussed changes in the fire environment over the last 40 years and also explored how to effectively roll out the new UL Vertical Ventilation on-line course. On my flight home, was checking Facebook and found several interesting questions from Colin Patrick Kelley and Scott Corrigan related to my blog post titled Integration which encouraged readers to integrate the tactical considerations and lessons learned from the UL Horizontal and Vertical Ventilation Studies (Kerber, 2010, 2013). Scott had reposted a link to Integration on Facebook and after having a look at the Tactical Integration Worksheet, Colin commented with an interesting question for Scott and I. The fire environment is not the only thing that has changed in the last 40 years! Almost every day, I interact with firefighters from around the world through my blog, social media, VOIP telephone or video, e-mail, and a host of other technological innovations. The tools that allow us to interact with a worldwide network have also changed dramatically (likely as much as the fire environment) in the same timeframe.

Social learning can occur as either a formal, organization-driven process or as an informal employee-driven process…networks of people belonging to all professions, working across time and space, can make informed decisions and solve complex problems in ways they couldn’t dream of years ago. By bringing together people who share interests, no matter their location or time zone, social media has the potential to transform the workplace into an environment where learning is as natural as it is powerful (ASTD, 2011, p. 1-2)

It is important for us to consider how we use formal (e.g., training and education), informal (e.g., company drills and discussions), and social (e.g., use of social media, blogs) learning as part of our professional development as firefighters and fire officers. Take advantage of opportunities for learning in each of these areas. Be curious, think critically, and learn continuously!

The Questions

Collin explains his perspective and poses a question. Scott replies and redirects the question to me. This type of dialog is an excellent example of how we can use social learning to deepen our understanding and learn from the experience of others.

Colin Patrick Kelley writes: This is great stuff & memory aids are always appreciated by a numbskull like me. But I’m having some trouble. Scott Corrigan or Chief Ed Hartin, can you help me out with one of the categories listed on the Tactical Integration Worksheet? It reads as follows:

Large Vertical Vents are Good, But…. A 4’ x 8’ ventilation opening removed a large amount of hot smoke and fire gases. However, without water on the fire, the increased air supply caused more products of combustion to be released than could be removed through the opening, overpowering the vertical vent and worsening conditions on the interior. Once fire attack returned the fire to a fuel controlled regime, the large opening was effective and conditions improved (Hartin, 2013)

Collin Patrick Kelly continues: I feel like this tactical tidbit is missing a vital piece of info. Hear me out. If we know that horizontal openings (doors & windows) begin as bi-directional ventilation openings or flow paths (high side exhaust and low side inlets )that can and will eventually become almost all exhaust if left alone to burn and track long enough and we also know that vertical openings (cut holes, skylights, scuttles) are always going to start off as Unidirectional Flow paths or ventilation openings ( all exhaust) and will stay this way throughout the fire. Then how did the vertical opening aid in the fires growth? It aided in fire growth because the vertical vent studies were all done with the front door open and therein lies the problem. This front door was the low air inlet that the fire needed for growth. And in fact, during the Governors Island scuttle (vertical vent) test, when they opened the scuttle at the top of the stairs and closed the front door conditions began to get better and this was before a drop of water was sprayed. Temps began to decrease because as Steve Kerber put it “we are releasing more energy than the fire can produce”, in effect, stopping the “wood stove” scenario (another Kerber quote), which is the perfect scenario for fire growth. Low horizontal inlet and then up and out vertically. It stated above that “the increased air supply caused the fire to grow and overpower the vent opening”. I think it is critical to state that door control coupled with vertical vent can be a winning combination and in many instances the least risky and most effective means of ventilation. Was this either of your understandings of the study vs. the Governors Island tests and if so should that one listing contain a bit more specificity in its definition and understanding?

Scott Corrigan replied: Great input and shows you are closely watching [and] not [simply] relying on the footnotes of others. Door control to avoid the intake is key to all entry, when you are not going to apply water. It becomes part of a synchronized intake with you open it with the attack team advancing on the fire, not waiting to see flames, but comfortable flowing the line into smoke. Any tactical ventilation (PPA, Horizontal and Vertical) that is conducted without water application will produce ill results. The key is to continue to understand the cohesion of all the elements and the true coordination of fire attack and tactical ventilation. Sometimes putting a couple of sentences together can lead others see things as less than positive. I have had some great discussions with brilliant people about the “perceived” negatives of vertical ventilation. I think to frame it properly when discussing tactical ventilation is that we all agree (at least we should) that it needs to be in support of fire attack. Kevin Story from Houston says, “Engine work without truck work can suck, Truck work without Engine work can be disastrous.”. Ed Hartin what do you think regarding the Vertical Vent information Colin poses above?

Ian Bolton added to the conversation: You mentioned ‘It aided in fire growth because the vertical vent studies were all done with the front door open and therein lies the problem’ I think what you may be referring to is the possibility of providing an outlet, but without an inlet, perhaps by keeping the front door closed. Well, one thing that is sometimes not considered regarding ventilation is that for smoke/hot fire gases to be able to leave an environment, an equal amount/mass of air needs to replace it. It all goes back to the good old Law of Conservation of Mass from the mid-1700s. Stating that the mass of the system must remain constant over time, as system mass cannot change quantity if it is not added or removed. And of course when we are relating this to ventilation, the mass we are considering is our air/smoke/fire gases etc. So for us to be able to release those hot gases, they will need to be replaced by fresh air, either via a door, window, building leakage or some other means.

The Integration Worksheet accomplished its task as it stimulated thought and discussion about how these various tactical considerations should be integrated. Steve Kerber and I discussed the varied and in some cases misguided interpretation of the study results last week. Both studies presented data that support the effectiveness of coordinated fire attack and ventilation with vertical ventilation being generally more effective than horizontal, but not always necessary for effective operations in private dwellings. Both studies also supported the concept that uncoordinated horizontal or vertical ventilation of a ventilation controlled fire would result in increased heat release rate and worsening fire conditions.

Collin’s post includes a number of statements that frame his question:

- Horizontal openings (doors & windows) begin as bi-directional ventilation openings or flow paths ( high side exhaust and low side inlets )that can and will eventually become almost all exhaust if left alone to burn and track long enough.

- Vertical openings (cut holes, skylights, scuttles) are always going to start off as Unidirectional Flow paths or ventilation openings (all exhaust) and will stay this way throughout the fire.

- [The vertical ventilation opening] aided in fire growth because the vertical vent studies were all done with the front door open… This front door was the low air inlet that the fire needed for growth.

Question: Was this either of your understandings of the [vertical ventilation] study vs. the Governors Island tests and if so should that one listing contain a bit more specificity in its definition and understanding?

The Foundation

It is important to ensure that we share a common understanding of terminology and concepts. The following are important to this discussion of practical fire dynamics and tactical ventilation:

Ventilation: The exchange of the atmosphere inside a compartment or building with that outside the compartment or building. Ventilation is going on all the time, even when there is no fire. Under fire conditions, ventilation may be changed by creation of openings by exiting occupants, fire effects, or by other human action.

Tactical Ventilation: Planned, systematic, and coordinated removal of hot smoke and fire gases and their replacement with fresh air. Actions ranging from opening a door to make entry, breaking or opening a window, or cutting an opening in the roof can all be part of tactical ventilation.

Tactical Anti-Ventilation: Planned, systematic, and coordinated confinement of hot smoke and fire gases and exclusion of fresh air. Closing or controlling the door to limit inflow of air is an anti-ventilation tactic.

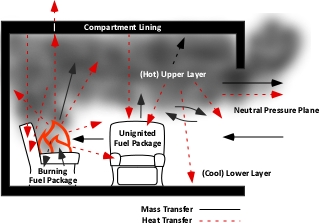

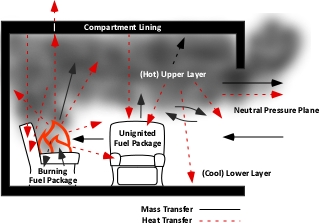

Conservation of Mass: The mass of air entering a compartment (single compartment or building) must equal the mass of smoke and air exiting the building. This means that other than in the extremely short term, if smoke is exiting the building, air must be entering. This may be through one or more openings functioning solely as inlets or openings may be functioning as both inlets and outlets (with either a bi-directional flow or alternating (pulsating) flow). However, the mass of the inflow must equal that of the outflow.

Flow Path: The flow path is the volume between inlet(s), the fire, and outlet(s).

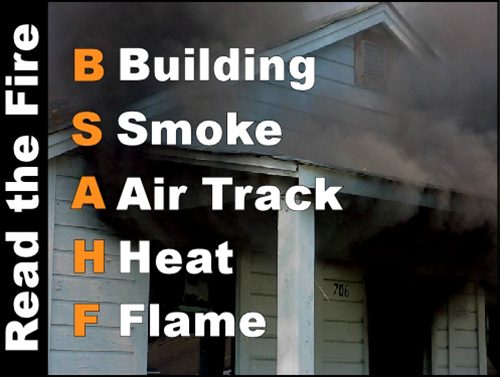

Air Track: While not used extensively in the scientific literature, the term air track as used in 3D Firefighting: Training, Techniques, and Tactics (Grimwood, Hartin, McDonough, & Raffel, 2005) may be used to describe the movement of smoke and air within the flow path. If the flow path is thought of as a road (path), movement of vehicles along the road would be the air track.

Bidirectional Air Track: A bi-directional air track is movement of smoke out and air in along the same flow path or at an opening.

Unidirectional Air Track: A unidirectional air track is movement of air or smoke in a single direction along a flow path or at an opening.

Impact of Differences in Elevation of Openings: As demonstrated in both the horizontal and vertical ventilation tests conducted by UL, the greater the difference in height between the inlet and the outlet, the more effective the ventilation. Given the buoyancy of hot smoke, making an exhaust opening above the height of the inlet increases effectiveness of both horizontal and vertical ventilation. Vertical ventilation resulted in greater gas movement (smoke out and air in) under similar conditions.

Exhaust and Inlet Openings: The relationship of the size of the exhaust opening(s) and inlet opening(s) has a significant effect on the efficiency of tactical ventilation. With natural ventilation, the total area of the inlet(s) should be larger than that of the exhaust opening(s). With equal sized openings, efficiency will vary depending on the temperature of the gases, but at 500o C, efficiency is likely to be approximately 70%. Higher temperatures result in increased efficiency, while lower temperatures result in decreased efficiency. Increasing the size of the inlet to twice that of the exhaust will increase efficiency to approximately 90%. Further increases in inlet size result in diminishing increases in efficiency (Svensson, 2000).

Tactical Considerations: As used in the UL reports on Horizontal and Vertical Ventilation and their accompanying on-line training programs, tactical considerations are things to think about in application of firefighting strategies and tactics based on the results of experimental research in. The tactical considerations are not rules or procedures, but serve to inform our practice and also to raise additional questions to be answered (e.g., do these same considerations apply in other types of buildings or with different building geometry?).

Discussion

The following section addresses Colin’s statements and question.

Bi-Directional Air Track from Horizontal Openings: Collin indicated that horizontal openings begin with a bi-directional air track and as the fire develops transition to almost all exhaust. Horizontal Openings may present a bi-directional air track (smoke out the top and air in the bottom), this is common (but not exclusively) when the opening is at the same level as the fire and is a typical indicator of a ventilation controlled fire. Under these conditions, the area of opening serving as an exhaust increases as the fire develops and temperature of the hot gases exiting through the opening increase. As a result the area of the opening serving as an inlet will decrease. Mass balance is maintained as the cooler outside air is more dense (greater mass per unit volume) than the hot gases that are exiting. So far so good, this is consistent with Colin’s first assumption.

However, several conditions may result in a unidirectional, outward flow of smoke from a horizontal opening. First, if the opening is above the fire and another (lower) inlet is present, the opening may have a unidirectional, outward flow. Second, if the opening is on the leeward (downwind) side and an inlet is present on the windward (upwind) side of the building, a unidirectional, outward flow of smoke may be present. Conversely, these conditions also may result in a unidirectional, inward flow at the inlet opening.

Horizontal openings may also present with a pulsing (inward and outward flow) under extremely ventilation controlled conditions. This air track is an indicator of potential for a ventilation induced flashover or backdraft.

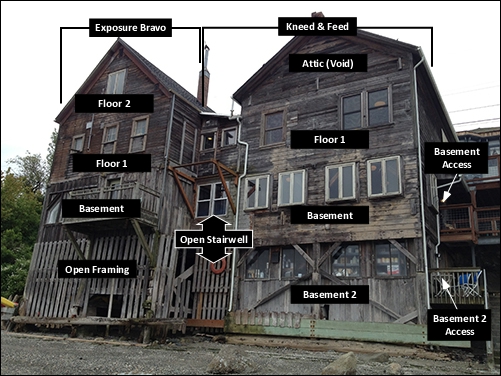

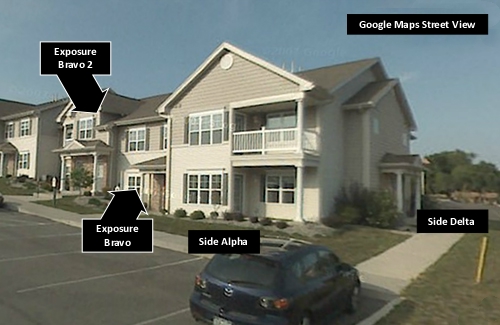

The following video is an excellent illustration of B-SAHF (building, smoke, air track, heat, and flame) indicators, the concept of flow path, anti-ventilation, tactical ventilation, door control, and a host of other interesting things. This test was conducted by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) in Bensenville, IL. The building is a wood frame townhouse with a fire ignited on the first floor. The door on Floor 1, Side Alpha is closed and the window on Side 1, Alpha is open. The door to the second floor room where the open window is located is also open, providing a flow path between the window and the first floor fire. While the second floor window is not a vertical vent, it is above the fire and at different points in the test showed a bi-directional and unidirectional air track.

At the start of the video, the air track is bi-directional and while continuing in this mode, becomes substantially and exhaust opening. Pay close attention at 03:36 as the fire becomes more ventilation controlled and the air tack begins to pulse, alternating between inlet and exhaust. At 03:46, smoke discharge from the window ceases as the opening becomes an inlet (or at least not an exhaust). This condition continues until the door is opened at 04:06. Once the door is opened, the window becomes an exhaust while the door maintains a bidirectional air track, serving as both an exhaust and inlet for the remainder of the test.

Important! Changes in air track are as (or likely even more) important as the direction (in, out, bidirectional, or pulsing (in and out)).

Unidirectional, Outward Air Track from Vertical Openings: Collin states that vertical openings will always going to start off and remain unidirectional (all exhaust) throughout the fire. Two factors influence movement of smoke (and air), differences in density (mass per unit volume) and pressure. Increased temperature (in comparison with ambient temperature of the outside air) reduces the density of smoke, making it buoyant. The same increased temperature in combination with the confinement provided by the building results in (slightly) increased pressure. Both of these factors influence movement of smoke and the tendency of vertical (or the upper area of horizontal) openings to serve as an exhaust.

I agree with Colin that vertical openings generally will serve as an exhaust point throughout the incident. However, the extent to which they do so is dependent on the presence of one or more inlet openings as well as the buoyancy and pressure resulting from the fire’s heat release rate.

The following video was taken as part of a NIST (2003) research project examining structural collapse. While focused on building performance, this video clearly demonstrates another one of the UL tactical considerations; nothing showing means exactly that, nothing. In particular, note conditions at 2:30, 4:40, and 5:30 in the video.

Changes in discharge from existing vertical building openings continues to be an exhaust, but at a significantly diminished flow. Additional detail is provided in the prior CFBT-US blog post Influence of Ventilation in Residential Structures: Tactical Implications Part 3 (Hartin, 2011). For more information on these tests, see Structural Collapse Fire tests: Single Story, Ordinary Construction Warehouse (Stroup, Madrzykowski, Walton, & Twilley, 2003) and additional video on the NIST web site.

It is also important to consider the impact of wind and fire conditions on the function of vertical openings, wind effects or cooling of smoke due to severely ventilation limited conditions may impact on smoke movement and the function of vertical openings as an exhaust.

Integration

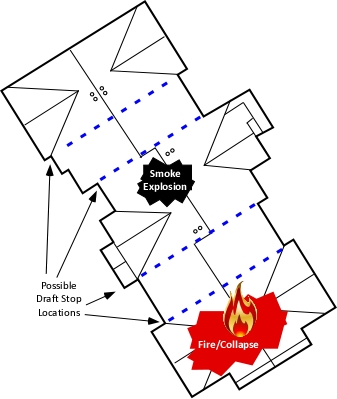

Integration of the tactical considerations presented in the Horizontal and Vertical Ventilation Studies requires a deeper look. Each of the considerations must be framed in context. Both studies were experimental in nature, meaning that as many variables as possible were controlled to allow data directly related to ventilation to be collected. In that the fires needed to be extinguished to preserve the structures for subsequent experiments, data on the interrelationships between fire attack and ventilation were also collected. However, tactical operations were not conducted in exactly the same manner as they would on the fireground. Ventilation openings were precut, durable materials were used for window coverings rather than glass, and fire attack was limited to exterior streams. These variations from the typical fireground provided consistency from experiment to experiment and between series of tests (e.g., horizontal and vertical) that allowed valid and reliable analysis of data related to ventilation and exterior fire attack.

There are a number of tactical considerations identified in the Horizontal and Vertical Ventilation Studies that are interrelated (see the Tactical Integration Worksheet):

You Can’t Vent Enough (Horizontal) & Large Vertical Vents are Good, But…(Vertical): Ventilation (either horizontal or vertical) presents a bit of a paradox. Hot smoke and fire gases are removed from the building, but the fresh air introduced provides oxygen to the fire resulting in increased heat release rate. In the horizontal ventilation study, each successive increase in horizontal ventilation released additional smoke, but also provided an increased air supply to the fire. In the vertical ventilation study, a 4’ x 8’ ventilation opening removed an even larger amount of hot smoke and fire gases. However, without water on the fire to reduce the heat release rate and return the fire to a fuel controlled regime, the increased air supply caused more products of combustion to be released than could be removed through the opening, overpowering the ventilation openings and worsening conditions on the interior. Once fire attack returned the fire to a fuel controlled regime, the large opening was effective and conditions improved. This held true in all experiments in both studies!

Coordination (Horizontal) & Coordinated Attack Includes Vertical Ventilation (Vertical): The Horizontal Ventilation Study identified that the window of time between increased ventilation and transition to conditions that were untenable for both building occupants and firefighters was extremely short. This held true with vertical ventilation as well. Vertical ventilation is the most efficient type of natural ventilation, it not only removes a large amount of smoke, but it also introduces a large amount of air into the building (the mass of smoke and air out must equal the mass of air introduced). If uncoordinated with fire attack, the increase in oxygen will result in increased fire development and heat release. However, once fire attack is making progress, vertical ventilation will work as intended, with effective and efficient removal of smoke and replacement with fresh air.

Gaining Access is Ventilation (Horizontal) & Control the Access Door (Vertical): If a fire is ventilation limited, additional oxygen will increase the heat release rate. The entry point is a ventilation opening that not only allows smoke to exit, but also provides additional atmospheric oxygen to the fire, increasing heat release rate and speeding fire development. Keep in mind that the entry point is a ventilation opening and don’t open it until ready to initiate fire attack. Controlling the door after entry (closed as much as possible while allowing the hose to pass) slows fire development and limits heat release rate. Once the fire attack crew has water on the fire and is limiting heat release by cooling the door can and should be opened as part of planned, systematic, and coordinated tactical ventilation.

Expanded Tactical Considerations

Colin was correct in his assertion that the statement “Large Vertical Vents are Good, But…” needs a bit more detail. Each of the tactical considerations presented in the UL Horizontal and Vertical Ventilation studies needs to be integrated with one another along the operational context of your department. Some of the considerations will be the same, regardless of if you are a member of FDNY or Central Whidbey Island Fire & Rescue, others will be different. Large organizations with substantial resources will be challenged by coordination (what must be done concurrently or in close sequence) while smaller organizations with fewer resources are challenged to a greater extent by sequence (what comes first, second, and third). However, regardless of the context, the fire dynamics remains the same.

The following tactical considerations related to vertical ventilation are based in part on the research results and tactical considerations developed by the UL Firefighter Safety Research Institute, ongoing study of practical fire dynamics, and fireground operations, over the last 40 years.

- The air track from vertical ventilation openings in or directly connected to the involved area of the building is most likely to be unidirectional, and outward.

- The air track from horizontal ventilation openings above the fire is likely to be unidirectional, outward, may be bidirectional (out at the top and in at the bottom), or may be pulsing (in and out).

- The air track from horizontal openings on the same level as the fire is likely to be bidirectional, but may be unidirectional, outward or inward or it may be pulsing (in and out).

- The air track from horizontal openings below the level of the fire is likely to be unidirectional, inward, but may present differently depending conditions.

- Air track is influenced by the location and size of openings, the distance of the opening from the fire, wind conditions, the burning regime (fuel or ventilation controlled), and if ventilation controlled, the extent to which ventilation is limited. As with all of the B-SAHF (building, air track, heat, smoke, and flame), air track must always be considered on context.

- Larger vertical ventilation openings will release a larger amount of smoke and a correspondingly large volume of air will be introduced into the building.

- With natural tactical ventilation, if the area of the inlet or inlets is small in relation to the exhaust opening, the movement of both smoke and air will be constrained and ventilation will be less efficient. Correspondingly if the area of the inlet or inlets is large movement of smoke and air will be more efficient.

- When using natural tactical ventilation, the inlet area should whenever possible be two or three times the size of the exhaust opening (note that this is reversed when using positive pressure ventilation).

- If the fire is in a fuel controlled burning regime, effective vertical tactical ventilation will provide a lift in the smoke level and slow fire development even if fire attack is delayed. This was commonly seen in the legacy fire environment, but is unlikely in the modern fire environment due to the high heat release rate of modern fuels and fuel loads found in today’s buildings.

- If the fire is ventilation controlled (most likely in the modern fire environment) and either horizontal or vertical tactical ventilation is performed absent fire attack, the lift (if it occurs) will be momentary as increased heat release rate and smoke production will likely overwhelm the size of the ventilation opening.

- If the fire is ventilation controlled, the effectiveness of vertical tactical ventilation on improving conditions is dependent on concurrent application of water onto the fire. Note that this requires effective fire attack, not simply a charged line at the door or being advanced into the building. Once ventilation openings are created, the clock is ticking on increased heat release rate.

- Coordinating fire attack and vertical tactical ventilation requires close communication between companies assigned to fire attack and those assigned to ventilation. Communication when water is being applied to the fire is critical. However, it is also important to evaluate observed conditions in conjunction with reports from the interior.

- If using existing vertical openings such as skylights, scuttles, or roof bulkheads, it may be necessary to delay opening until the hoseline is in place and operating.

- Vertical ventilation through cut openings takes longer than using existing openings and as such hoselines may be in place and operating before the hole is completely cut. However, it is important for company or team performing ventilation to verify that this is the case before opening the cut hole.

- Effective coordination between fire attack and ventilation requires that command and company officers have a good idea of how long specific tactical operations take in different types of buildings and with varied construction types. If you don’t know, it is time to get dirty and find out!

Closing Thoughts

Remember that “training and learning are not the same thing… Training is an outside in approach to providing quantifiable content” (ASTD, 2011, p. 3) many firefighters and firefighters correctly perceive that training is what is done to you. Learning on the other hand; “is an inside out process that originates with the learner’s desire to know” (ASTD, 2011, p. 3). Training and learning are both important! Social learning does not replace training, it may overlap and reinforce training, but it can also enable the transfer of knowledge in a way that training cannot.

I would like to thank Colin Patrick Kelley, Scott Corrigan, and Ian Bolton for engaging in a bit of Social Learning and helping me do the same! Be curious (but not simply in a passive way, ask questions), think critically (ask questions and probe, consider “so what”, “now what”, and why as critical tools in your toolbox), and learn continuously (learning is an inside out process that starts with you).

Stay up to date with the latest UL research with the fire service by connecting with the Firefighter Safety Research Institute on the web or liking them on Facebook. Integrate this information with what you currently know and engage in deliberate practice to master your craft!

References

American Society of Training and Development. (2011) Social learning. Retrieved August 24, 2013 from http://www.astd.org/Certification/For-Candidates/~/media/Files/Certification/Competency%20Model/SocialLearning1.ashx

Grimwood, P., Hartin, E., McDonough, J., & Raffel, S. (2005) 3D firefighting: Training, techniques, and tactics. Stillwater, OK: Fire Protection Publications.

Hartin, E. (2013) Integration [blog post]. Retrieved August 24, 2013 from https://cfbt-us.com/wordpress/?p=1926

Hartin, E. (2011) Influence of Ventilation in Residential Structures: Tactical Implications Part 3. Retrieved August 25, 2013 from https://cfbt-us.com/wordpress/?p=1666

Kerber, S. (2010). Impact of ventilation on fire behavior in legacy and contemporary residential construction. Retrieved July 17, 2013 from http://www.ul.com/global/documents/offerings/industries/buildingmaterials/fireservice/ventilation/DHS%202008%20Grant%20Report%20Final.pdf.

Kerber, S. (2013). Study of the effectiveness of fire service vertical ventilation and suppression tactics in single family homes. Retrieved July 17, 2013 from http://ulfirefightersafety.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/UL-FSRI-2010-DHS-Report_Comp.pdf

Stroup, D. Madrzykowski, D., Walton, W., & Twilley, W. (2003) Structural collapse fire tests: Single story, ordinary construction warehouse. Retrieved August 25, 2013 from http://www.nist.gov/customcf/get_pdf.cfm?pub_id=861215