Close the Door!

Were You Born in a Barn?

Thursday, May 30th, 2013

Coming and going as a little kid, I frequently would forget to close the door to the house and my mother would say; close the door! Were you born in a barn? What does this have to do with firefighting operations? As it turns out, it has significant impact!

Research conducted by Underwriters Laboratories (UL), National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), and the Fire Department of the City of New York (FDNY) points to the importance of close coordination of tactical ventilation (including opening a door to gain access) and fire attack. While doors are not ordinarily considered a firefighting tool, this post examines door control as an essential element in firefighting operations.

The Fire Environment-A Quick Review

Modern homes have a high fire load (both in mass and heat of combustion of common building contents), are better insulated and more energy efficient, and are larger and have large open, undivided living spaces.

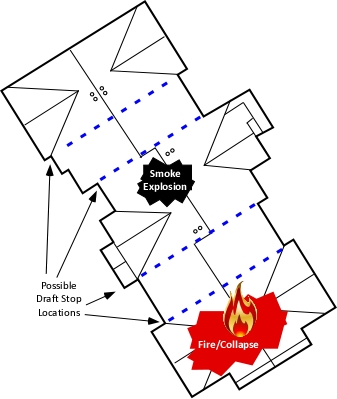

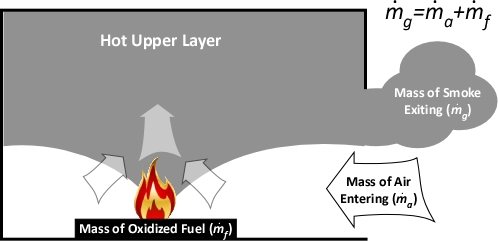

These conditions often result in rapid fire development and transition from a growth stage, fuel controlled burning regime to decay stage, ventilation controlled burning regime prior to the arrival of the fire department. Increased ventilation (without concurrent fire control) will result in increased heat release rate, returning the fire to the growth stage and rapid transition through flashover to a fully developed stage of fire development.

A number of factors influence the speed with which heat release rate accelerates when the air supplied to a ventilation controlled fire increases. These include building and compartment size and geometry, thermal conditions, and size and location of the ventilation openings.

- In general, fires in smaller compartments will react more quickly, but compartmentation and complex geometry will slow air movement from the inlet to the fire, and resulting increase in HRR.

- Introduction of air close to the fire will influence HRR more quickly than air introduced at a distance.

- Exhaust openings that are above the fire (horizontal or vertical) will increase HRR more quickly and to a greater extent than those at the same level (but may be more effective in improving conditions when fire control is established)

- Larger openings (or multiple smaller openings) will increase HRR to a greater extent and more quickly than smaller (or fewer) openings.

Conditions on Arrival

A critical element of size-up is identification of the current ventilation profile of the building. Remember that ventilation (exchange of the atmosphere inside the building and that outside the building) is always going on to one extent or another. Assessment of the ventilation profile is based on the Building, Smoke and Air Track elements of B-SAHF (Building, Smoke, Air Track, Heat, and Flame) Fire Behavior Indicators (FBI). Starting with Building factors, consider the nature of current ventilation openings:

- No significant ventilation openings (normal building leakage only)

- One or more doors may be open

- One or more windows may be open

- Some combination of door(s) and window(s) may be open

In addition to the ventilation openings, it is important to consider if they are exhaust openings, inlets, both exhaust and inlet, and what is visible; flames or smoke:

- Nothing showing (remember that this means nothing, the fire may be ventilation controlled and in the decay stage, but interior temperatures may be above 425o C (800o F) even when little or nothing is showing from the exterior.

- Smoke showing from ventilation openings (consider the direction of the air track at each opening, in, out, bi-directional, or pulsing)

- Smoke and flames showing from ventilation openings (as with smoke, consider the direction of the air track)

Structural Firefighting is Simple

OK this is a bit of an overstatement (actually more than a bit). Generally, there are only two things that firefighters can do to influence fire behavior; change the ventilation or absorb the energy being released by the fire. Read each of the following three scenarios and consider the questions posed. While examining door control, this anti-ventilation tactic is not used alone so there are a few questions that address fire control tactics (which will be the subject of a subsequent post).

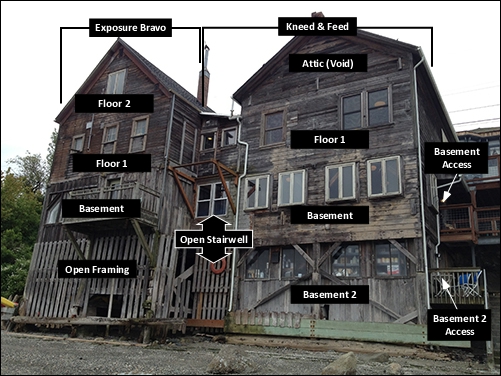

Scenario 1: The first arriving company arrives to find a small volume of smoke showing from around windows and doors and from the eaves on Side Alpha with low velocity, no air inlet is obvious. Performing a 360o reconnaissance, the officer observes similar smoke and air track indicators on other sides of the building and that all doors and windows are closed. Several windows on Side Alpha (Alpha Bravo Corner) are darkened with condensed pyrolysis products and the home appears to have smoke throughout (smoke logged).

- How do you think the fire will develop between arrival and initiation of offensive fire attack (assuming that adequate resources are on-scene for offensive operations) assuming no change in ventilation prior to fire attack.

- How would opening the front door prior to having a charged line at the doorway on Side Alpha impact fire development?

- How would horizontal ventilation of the fire compartment (Alpha/Bravo Corner) impact fire development if performed as soon as the hoseline is deployed to the (still closed) doorway on Side Alpha?

- What would be the impact on fire behavior if the engine company advanced the first hoseline to the windows; took the glass and applied water to the burning fuel inside the fire compartment prior to making entry through the door? How might this change if offensive fire attack was delayed (e.g., insufficient staffing for offensive operations)?

- How would opening the front door and horizontal ventilation of the fire compartment (Alpha/Bravo Corner) impact fire development if performed as soon as the hoseline is deployed to the doorway on Side Alpha?

- Assuming that sufficient resources are on-scene to permit an offensive attack, when should the entry point be opened? Assuming that the door is unlocked, how should this task be approached?

- Once the hoseline is deployed into the building through the door on Side Alpha for offensive fire attack, should the door remain fully open or closed to the greatest extent possible? Why?

- Assuming that this is a contents fire and horizontal ventilation will be appropriate, when and where should it be performed (describe the flow path from inlet to exhaust)?

Scenario 2: The first arriving company arrives to find smoke showing with moderate velocity and a bi-directional air track (smoke out the top and air in the bottom) from an open door on Side Alpha. A moderate volume of smoke is also pushing from around windows and from the eaves on Side Alpha. Several windows on Side Alpha (Alpha Bravo Corner) are darkened with condensed pyrolysis products and a glow is visible inside in the room behind these windows. Performing a 360o reconnaissance, the officer observes similar smoke and air track indicators on other sides of the building and that all doors and windows with the exception of the door on Side Alpha are closed. Returning to Side Alpha, the officer observes that the velocity of smoke from the open door has increased and flames at the interface between the smoke and air as it exits the doorway. The home appears to have smoke throughout (smoke logged).

- How do you think the fire will develop between arrival and initiation of offensive fire attack (assuming that adequate resources are on-scene for offensive operations) assuming no change in ventilation prior to fire attack.

- How would the officer closing the front door prior to having a charged line at the doorway on Side Alpha (e.g., when performing the 360) impact fire development?

- Assuming that sufficient resources are on-scene to permit an offensive attack and the door was closed during the 360, when should the entry point be opened? How should this task be approached?

- How would horizontal ventilation of the fire compartment (Alpha/Bravo Corner) impact fire development if performed as soon as the hoseline is deployed to the open doorway on Side Alpha?

- Once the hoseline is deployed into the building through the door on Side Alpha for offensive fire attack, should the door remain fully open or closed to the greatest extent possible? Why?

- Assuming that this is a contents fire and horizontal ventilation will be appropriate, when and where should it be performed (describe the flow path from inlet to exhaust)?

Scenario 3: The first arriving company arrives to find smoke showing with moderate velocity and a bi-directional air track (smoke out the top and air in the bottom) from an open door on Side Alpha. A moderate volume of smoke is also pushing from around windows and from the eaves on Side Alpha. Flames are visible from several windows on Side Alpha (Alpha Bravo Corner) with a bi-directional air track (flames from the upper ¾ of the window with air entering the lower ¼). Performing a 360o reconnaissance, the officer observes similar smoke and air track indicators on other sides of the building and that all doors and windows with the exception of the two windows and door on Side Alpha are closed. Returning to Side Alpha, the officer observes that the velocity of smoke from the open door has increased and flames at the interface between the smoke and air as it exits the doorway. Flames from the windows on Side Alpha are similar to when first observed. The home appears to have smoke throughout (smoke logged).

- How do you think the fire will develop between arrival and initiation of offensive fire attack (assuming that adequate resources are on-scene for offensive operations) assuming no change in ventilation prior to fire attack.

- How would the officer closing the front door prior to having a charged line at the doorway on Side Alpha (e.g., when performing the 360) impact fire development?

- Assuming that sufficient resources are on-scene to permit an offensive attack and the door was closed during the 360, when should the entry point be opened? How should this task be approached?

- How would horizontal ventilation of the fire compartment (Alpha/Bravo Corner) impact fire development if performed as soon as the hoseline is deployed to the open doorway on Side Alpha?

- Once the hoseline is deployed into the building through the door on Side Alpha for offensive fire attack, should the door remain fully open or closed to the greatest extent possible? Why?

- Assuming that this is a contents fire and horizontal ventilation will be appropriate, when and where should it be performed (describe the flow path from inlet to exhaust)?

- Assuming that this is a contents fire and horizontal ventilation will be appropriate, when and where should it be performed?

These questions were all based on a similar fire (different development based on the ventilation profile at the time of the first company’s arrival) in the same, simple building, a one story, wood frame dwelling. It is important to examine other levels of involvement and ventilation profiles in this building as well as other types of buildings and fire conditions with similar questions. Also give some thought to the impact of door control when using vertical ventilation in coordination with fire attack.

Door Control Doctrine

Doctrine is a guide to action rather than a set of rigid rules. Clear and effective doctrine provides a common frame of reference, helps standardize operations, and improves readiness by establishing a common approach to tactics and tasks. Doctrine should link theory, history, experimentation, and practice to foster initiative and creative thinking.

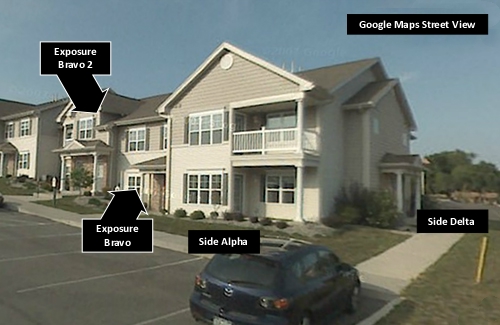

Given what we know about the modern fire environment and the influence of both existing and increased ventilation on ventilation controlled fires, what guidance should we provide to firefighters regarding door control? The following questions are posed in the context of a residential occupancy (one or two-family home, garden apartment unit, townhouse, etc.).

- If the door to the fire occupancy is open when the first company arrives, should it be (immediately) closed by the member performing the 360o reconnaissance? If so why? If not, why not?

- If the door should be closed immediately there any circumstances under which it should not? If there are circumstances under which the door should not be closed, what are they and why?

- If the door is closed on arrival (or you closed the door during the 360o reconnaissance) when and how should it be opened for entry? Think about tactical size-up at the door, forcible entry requirements, and the actual process of opening the door and making entry? How might this differ based on conditions?

- After making entry should the door be closed to the greatest extent possible (i.e., leaving room for the hoseline to pass)? If so why? If not, why not?

- If the door should be closed to the greatest extent possible, who will maintain door control and aid in advancement of the line? How might this be accomplished with limited staffing?

- If you are performing search, should doors to the rooms being searched be closed while searching? If so why? If not, why not? Are there conditions which would influence this decision? If so, what are they?

- Should the doors to rooms which have been searched be closed after completing the primary search? If so why? If not, why not? Are there conditions which would influence this decision? If so, what are they?

- How else can doors be used to aid in fire control or the protection of occupants and firefighters? Give this some thought!

Review The Influence of Ventilation in Residential Structures Part 2 for additional information on the influence of ventilation and door control as an anti-ventilation tactic.

I plan on posting my thoughts on the questions posed in this post next week. However, it would likely make this much more interesting if you post your perspectives (or additional questions) as a comment!

Ed Hartin, MS, EFO, MIFireE, CFO