Homewood, IL LODD

Introduction

While formal learning is an essential part of firefighters’ and fire officers’ professional development, informal learning is equally important, with lessons frequently shared through the use of stores. Stories are about sharing knowledge, not simply about entertainment. It is their ability to share culture, values, vision and ideas that make them so critical. They can be one of the most powerful learning tools available (Ives, 2004). “Only by wrestling with the conditions of the problem at hand and finding his own way out, does [the student] think” (Dewey, 1910, p. 188).

Developing mastery of the craft of firefighting requires experience. However, it is unlikely that we will develop the base of knowledge required simply by responding to incidents. Case studies provide an effective means to build our knowledge base using incidents experienced by others. This case is particularly significant as the circumstances could be encountered by almost any firefighter.

Aim

Firefighters and fire officers recognize and respond appropriately to the hazards of ventilation controlled fires in small, Type V (wood frame), single family dwellings.

References

National Institute for Occupationsl Safey and Health (NIOSH). (2010). Death in the line of duty: Report F2010-10. Retrieved October 22, 2010 from http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/fire/pdfs/face201010.pdf.

Ives, B. (2004) Storytelling and Knowledge Management: Part 2 – The Power of Stories. Retrieved May 6, 2010 from http://billives.typepad.com/portals_and_km/2004/08/storytelling_an_1.html

Dewey, J. (1910) Democracy and education. New York: McMillan

Learning Activity

Review the incident information and discuss the questions provided. Focus your efforts on understanding the interrelated impact of ventilation and fire control tactics on fire behavior. Even more important than understanding what happened in this incident is the ability to apply this knowledge in your own tactical decision-making.

The Case

This case study was developed using NIOSH Death in the Line of Duty: Report F2010-10 (NIOSH, 2010).

On the evening of March 30, 2010, while operating at a fire in a small single family dwelling, Firefighter/Paramedic Brian Carey and Firefighter/Paramedic Kara Kopas were assigned to assist in advancement of a 2-1/2” handline for offensive fire attack and to support primary search. Shortly after entering the building conditions deteriorated and they were trapped by rapid fire progression. Firefighter Kopas suffered 2nd and 3rd degree burns to her lower back, buttocks, and right wrist. Firefighter Carey died from carbon monoxide poisoning and inhalation of smoke and soot. A 84 year old male civilian occupant also perished in the fire.

Figure 1. Side A Post Fire

Note: National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH)

Building Information

This incident involved a 950 ft2 (88.26 m2), one-story, single family dwelling constructed in 1951. The house was of Type V (wood frame) construction with a hip roof covered with asphalt shingles. The roofline of the hip roof provided a small attic space. Sometime after the home was originally constructed an addition C was built that attached the house to a garage located on Side C. Compartment linings were drywall. The house, garage, and addition were all constructed on a concrete slab.

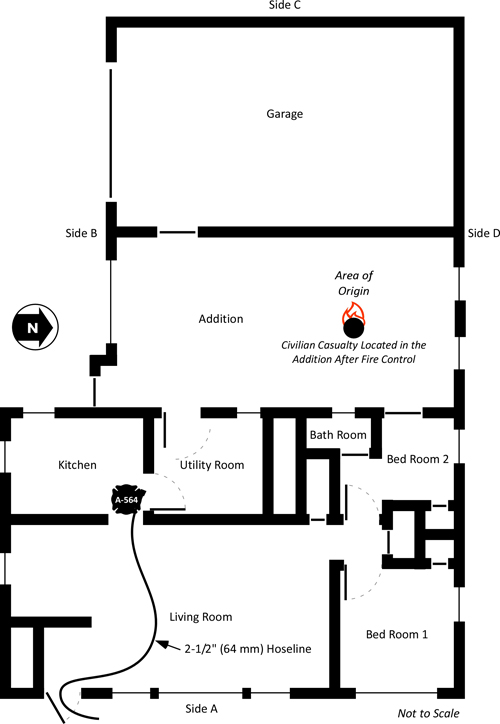

There were several openings between the house and addition, including two doors, and two windows (see Figure 3).

Note: The number and nature of openings between the garage and addition is not reported, but likely included a door and possibly a window (given typical garage construction). NIOSH investigators did not determine if the doors and windows between the house, addition, and garage were open or closed at the time of the fire as they were consumed by the fire and NIOSH did not interview the surviving occupant (S. Wertman, personal communication, November 17, 2010). The existence and position of the door shown in the wall between the addition and garage is speculative (based on typical design features of this type of structure).

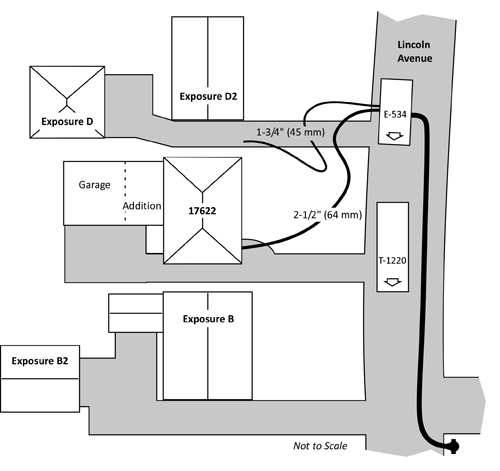

Figure 2. Plot Plan and Apparatus Positioning

Figure 3. Floor Plan 17622 Lincoln Avenue

The Fire

Investigators believe that the fire originated in an addition that was constructed between the original home and the two-car garage. The surviving occupant reported that she observed black smoke and flames from underneath the chair that her disabled husband was sitting in.

The addition was furnished as a family room and fuel packages included upholstered furniture and polyurethane padding. The civilian victim also had three medical oxygen bottles (one D Cylinder (425 L) and two M-Cylinders (34 L). It is not know if the oxygen in these cylinders was a factor in fire development. The garage contained a single motor vehicle in the garage and other combustible materials.

After calling 911 and attempting to extinguish the fire, the female occupant exited the building. NIOSH Death in the Line of Duty Report 2010-10 did not specify this occupants egress path or if she left the door through which she exited open or closed (NIOSH did not interview the occupant, she was interviewed by local fire and law enforcement authorities). The NIOSH investigator (personal communications S. Wertman, November 17, 2010) indicated that the occupant likely exited through the exterior door in the addition or through the door on Side A. Give rapid development through flashover in the addition, it is likely that the exterior door in the addition or door to the garage was open, pointing to the likelihood that the occupant exited through this door. Subsequent rapid extension to the garage was likely based on design features of the addition and garage or some type of opening between these two compartments. As similar extension did not occur in the house, it is likely that the door and windows in the Side C wall of the house were closed.

In the four minutes between when the incident was reported (20:55 hours) and arrival of a law enforcement unit (20:59), the fire in the addition had progressed from the incipient stage to fully developed fire conditions in both the addition and garage.

Dispatch Information

At 2055 hours on March 30, 2010, dispatch received a call from a resident at 17622 Lincoln Avenue stating that her paralyzed husband’s chair was on fire and that he was on oxygen. The first alarm assignment consisting of two engines, two trucks, a squad, and ambulance, and fire chief was dispatched at 2057.

Table 1. On-Duty and Additional Unit Staffing of First Alarm Resources

|

Unit |

Staffing |

|

| Engine 534 | Lieutenant, Firefighter, Engineer | |

| Ambulance 564 | 2 Firefighter Paramedics | |

| Truck 1220 (Auto Aid Department) | Lieutenant, 2 Firefighters, Engineer | |

| Engine 1340 (Auto Aid Department) | Lieutenant 3 Firefighters, Engineer | |

| Truck 1145 (Auto Aid Department) | Lieutenant, 2 Firefighters, Engineer | |

| Squad 440 (Auto Aid Department) | Lieutenant, 3 Firefighters | |

| Chief | Chief |

Note: This table was developed by integrating data from Death in the Line of Duty Report 2010-10 (NIOSH, 2010).

Weather Conditions

The weather was clear with a temperature of 12o C (53o F). Firefighters operating at the incident stated that wind was not a factor.

Conditions on Arrival

A law enforcement officer arrived prior to fire companies and reported that the house was “fully engulfed” and that the subject in the chair was still in the house.

Truck 1220 (T-1220) arrived at 2101, observed that the fire involved a single family dwelling, and received verbal reports from law enforcement and bystanders that the male occupant was still inside. Note: The disabled male occupant’s last known location was in the addition between the house and garage, but it is unknown if this information was clearly communicated to T-1220 or to Command (E-534 Lieutenant).

Engine 534 (E-534) arrived just behind T-1220 and reported heavy fire showing. E-534 had observed flames from Side C during their response and discussed use of a 2-1/2” (64 mm) handline for initial attack.

Firefighting Operations

Based on the report of a trapped occupant, T-1220B (Firefighter and Apparatus Operator) prepared to gain entry and conduct primary search. Note: Based on data in NIOSH Death in the Line of Duty Report 2010-10, it is not clear that this task was assigned by the initial Incident Commander (Engine 534 Lieutenant). It appears that this assignment may have been made by the T-1220 Lieutenant, or performed simply as a default truck company assignment for offensive operations at a residential fire.

Upon arrival, the E-534 Lieutenant assumed Command and transmitted a size-up report indicating heavy fire showing. The Incident Commander(E-534 Lieutenant) assisted the E-534 Firefighter with removal of the 1-3/4” (45 mm) skid load from the solid stream nozzle on the 2-1/2” (64 mm) hose load and stretching the 2-1/2” (64 mm) handline to the door on Side A. The E-534 Apparatus Operator charged the line with water from the apparatus tank and then hand stretched a 5” supply line to the hydrant at the corner of Lincoln Avenue and Hawthorne Road with the assistance of a Firefighter from T-1220.

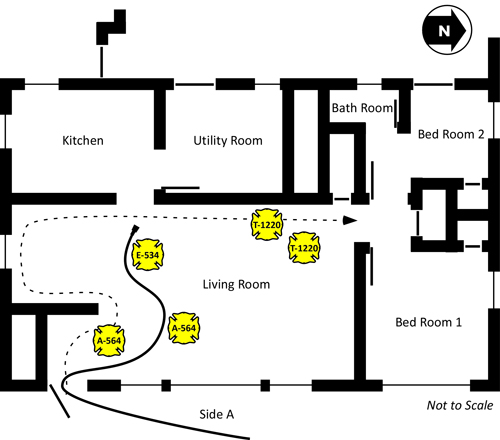

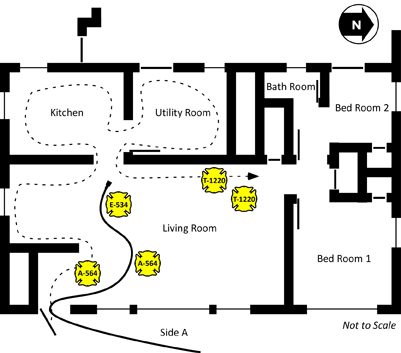

Figure 4. Initiation of Primary Search

The Incident Commander (E-534 Lieutenant) assisted T-1220B in forcing the door on Side A. T-1220B made entry without a hoseline and began a left hand search as illustrated in Figure 4, noting that the upper layer was banked down to within approximately 3’ (0.9 m) from the floor).

Arriving immediately after E-534, the crew of A-564 donned their personal protective equipment and reported to the Incident Commander at the door on Side A, where he and the E-534 Firefighter were preparing to make entry with the 2-1/2” hoseline. The Incident Commander then assigned A-564 to work with the E-534 Firefighter to support search operations and control the fire.

T-1220 initiated roof operations and began to cut a ventilation opening on Side A near the center of the roof. Note: Based on data in NIOSH Death in the Line of Duty Report 2010-10, it is not clear that this task was assigned by the initial Incident Commander (Engine 534 Lieutenant). It appears that this assignment may have been made by the T-1220 Lieutenant, or performed simply as a default truck company assignment for offensive operations at a residential fire.

As illustrated in Figure 5, a large body of fire can be observed on Side C and a bi-directional air track is evident at the point of entry on Side A with dark gray smoke pushing from the upper level of the doorway at moderate velocity. All windows on Sides A and B were intact, with evidence of soot and/or condensed pyrolizate on the large picture window adjacent to the door on Side A.

Figure 5. Conditions Viewed from the Alpha/Bravo Corner at Approximately

Note: Warren Skalski Photo from NIOSH Death in the Line of Duty Report F2010-10.

The Firefighter from E-534 took the nozzle and assisted by Firefighters Carey and Kopas (A-564) stretched the 2-1/2” (64 mm) handline through the door on Side A and advanced approximately 12’ (3.66 m) into the kitchen. As they advanced the hoseline, they were passed by T-1220B, conducting primary search. The E-534 Firefighter, Firefighter Kopas (A-564), and T-1220B observed thick (optically dense), black smoke had dropped closer to the floor and that the temperature at floor level was increasing.

Figure 6. Primary Search and Fire Control Crews

Questions

Take a few minutes and consider the answers to the following questions. Remember that it is much easier to sort through the information presented by the incident when you are reading a blog post, than when confronted with a developing fire with persons reported!

- What B-SAHF (Building, Smoke, Air Track, Heat, & Flame) indicators were observed during the initial stages of this incident?

- What stage(s) of fire and burning regime(s) were present in the building when T-1220 and E-534 arrived? Consider potential differences in conditions in the addition, garage, kitchen, bedrooms, and living room?

- What would you anticipate as the likely progression of fire development over the next several minutes? Why?

- How might tactical operations (positively or negatively) influence fire development?

Ed Hartin, MS, EFO, MIFireE, CFO

Tags: burning regime, case study, Extreme Fire Behavior, FBI, fire behavior indicators, Fire Control, fire development, firefighter fatality, firefighter injury, firefighter LODD, NIOSH, Tactical Ventilation, vent controlled fire

October 22nd, 2011 at 20:40

[…] http://cfbt-us.com/wordpress/?p=1342 Share this:TwitterFacebookEmailLike this:LikeBe the first to like this post. This entry was posted in Uncategorized by countyfiretactics. Bookmark the permalink. […]

April 3rd, 2024 at 00:45

Hello Ed. To summarize: I believe this was a Wind- Driven Fire and not aware of it, unfortunately made an Offensive Attack from the A Side. As prrssurized fire burned through the connecting door, fire blew out all created vent points including the front door. Proof: srr the 2 story home which is blocking the wind grom pressurizing the front of the invloved house but not the rear.This is why firefighters did’nt think wind was a factor but it was. See the angle of the fire and smoke over the roof indivative of a WDF. ( 45 degree angle) & finally, look closely and repeatedly at the video showing the fire blowing out the windows on the Delta Side as the fire companies arrive. A neighbor across the street comments as she video tapes the fire. Great post Ed!

April 3rd, 2024 at 00:52

Also, in all accuracy, this fire occured in 2010 when greater focus on the Wind- Driven Fire hazard had not been circulated nationally. But as you know, it will always be a concern and departments must modify their tactics to safely address these dangerous fires.