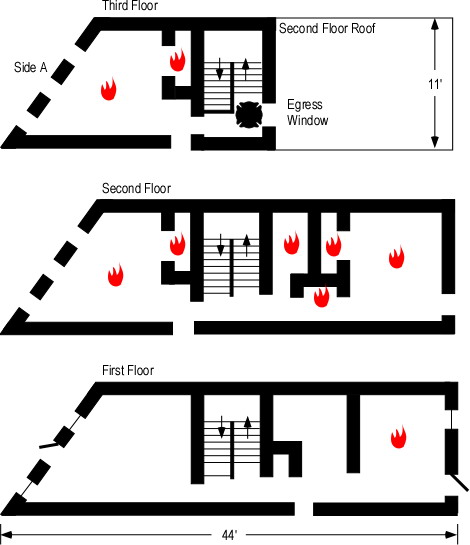

NIST Wind Driven Fire Experiments:

Anti-Ventilation-Wind Control Devices

March 9th, 2009

My last post asked a number of questions focused on results of baseline compartment fire tests conducted by the National Institute for Standards and Technology (NIST) as part of a research project on Firefighting Tactics Under Wind Driven Conditions. This post looks at the answers to these questions and continues with an examination of NIST’s experiments in the application of wind control devices for anti-ventilation.

Questions

Generally being practically focused people, firefighters do not generally dig into research reports. However, the information on the baseline test conducted by NIST raised several interesting questions that have direct impact on safe and effective firefighting operations. First consider possible answers to the questions and then why this information is so important (the “So what?”!).

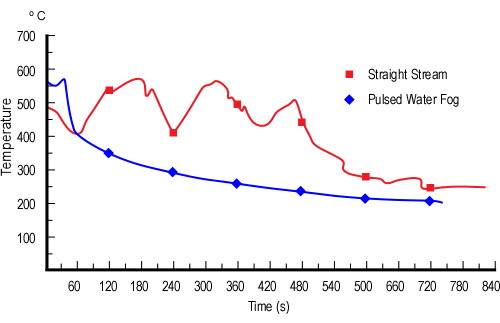

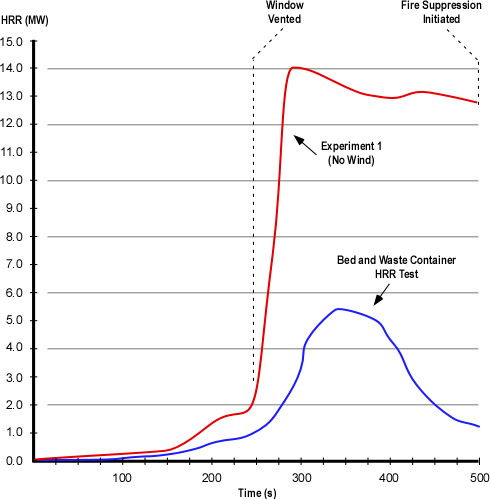

Figure 1. Heat Release Rate Comparison

Note: Adapted from Firefighting Tactics Under Wind Driven Conditions.

Heat Release Rate (HRR) Questions: Examine the heat release rate curves in Figure 1 and answer the following questions:

- Why are these two HRR curves different shapes?

- In each of these two cases, what might have influenced the rate of change (increase or decrease in HRR) and peak HRR?

- What observations can you make about conditions inside the test structure and heat release rate (in particular, compare the HRR and conditions at approximately 250 and 350 seconds)?

Answers: The HRR test for the bed and waste container was conducted under fuel controlled conditions (oxygen supply was not restricted). The higher HRR in the compartment fire experiment results from increased fuel load (e.g., additional furniture, carpet). After reaching its peak, HRR in the compartment fire drops off slowly as the fire becomes ventilation controlled and the fire continues in a relatively steady state of combustion (limited by the air supplied through the lower portion of the bedroom window)

The rate of change in heat release rate under fuel controlled conditions is dependent on the characteristics and configuration of the fuel. However, in the case of the compartment fire test, the rate of change is also impacted by limited ventilation. As illustrated in the compartment fire curve, the fire quickly became ventilation controlled and HRR rose slowly until the window failed and was fully cleared by researchers.

At 250 seconds (when the window was vented) HRR rose extremely rapidly as the fire in the bedroom rapidly transitioned from the growth through flashover to fully developed stage. At 350 seconds the fire had again become ventilation controlled and was burning in a relatively steady state limited by the available oxygen.

The fully developed fire in the bedroom also became ventilation controlled due to limited ventilation openings, resulting in HRR leveling off with relatively steady state combustion based on the available oxygen.

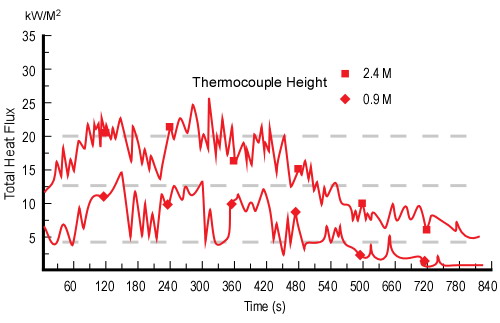

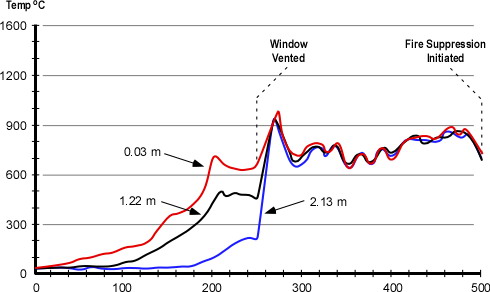

Figure 2. Bedroom Temperature

Note: Adapted from Firefighting Tactics Under Wind Driven Conditions.

Temperature Questions: Examine the temperature curves in Figure 2 and answer the following questions:

- What can you determine from the temperature curves from ignition until approximately 250 seconds?

- How does temperature change at approximately 250 seconds? Why did this change occur and how does this relate to the data presented in the HRR curve for Experiment 1 (Figure 1)?

- What happens to the temperature at the upper, mid, and lower levels after around 275 seconds? Why does this happen?

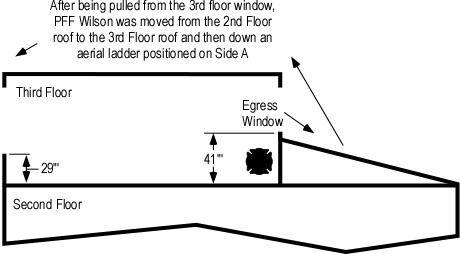

Answers: Temperature at the upper levels of the compartment increased much more quickly than at the lower level and conditions in the compartment remained thermally stratified until the ceiling temperature exceeded 600o C. At approximately 250 seconds, the compartment flashed over resulting in a rapid increase in temperature at mid and lower levels. This change correlates with the rapid increase in HRR occurring at approximately 250 seconds in Figure 1. Turbulent, ventilation controlled combustion resulted in a loss of thermal layering with temperatures in excess of 600o C from ceiling to floor. At around 275 seconds.

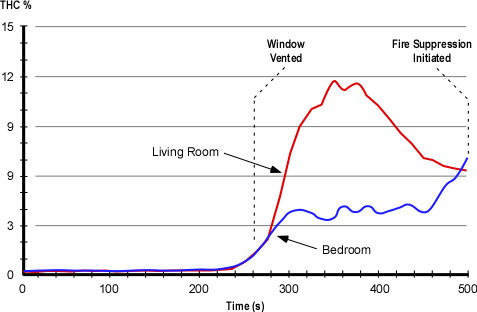

Figure 3. Total Hydrocarbons at the Upper Level

Note: Adapted from Firefighting Tactics Under Wind Driven Conditions.

Total Hydrocarbons (THC) Questions: Examine the THC curves in Figure 3 and answer the following questions:

- Why did the THC concentration in the living room rise to a higher level than in the bedroom?

- Why didn’t the gas phase fuel in the living room burn?

- How did the concentration of THC in the bedroom reach approximately 4%? Why wasn’t this gas phase fuel consumed by the fire?

Answers: Oxygen entering the compartments through the window was being used by combustion occurring in the bedroom. Low oxygen concentration limited combustion in the living room and allowed accumulation of a higher concentration of unburned fuel. While the oxygen concentration in the bedroom was higher, the fire was still ventilation controlled and not all of the gas phase fuel was able to burn inside this compartment.

So What?

What do the answers to the preceding questions mean to a company crawling down a dark, smoky hallway with a hoseline or making a ventilation opening at a window or on the roof?

Emergency incidents do not generally occur in buildings equipped with thermocouples, heat flux gages, gas monitoring equipment, and pre-placed video and thermal imaging cameras. Understanding the likely sequence of fire development and influencing factors is critical to not being surprised by fire behavior phenomena. These tests clearly illustrated how burning regime (fuel or ventilation controlled) impacts fire development and how changes in ventilation can influence fire behavior. The total hydrocarbon concentration and ventilation controlled combustion in the living room would present a significant threat in an emergency incident. How might conditions change if the fire in the bedroom was controlled and oxygen concentration began to increase? Ignition of the gas phase fuel in this compartment could present a significant threat (see Fire Gas Ignitions) or even prove deadly (future posts will examine the deaths of a captain and engineer in a fire gas ignition in California).

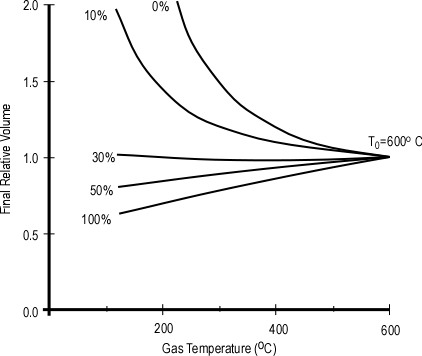

Anti-Ventilation

For years firefighters throughout the United States have been taught that ventilation is “the planned and systematic removal of heat, smoke, and fire gases, and their replacement with fresh air”. This is not entirely true! Ventilation is simply the exchange of the atmosphere inside a compartment or building with that which is outside. This process goes on all the time. What we have thought of as ventilation, is actually tactical ventilation. This term was coined a number of years ago by my friend and colleague Paul Grimwood (London Fire Brigade, retired). It is essential to recognize that there are two sides to the ventilation equation, one is removal of the hot smoke and fire gases and the other is introduction of air. Increased ventilation can improve tenability of the interior environment, but under ventilation controlled conditions will result in increased heat release rate.

Another tactic change the ventilation profile and influence fire behavior and conditions inside the building is to confine the smoke and fire gases and limit introduction of air (oxygen) to the fire. Firefighters in the United States often think of this as confinement, but I prefer the English translation of the Swedish tactic, anti-ventilation. This is the planned and systematic confinement of heat, smoke, and fire gases and exclusion of fresh air. The concept of anti-ventilation is easily demonstrated by limiting the air inlet during a doll’s house demonstration (see Figure 4). Closing the inlet dramatically reduces heat release rate and if sustained, can result in extinguishment.

Figure 4. Anti-Ventilation in a Doll’s House Demonstration

For a more detailed discussion of the relationship between ventilation and heat release rate see my earlier post on Fuel and Ventilation.

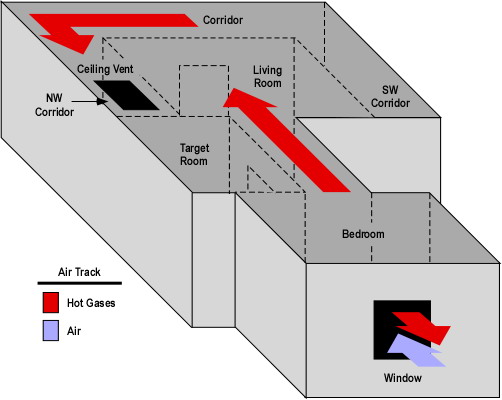

Air Track and Influence of Wind

Air track (movement of smoke and air under fire conditions) is influenced by differences in density between hot smoke and cooler air and the location of ventilation openings. However, wind is an often unrecognized influence on compartment fire behavior. Wind direction and speed can influence movement of smoke, but more importantly it can have a dramatic influence on introduction of air to the fire.

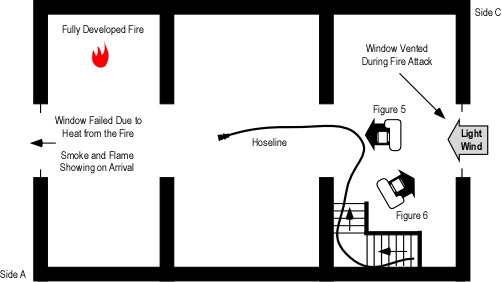

While the comparison is not perfect, the effects of wind on a compartment fire can be similar to placing a supercharger on an internal combustion engine (see Figure 5). Both dramatically increase power (energy released per unit of time).

Figure 5. Influence of Wind

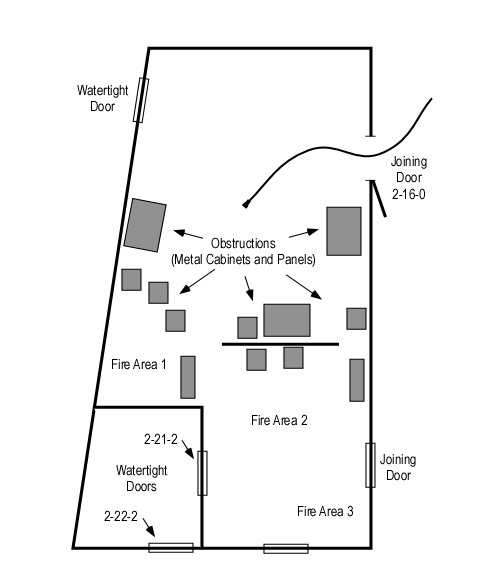

NIST Wind Control Device Tests

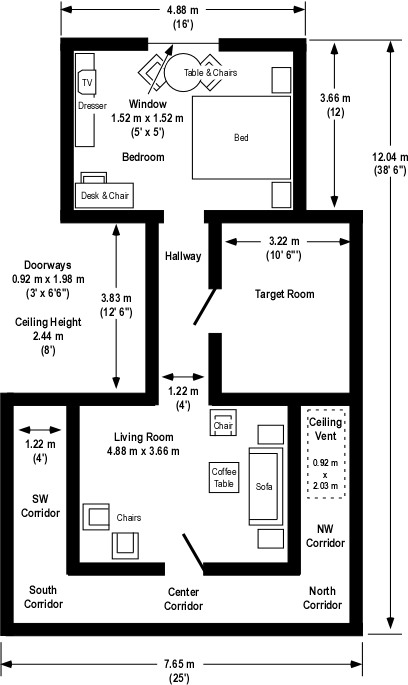

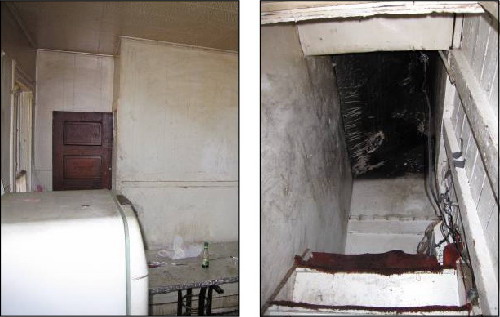

As discussed in Wind Driven Fires, the effects of wind on compartment fire behavior can present a significant threat to firefighters and has resulted in a substantive number of line-of-duty deaths. In their investigation of potential tactical options for dealing with wind driven fires, NIST researchers examined the use of wind control devices (WCD) to limit introduction of air through building openings (specifically windows in the fire compartment in a high-rise building) as illustrated in Figure 6.

Figure 6. Small Wind Control Device

Note: Photo from Firefighting Tactics Under Wind Driven Conditions.

Questions

Give some thought to how wind can influence compartment fire behavior and how a wind control device might mitigate that influence.

- How would a strong wind applied to an opening (such as the bedroom window in the NIST tests) influence fire behavior in the compartment of origin and other compartments in the structure?

- How would a wind control device deployed as illustrated in Figure 5 influence fire behavior?

- While the wind control device illustrated in Figure 5 was developed for use in high-rise buildings, what applications can you envision in a low-rise structure?

- What other anti-ventilation tactics could be used to deal with wind driven fires in the low-rise environment?

The Story Continues…

My next post will address the answers to these questions (please feel free to post your thoughts) and examine the results of NIST’s tests on the use of wind control devices for anti-ventilation.

References

Madrzykowski, D. & Kerber, S. (2009). Fire Fighting Tactics Under Wind Driven Conditions. Retrieved (in four parts) February 28, 2009 from http://www.nfpa.org/assets/files//PDF/Research/Wind_Driven_Report_Part1.pdf; http://www.nfpa.org/assets/files//PDF/Research/Wind_Driven_Report_Part2.pdf;http://www.nfpa.org/assets/files//PDF/Research/Wind_Driven_Report_Part3.pdf;http://www.nfpa.org/assets/files//PDF/Research/Wind_Driven_Report_Part4.pdf.

Ed Hartin, MS, EFO, MIFireE, CFO