Wind Driven Fires

Sunday, February 26th, 2012Seven Firefighters Injured

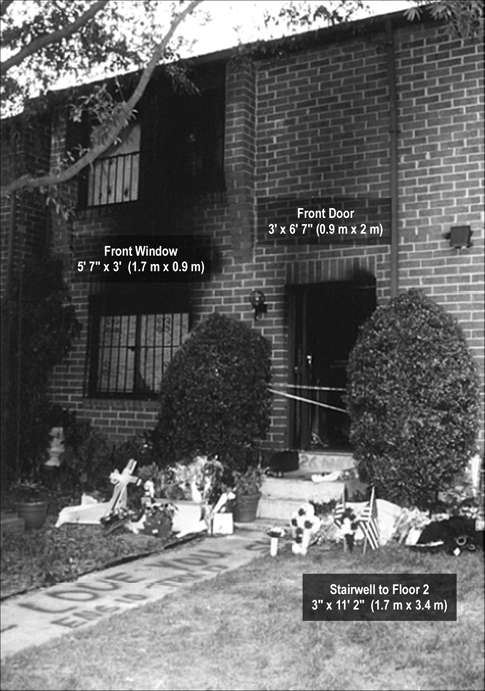

Seven firefighters were tragically injured in Prince George’s County Maryland on Friday, February 24, 2012. The fire broke out in the basement of a single-family, one-story house located at 6404 57th Avenue in Riverdale, MD shortly after 21:00 hours.

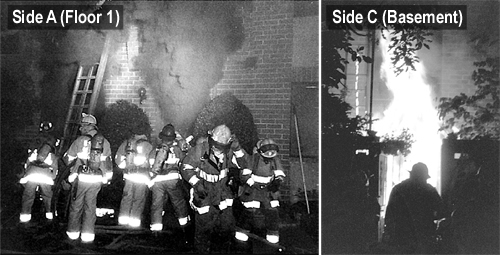

Note: View from Alpha-Bravo Corner street side. Photo by Billy McNeel.

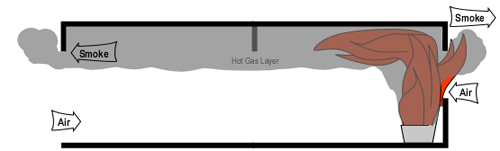

On arrival, Engine 807B reported a two-story, single family dwelling with fire showing from the basement level on Side Bravo. Seven members from Companies 807 (Riverdale) and 809 (Bladensburg) entered Floor 1 of the building on Side A (East Side) and within eight seconds were enveloped by untenable, wind driven fire conditions. Preliminary reports indicate that firefighters had initiated an interior attack on the fire when a sudden rush of air, fanned by high winds, entered from the rear of the house either from a door or window being opened or broken out. (Brady, 2012). A report on Monday, February 27 indicated that some of the firefighters ran to the back of the one-story home, then entered through a basement door while other members of their company opened the front door in search of a victim (FirefighterNation, 2012).

In a statement to Washington Post reporter J. Freedom du Lac (2012), Chief Marc Bashoor indicated that strong winds were gusting out of the west at up to 40, 45 mph, blowing directly into the burning basement, which had a west-facing door. “As soon as the guys opened the front door and advanced, it blew from the basement, up the steps and right out the front door,” Bashoor said. “It was like a blowtorch coming up the steps and out the door… Without that wind, the hot air and gases would have been venting out of the rear of the house,” he said. “The current of air essentially produced a chimney right up the steps and out the front door.” (Washington Post, 2012).

Firefighters Ethan Sorrell and Kevin O’Toole from Bladensburg Volunteer Fire Department remain in critical condition at Washington Hospital Center. Riverdale Volunteer, Michael McLary also remains hospitalized for injuries. The other injured firefighters were released and sent home Saturday evening according to the latest reports.

The wind-fueled fireball that injured seven Prince George’s County firefighters when it blew through the burning house they had just entered was “a freak occurrence,” a department spokesman, Mark Brady, said Saturday (du Lac, 2012).

Chris Naum at Command Safety has an excellent post examining the fire building and weather conditions at the time of the incident. See Residential Fire Injures Seven Firefighters: Wind Driven Conditions Suspected.

Freak Occurrence?

Dealing with an accident involving a serious injury or fatality is extremely difficult, particularly when the complete circumstances and eventual outcome is unknown. What may appear to be obvious in retrospect may also have been not so clear to the individuals engaged in emergency operations. However, one might ask if the fire behavior encountered at 6404 57th Avenue in Riverdale, MD was in fact a freak occurrence. A freak is defined as a thing or occurrence that is abnormal, markedly unusual or irregular.

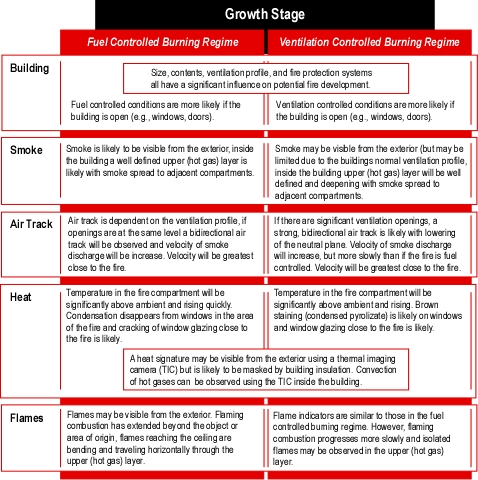

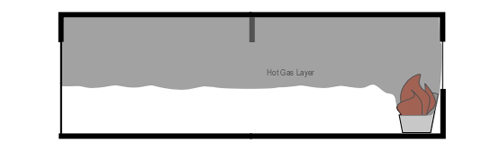

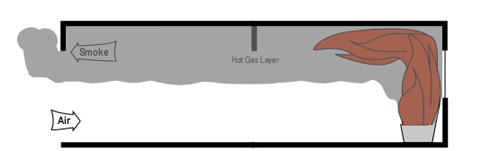

The conditions encountered were markedly different than usually encountered in fires occurring in single family dwellings. However, the conditions described in this incident are not unusual when considered in light of the building configuration and wind conditions at the time of the incident. Wind, flow path, and burning regime (fuel or ventilation controlled) have a tremendous impact on fire behavior and potential for rapid fire progression resulting in untenable conditions.

Wind Driven Fires

On April 16, 2007 Technician Kyle Wilson of the Prince William Fire & Rescue lost his life in a wind driven fire occurring in a large, single family dwelling. In the introduction to the investigative report produced by Prince William Fire & Rescue examining this incident, Chief Kevin J. McGee states:

First, the impact the wind had on this event was significant. While weather conditions, and specifically wind, are often discussed in the firefighting environment of wildland fires, it does not receive the same attention and consideration in structure fires. This incident showed the dramatic and devastating effect the wind can have on the spread of fire in a building. The wind forced the fire into the building and caused the sudden change in fire conditions inside, including the “blowtorch” effect witnessed by the crews on the scene (Prince William County Fire Rescue, 2008)

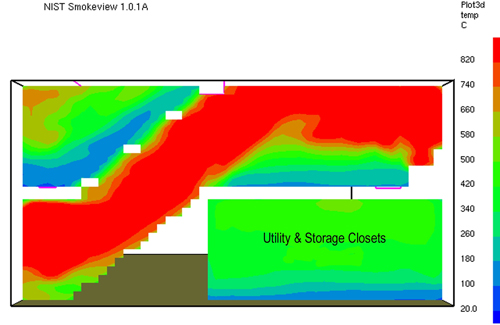

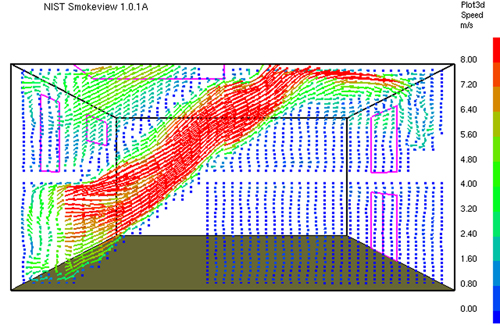

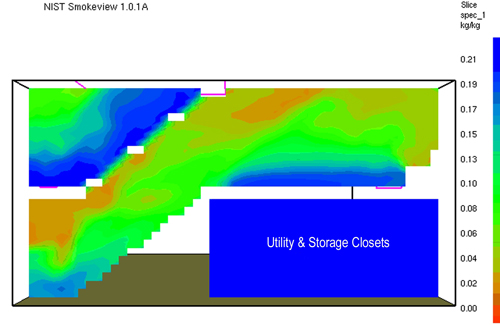

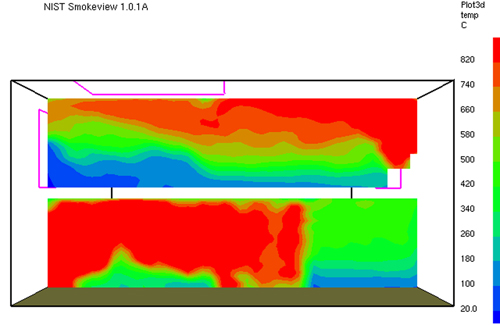

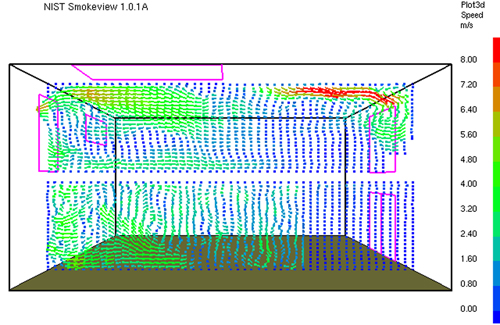

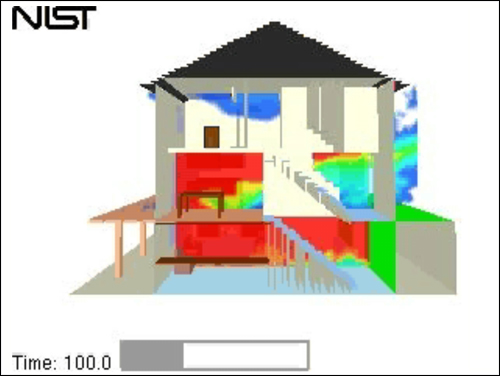

In January, the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) released Simulation of the Dynamics of a Wind-Driven Fire in a Ranch-Style House-Texas (Barowy & Madrzykowski, 2012) examining fire behavior in the incident that took the lives of Houston Fire Department Captain James Harlow and Firefighter Damion Hobbs on April 12, 2009 while engaged in firefighting operations in a single family dwelling. This report emphasized that potential for wind driven fire conditions can occur in all types of buildings, including single-family residential structures.

NIST research (Madrzykowski & Kerber.(2009a, 2009b) has identified that wind driven fire conditions can be created with wind speeds as low as 4.5 m/s (10 mph) and that while structural fire departments have recognized the impact of wind on fire behavior, in general, standard operating guidelines (SOG) have not changed to address the risk of wind driven fires (Barowy & Madrzykowski, 2012).

Previous posts have examined NISTs research on the issue of wind driven fires:

- Wind Driven Fires

- NIST Wind Driven Fire Experiments: Establishing a Baseline

- NIST Wind Driven Fire Experiments: Anti-Ventilation-Wind Control Devices

- NIST Wind Driven Fire Experiments: Wind Control Devices & Fire Suppression

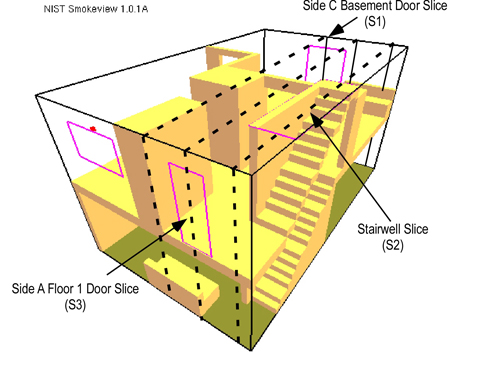

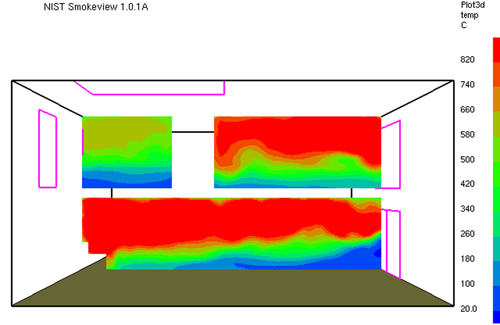

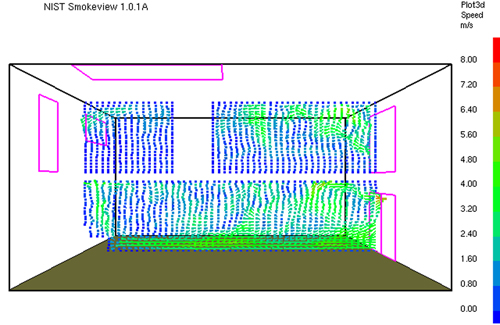

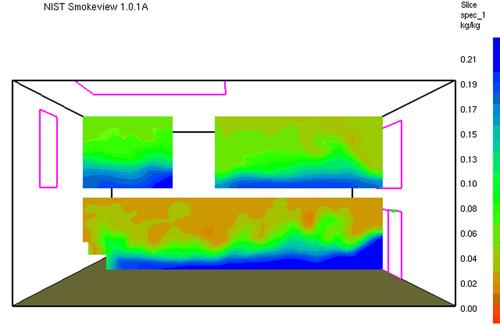

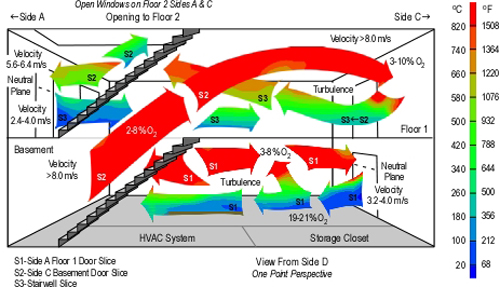

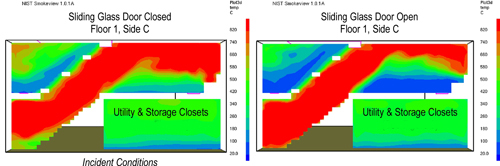

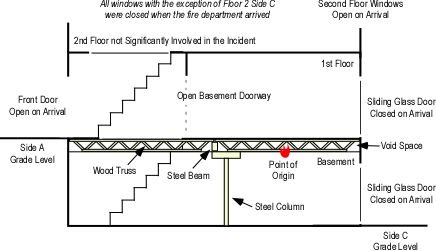

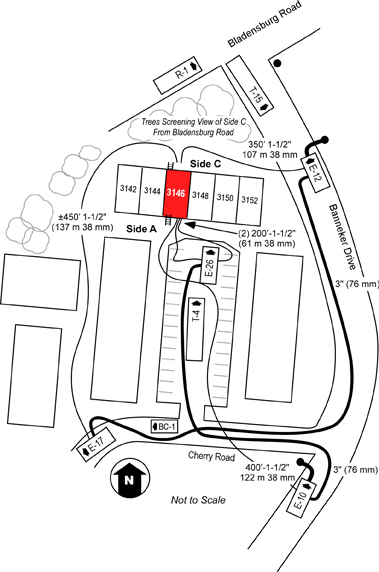

Flow Path

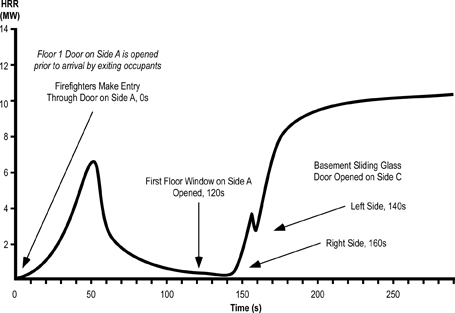

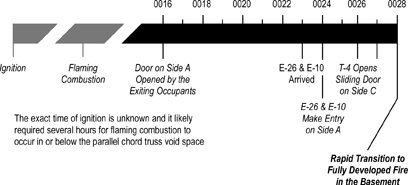

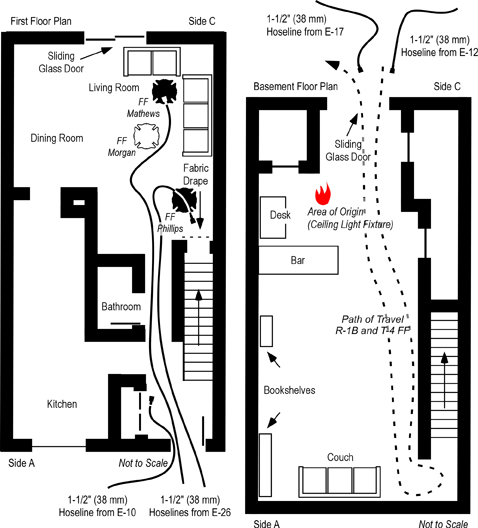

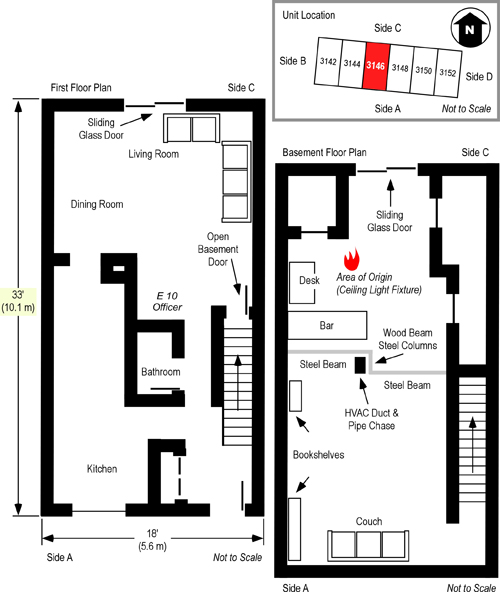

On May 30, 1999, Firefighters Anthony Phillips and Louis Matthews of the District of Columbia Fire Department (DCFD) died and two others were severely injured as a result of rapid fire progression while engaged in firefighting operations at 3146 Cherry Road, NE. The fire occurred in the basement of a two-story, middle of building, townhouse apartment. Crews entered on Floor 1, Side A and were caught in the flow path of hot smoke and flames when a sliding glass door was opened at the Basement Level on Side C. Previous posts examined this incident in detail:

- Fire Behavior Case Study Townhouse Fire: Washington, DC

- Townhouse Fire: Washington, DC What Happened

- Townhouse Fire: Washington, DC Extreme Fire Behavior

- Townhouse Fire: Washington, DC: Computer Modeling

- Townhouse Fire: Washington, DC Computer Modeling-Part 2

More recently, the City of San Francisco Fire Department released an investigative report examining the circumstances surrounding the deaths of Lieutenant Vincent Perez and Firefighter/Paramedic Anthony Valerio on June 2, 2011 while operating at a fire in the basement of a two story home with two levels below grade. Failure of a basement window placed the Lieutenant and Firefighter in the flow path between the basement window and their entry point on Floor 1. The investigative report produced by the San Francisco Fire Department details their findings and recommendations related to this incident.

Structural Firefighting Under Wind Conditions

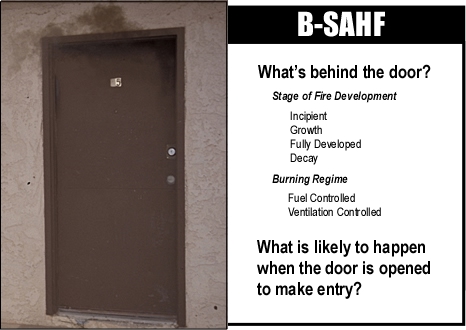

Research and fireground experience point to the following:

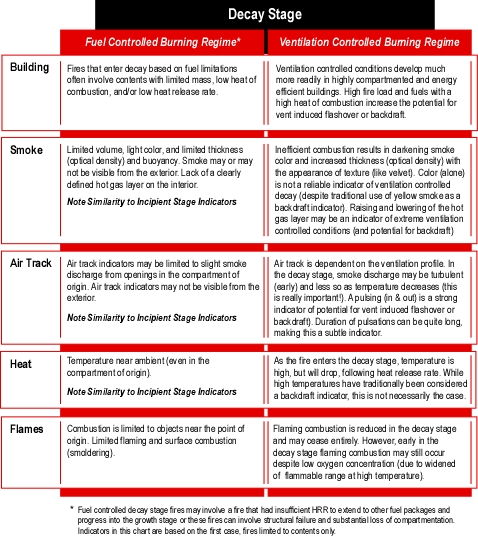

- Building configuration including windows, doors, and open interior stairways can have a significant impact on development of a flow path from the fire to one or more exhaust points.

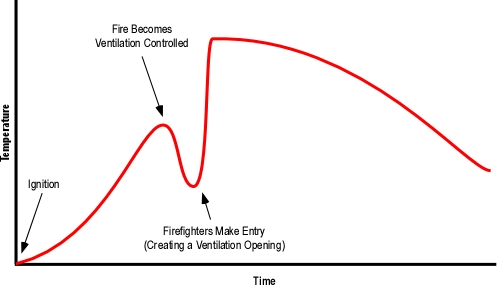

- Introduction of additional air to a ventilation controlled fire (without concurrent fire suppression) will quickly result in increased heat release rate.

- Creation of openings at and above the fire level which result in a flow path with an exhaust opening above the inlet will result in a rapid increase in heat release rate.

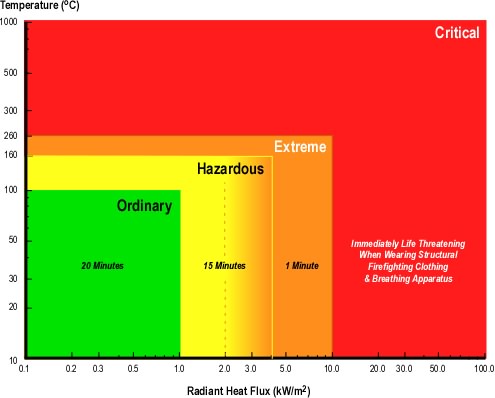

- Thermal conditions in the flow path above the fire and/or downstream from the fire location or will quickly become untenable.

- Even limited wind conditions can result in wind driven fire conditions.

- These factors in combination are even more likely to result in rapid fire progression and untenable conditions in the downstream flow path.

It is essential that Firefighters and Fire Officers recognize the influence of ventilation on fire behavior and potential for wind driven fire conditions and adjust their strategies and tactics accordingly. The following guidance is based on recommendations developed through the NIST wind driven fires research as well as data from National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) death in the line of duty reports and incident investigative reports by the Texas State Fire Marshals Office.

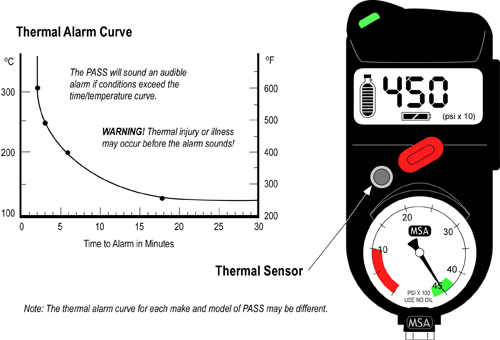

Potential for wind driven conditions increases directly with wind speed. When wind speeds exceed a gentle breeze (8-12 mph) consider the potential for wind driven fire conditions and apply the following strategic and tactical considerations (CWIFR District Board, 2011):

- If potential for wind driven fire conditions is identified, this should be communicated to all companies and members working at the incident as a safety message.

- When possible, operate from the exterior and apply water from upwind directly into the involved compartments prior to interior attack. Even low flow exterior streams applied from upwind can have a significant impact on controlling the fire prior to interior operations).

- In a wind-driven fire, it is most important to use the wind to your advantage and attack the fire from the upwind side of the structure, especially if the upwind side is the burned side. Note that this may be contrary to conventional offensive tactics that place hoselines between the hazard presented by the fire and potential occupants and uninvolved property.

- Avoid pressurization of the building without first establishing adequate exhaust openings (2-3 times larger than the inlet). Remember that wind can create the same (or greater) positive pressure as a blower used in positive pressure ventilation (PPV). Pressurization without adequate exhaust can result in extreme fire behavior. Note: This is particularly important when the fire is on the leeward (downwind) side of the building and entry is made from the windward (upwind) side of the building.

- Consider controlling the flow path by using anti-ventilation such as door control and limiting the use of (horizontal and vertical) tactical ventilation prior to fire control. However, it is essential to remember that unplanned ventilation resulting from fire effects can have a significant impact on the ventilation profile and subsequent flow path(s).

- Avoid working in the exhaust portion of the flow path (between the fire and exhaust opening) or potential flow paths (between the fire and potential exhaust openings). Unplanned ventilation from fire effects can suddenly change the interior thermal conditions.

- Identify potential refuge areas, escape routes, and safety zones prior to and during interior operations. Taking refuge in a compartment with an intact and closed door may temporarily provide tenable conditions and a place of refuge until the fire can be controlled or another avenue of egress established.

References & Additional Reading

Brady, M. (2012). Seven firefighters injured battling Riverdale house fire. Retrieved February 26, 2012 from http://pgfdpio.blogspot.com/2012/02/seven-firefighters-injured-battling.html

Central Whidbey Island Fire & Rescue (CWIFR) District Board. (2011). Board minutes February 9, 2012. Coupeville, WA: Author. [Adoption of Purpose, Policy, and Scope of SOG 4.3.6 Structural Firefighting Under Wind Conditions]

District of Columbia (DC) Fire & EMS. (2000). Report from the reconstruction committee: Fire at 3146 Cherry Road NE, Washington DC, May 30, 1999. Washington, DC: Author.

du Lac, J. (2012). Blaze that injured 7 Prince George’s firefighters called ‘freak occurrence’. Retrieved February 26, 2012 from http://www.washingtonpost.com/local/blaze-that-injured-7-prince-georges-firefighters-called-freak-occurrence/2012/02/25/gIQAdGJMaR_story.html?hpid=z3

FirefighterNation. (2012). Critically burned in Maryland house fire, firefighters face long recovery. Retrieved February 28, 2012, from http://www.firefighternation.com/article/news-2/critically-burned-maryland-house-fire-firefighters-face-lengthy-recovery.

Madrzykowski , D. & Barowy, A. (2012). Simulation of the dynamics of a wind-driven fire in a ranch-style house – Texas, TN 1729. Retrieved February 8, 2012 from http://www.nist.gov/customcf/get_pdf.cfm?pub_id=909779

Madrzykowski, D & Kerber, S. (2009a). Fire fighting tactics under wind driven conditions: Laboratory experiments, TN 1618. Retrieved February 8, 2012 from http://fire.nist.gov/bfrlpubs/fire09/PDF/f09002.pdf

Madrzykowski, D & Kerber, S. (2009b). Fire fighting tactics under wind driven fire conditions: 7-story building experiments, TN 1629. Retrieved February 8, 2012 from http://fire.nist.gov/bfrlpubs/fire09/PDF/f09015.pdf

Madrzykowski, D. & Vettori, R. (2000). Simulation of the Dynamics of the Fire at 3146 Cherry Road NE Washington D.C., May 30, 1999, NISTR 6510. August 31, 2009 from http://fire.nist.gov/CDPUBS/NISTIR_6510/6510c.pdf

National Institute for Occpational Safety and Health (NIOSH). (2008). Death in the line of duty…2007-12. Retrieved February 9, 2012 from http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/fire/pdfs/face200712.pdf

National Institute for Occpational Safety and Health (NIOSH). (2009). Death in the line of duty…2009-11. Retrieved February 9, 2012 from http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/fire/pdfs/face200911.pdf

National Institute for Occpational Safety and Health (NIOSH). (2009). Death in the line of duty…2007-29. Retrieved February 9, 2012 from http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/fire/reports/face200729.html

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). (1999). Death in the line of duty, Report 99-21. Retrieved August 31, 2009 from http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/fire/reports/face9921.html

Prince William County Department of Fire & Rescue. (2007). Line of duty death investigative report. Retrieved February 9, 2012 from http://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=2&ved=0CCgQFjAB&url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.iaff.org%2Fhs%2FLODD_Manual%2FLODD%2520Reports%2FPrince%2520William%2520County%2C%2520VA%2520-%2520Wilson.pdf&ei=b3dKT8LyGfHSiALt5tnrDQ&usg=AFQjCNFBBTfVkWIREXw0-wbd978fWSoP8w&sig2=y6_OEeJvhFSggiKioMESaw

San Francisco Fire Department. (2012). Safety Investigation Report Line-of-Duty Deaths, 133 Berkley Way, June 2, 2011, Box 8155, Incident #11050532 Retrieved February 26, 2012 from http://statter911.com/files/2012/02/Safety-Investigation-133-Berkeley-Way-Printable.pdf

Texas State Fire Marshal’s Office. (2007). Firefighter fatality investigation, Investigation Number FY 07-02. http://www.tdi.texas.gov/reports/fire/documents/fmloddnoonday.pdf

Texas State Fire Marshal’s Office. (2009). Firefighter fatality investigation, Investigation Number FY 09- http://www.tdi.texas.gov/reports/fire/documents/fmloddhouston09.pdf

Kerber, S. (2011). Impact of ventilation on fire behavior in legacy and contemporary residential construction. Retrieved July 16, 2011 from http://www.ul.com/global/documents/offerings/industries/buildingmaterials/fireservice/ventilation/DHS%202008%20Grant%20Report%20Final.pdf