Homewood, IL LODD: Part 2

This post continues examination of the incident that took the life of Firefighter Brian Carey and seriously injured Firefighter Kara Kopas on the evening of March 30, 2010 while they were operating a hoseline in support of primary search in a small, one-story, wood frame dwelling with an attached garage at 17622 Lincoln Avenue in Homewood, Illinois.

This post focuses on firefighting operations, key fire behavior indicators, and firefighter rescue operations implemented after rapid fire progression that trapped Firefighters Carey and Kopas.

Firefighting Operations

After making initial assignments, the Incident Commander performed reconnaissance along Side Bravo to assess fire conditions. Fire conditions at around the time the Incident Commander performed this reconnaissance are illustrated in Figure 7. After completing recon of Side B, the Incident Commander returned to a fixed command position in the cab of E-534 (in order to monitor multiple radio frequencies).

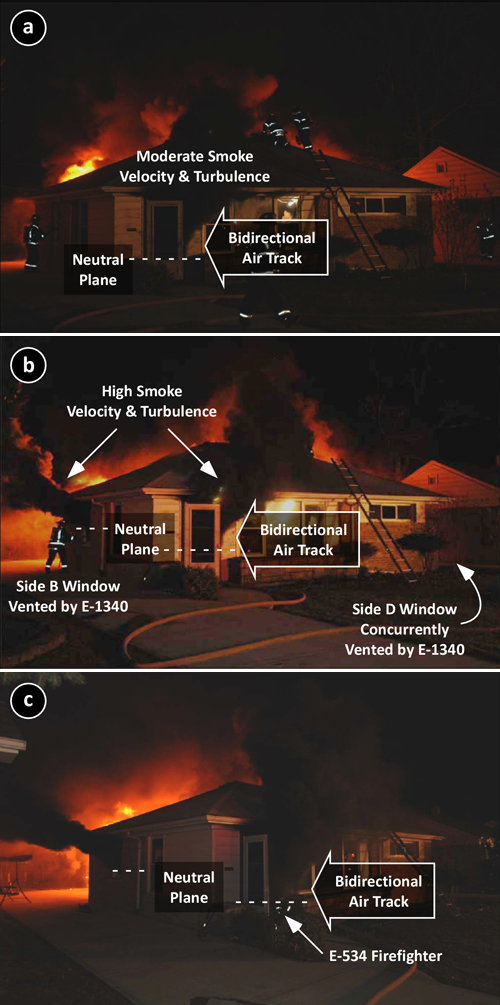

Figure 7. Conditions Viewed from Side C during the Incident Commander’s Recon

Note: John Ratko Photo from NIOSH Death in the Line of Duty Report F2010-10.

Engine 1340 (E-1340) arrived and reported to Command for assignment. The five member crew of this company was split to assist T-1220 with vertical ventilation, horizontally ventilate through windows on Sides B and D, and to protect Exposures D and D2.

One member of E-1340 assisted T-1220 and the remaining members vented the kitchen windows on SidesD and B, while the E-1340 Officer stretched a 1-3/4” (45 mm) hoseline from E-534 to protect exposures on Side D. However, this line was not charged until signficantly later in the incident (see Figure 14). Figure 8 (a-c) illustrates changing conditions as horizontal ventilation is completed on Sides B and D.

Figure 8. Sequence of Changing Conditions Viewed from the A/B Corner

At 2105 Command reported that crews were conducting primary search and were beginning to vent.

Note the B-SAHF indicators visible from the A/B Corner in Figure 8a: Dark gray smoke from the door on Side A with the neutral plane at approximately 18” (0.25 m) above the floor. Velocity and turbulence are moderate and a bidirectional air track is evident at the doorway.

As the 2-1/2” (64 mm) handline reached the kitchen, flames were beginning to breach the openings in the Side C wall of the house and thick black smoke had banked down almost to floor level. As noted in Figure 3 (and subsequent floor plan illustrations), there were doors and windows between the house and addition in the Utility Room and Bedroom 2 . The Firefighter from E-534 had a problem with his protective hood and handed the nozzle off to Firefighter Carey and instructed him to open and close the bail of the nozzle quickly. After doing so, the Firefighter from E-534 retreated along the hoseline to the door on Side A to correct this problem (he is visible in the doorway in Figure 8c).

As E-1340 vents windows on Sides B (see Figure 8b) and D, the level of the neutral plane at the doorway on Side A lifts, but velocity and turbulence of smoke discharge increases. Work continues on establishing a vertical vent, but is hampered by smoke discharge from the door on Side A.

After horizontal ventilation of Sides B and D, velocity and turbulence of smoke discharge continues to increase and level of the upper layer drops to the floor as evidenced by the neutral plane at the door on Side A (see Figures 8b and 8c)

The photo in Figure 8c was taken just prior to the rapid fire progression that trapped Firefighters Carey & Kopas. The Firefighter from E-534 is visible in the doorway correcting a malfunction with his protective hood.

As T-1220B reached the hallway leading to the bedrroms, they felt a significant increase in temperature and visibility worsened. After searching Bedroom 2 and entering Bedroom 1 temperature contiued to increase and T-1220B observed flames rolling through the upper layer in the hallway leading from Bedroom 2 and the Bathroom. Note: NIOSH Death in the Line of Duty Report 2010-10 does not specify if T-1220B searched Bedroom 2, but this would be consistent with a left hand search pattern. They immedidately retreated to the Living Room looking for the hoseline leading to the door on Side A. As they did so, they yelled to the crew on the 2-1/2” (64 mm) handline to get out.

Extreme Fire Behavior

Firefighter Kopas felt a rapid increase in temperature as the upper layer ignited throughout the living room and the fire in this compartment transitioned to a fully developed stage. She yelled to Firefighter Carey, but received no response as she turned to follow the 2-1/2” (64 mm) hoseline back to the door on Side A. She made it to within approximately 4’ (1.2 m) of the front door when her protective clothing began to stick to melted carpet and she became stuck. T-1220B saw that she was trapped, reentered and pulled her out.

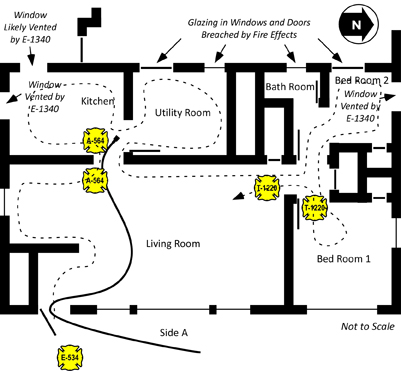

Figure 12. Position of the Crews as the Extreme Fire Behavior Phenomena Occurred

Note: It is unknown if T-1220B searched Bedroom 2 before entering Bedroom 1. However, this would be consistent with a left hand search pattern.

Figure 13. Conditions Viewed from the Alpha/Bravo Corner as the Extreme Fire Behavior Occured

Note: Warren Skalski Photo from NIOSH Death in the Line of Duty Report F2010-10.

Figure 14. Conditions Viewed from the Alpha/Delta Corner as the Extreme Fire Behavior Occured

Note: Warren Skalski Photo from NIOSH Death in the Line of Duty Report F2010-10.

Following the transition to fully developed fire conditions in the living room, the Incident Commander ordered T-1220 off the roof. As illustrated in Figure 14, the exposure protection line stretched by E-1340 was not charged until after Firefighter Carey was removed from the building.

Figure 15. Position of Search and Fire Control Crews after Rapid Fire Progress

Firefighter Rescue Operations

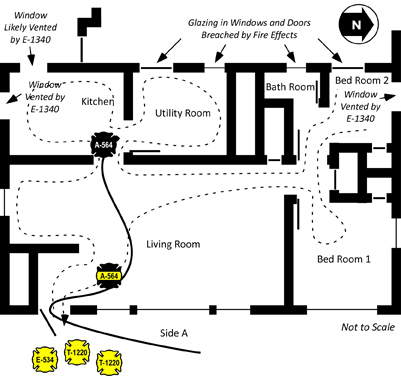

The Incident Commander and Firefighter from E-534 (who had retreated to the door due to a problem with his protective hood), pulled a second 1-3/4” (45 mm) line from E-534. T-1220B re-entered the house with this hoseline to locate Firefighter Carey.

While advancing into the living room, T-1220B discovered that E-534’s 2-1/2” (64 mm) handline. They controlled the fire in the living room using a direct attack on burning contents and advanced to the kitchen where they discovered Firefighter Carey entangled in the 2-1/2” (64 mm) handline. Firefighter Carey’s helmet and breathing apparatus facepiece were not in place.

T-1220B removed Firefighter Carey from the building where he received medical care from T-1145. A short time later, Firefighter Carey became apenic and pulseless. After the arrival of Ambulance 2101 (A-2101), Firefighter Carey was transported to Advocate South Suburban Hospital in Hazel Crest, IL where he was declared dead at 10:03 pm.

According to the autopsy report, Firefighter Carey had a carboxyhemoglobin (COHb) of 30% died from carbon monoxide poisoning. The NIOSH Death in the Line of Duty Report (2010) did not indicate if the medical examiner tested for the presence of hydrogen cyanide (HCN) or if thermal injuries were a contributing factor to Firefighter Carey’s death.

Timeline

Review the Homewood, Illinois Timeline (PDF format) to gain perspective of sequence and the relationship between tactical operations and fire behavior.

Contributing Factors

Firefighter injuries often result from a number of causal and contributing factors. NIOSH Report F2010-10 identified the following contributing factors in this incident that led to the death of Firefighter Brian Carey and serious injuries to Firefighter Kara Kopas.

- Well involved fire with trapped civilian upon arrival.

- Incomplete 360o situational size-up

- Inadequate risk-versus-gain analysis

- Ineffective fire control tactics

- Failure to recognize, understand, and react to deteriorating conditions

- Uncoordinated ventilation and its effect on fire behavior

- Removal of self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA) facepiece

- Inadequate command, control, and accountability

- Insufficient staffing

Questions

The following questions focus on fire behavior, influence of tactical operations, and related factors involved in this incident.

- What type of extreme fire behavior phenomena occurred in this incident? Why do you think that this is the case (justify your answer)?

- How did the conditions necessary for this extreme fire behavior event develop (address both the fuel and ventilation sides of the equation)?

- What fire behavior indicators were present in the eight minutes between arrival of the first units and occurrence of the extreme fire behavior phenomena (organize your answer using Building, Smoke, Air Track, Heat, and Flame (B-SAHF) categories)? In particular, what changes in fire behavior indicators would have provided warning of impending rapid fire progression?

- Did any of these indicators point to the potential for extreme fire behavior? If so, how? If not, how could the firefighters and officers operating at this incident have anticipated this potential?

- What was the initiating event(s) that lead to the occurrence of the extreme fire behavior that killed Firefighter Carey and injured Firefighter Kopas?

- How did building design and construction impact on fire behavior and tactical operations during this incident?

- What action could have been taken to reduce the potential for extreme fire behavior and maintain tenable conditions during primary search operations?

- How would you change, expand, or refine the list of contributing factors identified by the NIOSH investigators?

Tags: B-SAHF, burning regime, case study, deliberate practice, Extreme Fire Behavior, FBI, fire behavior indicators, firefighter fatality, firefighter injury, firefighter LODD, flashover, NIOSH, practical fire dynamics, reading the fire, situational awareness, vent controlled fire