Contra Costa County LODD: What Happened?

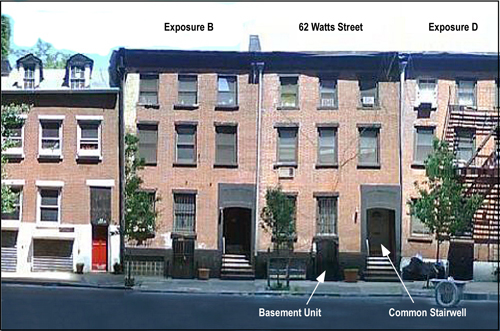

Thursday, May 14th, 2009My last two posts (Contra Costa County Line of Duty Deaths (LODD) Part 1 & Part 2) examined the conditions and circumstances involved in the incident that took the lives of Captain Matthew Burton and Engineer Scott Desmond while conducting primary search in a small residential structure in San Pablo, California early on the morning of July 21, 2007.

As identified in the Contra Costa County Investigation and NIOSH Death in the Line of Duty Report F2007-28, these line of duty deaths were the result of a complex web of events, circumstances, and actions.

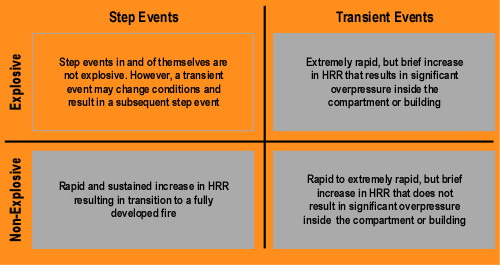

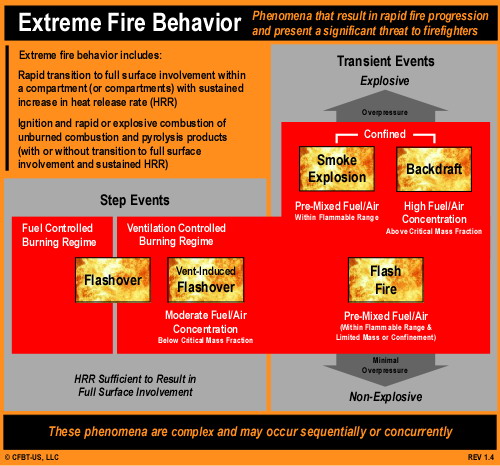

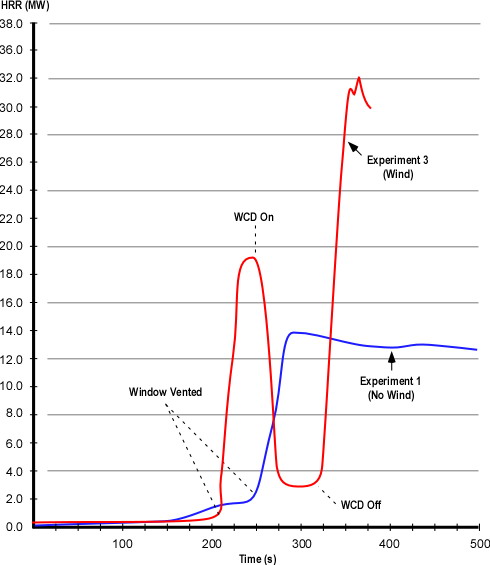

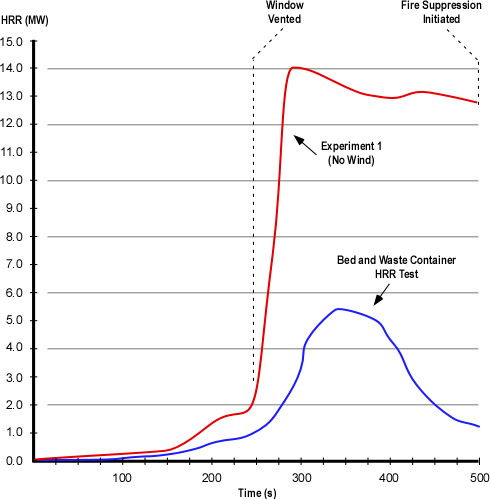

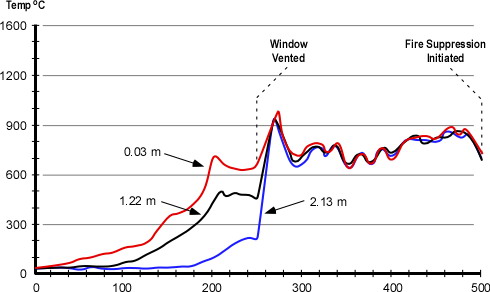

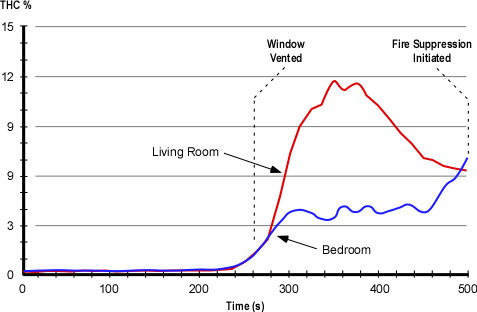

These two reports identify the rapid fire progression that trapped Captain Burton and Engineer Desmond as a fire gas ignition (county and NIOSH reports) or ventilation induced flashover (NIOSH report). Both reports also point to ineffective or inappropriate use of positive pressure ventilation as a contributing factor in the occurrence of extreme fire behavior. However, neither report provides a substantive explanation of how and why this extreme fire behavior occurred.

Investigative Approach

Developing a reasonable explanation of the extreme fire behavior that occurred in this incident involved application of the scientific method as outlined in NFPA 921 Standard on Fire and Explosion Investigations (2008).

The following analysis is based on narrative data and photographic evidence provided in the Contra Costa County Fire Protection District Investigation Report: Michele Drive Line of Duty Deaths and the video taken by the Q76 Firefighter.

In that the district and NIOSH had already collected data, this effort focused on 1) analysis of the data contained in the incident reports, photographs, and video; 2) development of a hypothesis that provided an explanation for what occurred (deductive reasoning), 3) testing this hypothesis (inductive reasoning); 4) revising the hypothesis as necessary; and 5) selecting a final hypothesis.

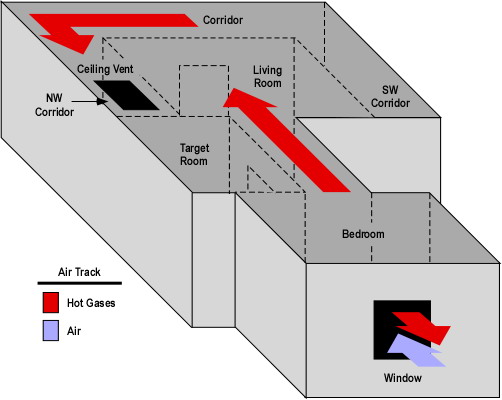

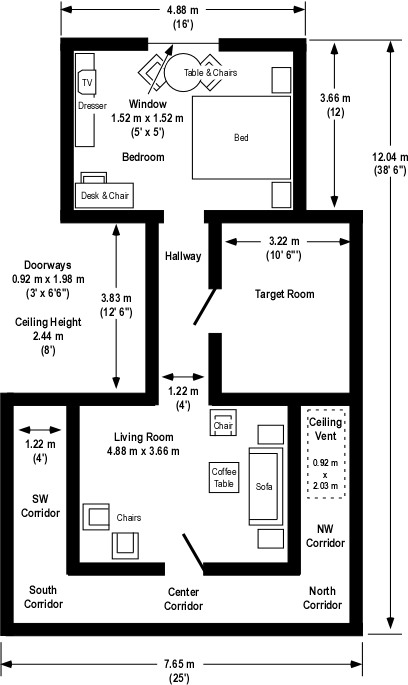

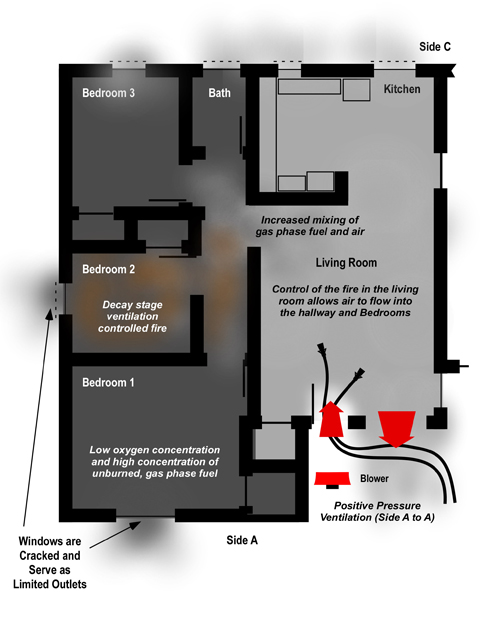

Figure 1. Fire Development in Bedroom 2

Hypothesis

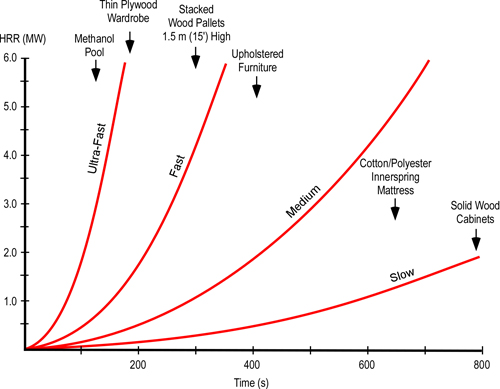

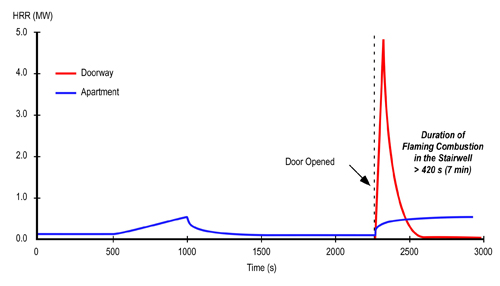

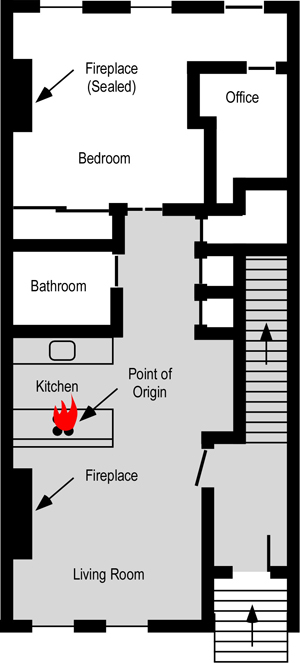

The fire originated in Bedroom 2, likely on or near the bed. In the growth stage, the fire extended through the hallway into the living room (see Figure 1). The fuel load in the living room and ventilation provided by the open front door permitted the fire to progress through flashover and become fully developed (see Figure 2).

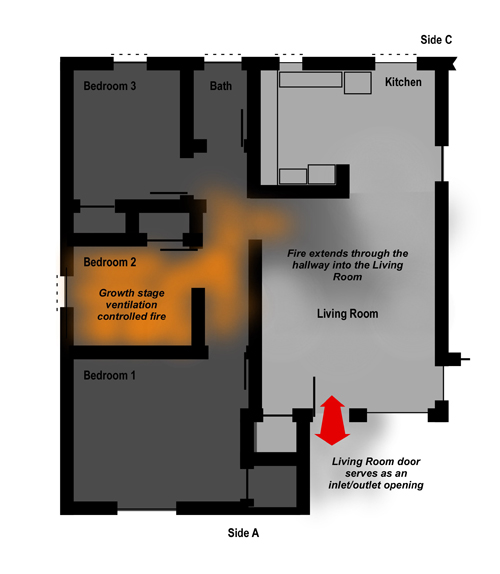

Figure 2. Extension and Fire Development in the Living Room

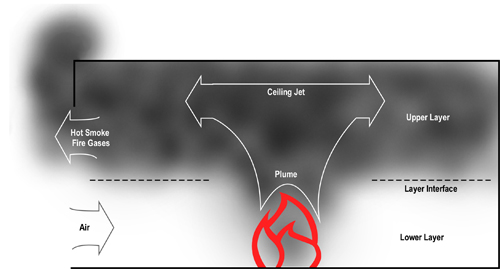

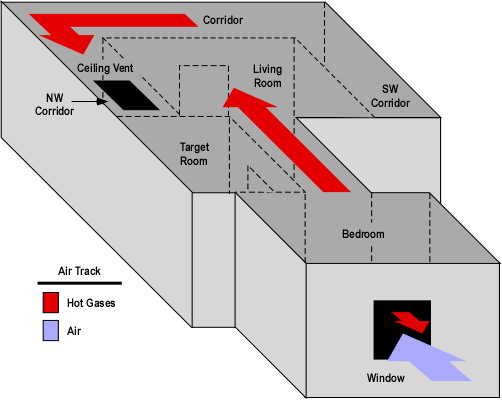

The extent of fire in the living room consumed the oxygen supplied through the front door, resulting in an extremely ventilation controlled fire in the hallway and bedroom. Unburned flammable products of combustion and pyrolysis products from contents and structural materials accumulated in the upper layer in the bedrooms and hallway.

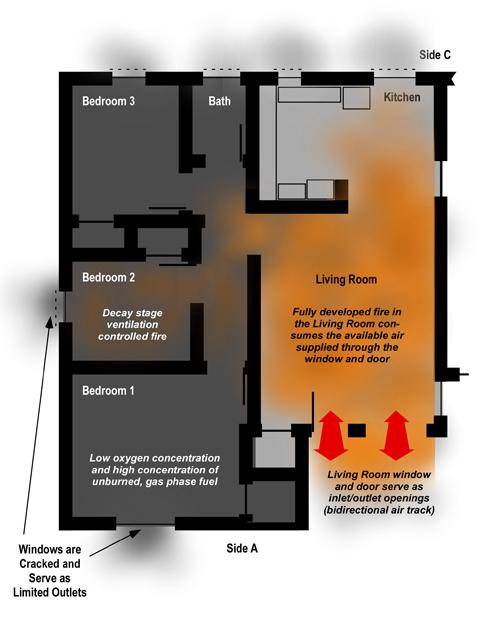

Figure 3. Fire Control and Development of a Gravity Current

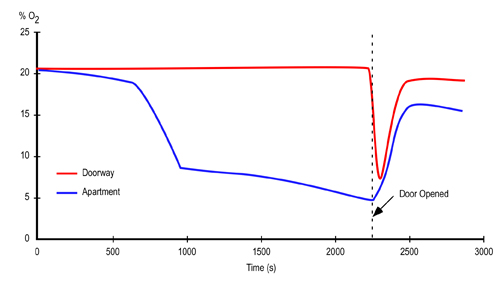

Extinguishment of the fire in the living room allowed development of a gravity current and movement of oxygen through the living room to the hallway and bedrooms allowing flaming combustion in these areas to resume.

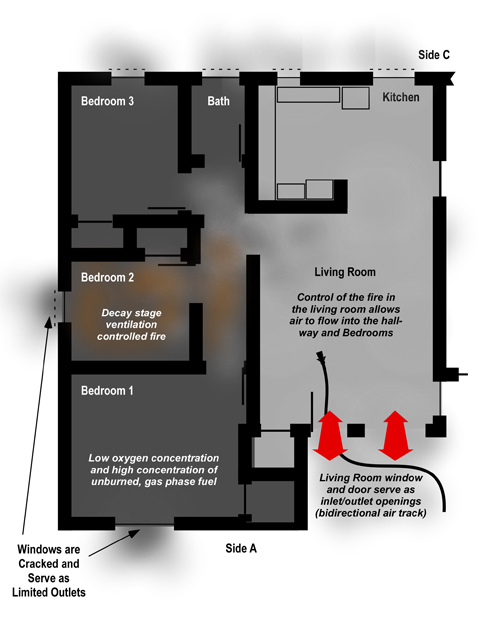

Figure 4. Positive Pressure Ventilation

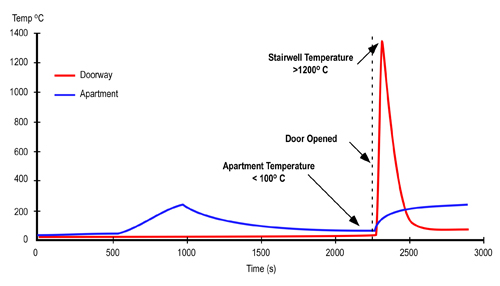

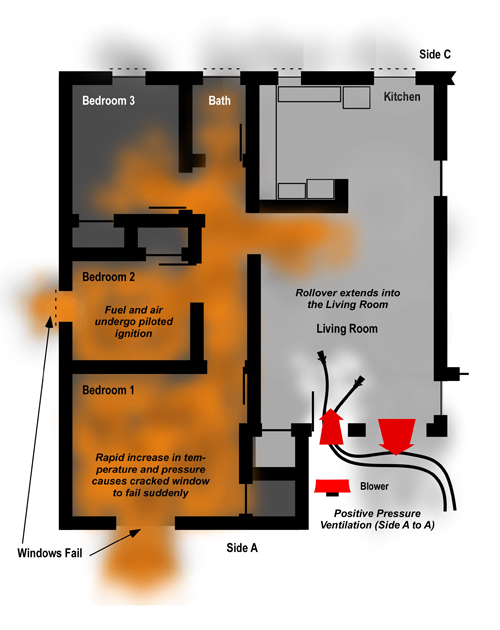

Flaming combustion in the hallway or bedroom resulted in piloted ignition of a substantive accumulation of pyrolysis products and flammable products of incomplete combustion in the upper layer within the hallway and bedrooms. Application of positive pressure at the door on Side A influenced (or speeded up) this phenomena and may have increased the violence of this ignition (due to increased pressure and confinement) but likely aided in limiting the spread of flaming combustion from the hallway into the living room.

Figure 5. Fire Gas Ignition

Supporting Information

Information supporting the preceding hypothesis is divided into three categories: Known, suspected, and assumptions.

Known

The cause and origin and line of duty death investigation conducted by the Contra Costa Fire Protection District and line of duty death investigation conducted by NIOSH identified and documented a range of data supporting this hypothesis. These data elements include physical evidence, and narrative data obtained from interviews with individuals involved in the incident.

- The fuel load in the bedroom included a bed, dresser, and other contents, exposed wood ceiling, carpet, and carpet pad.

- Fire originated in Bedroom 2 (on or near the bed)

- The female occupant exited the structure prior to making a 911 call to report the fire (via cell phone).

- The female occupant then reentered the building prior to the arrival of the first fire unit in an effort to rescue her husband. [Observations by bystanders included in the report]

- The fire in Bedroom 2 entered the growth stage and extended into the hallway and subsequently the living room. This fire spread was in part due to the combustible wood ceiling. [Information on the cause and origin investigation provided in the report]

- Windows other than the living room window on Side A were substantively intact until the occurrence of the extreme fire behavior event. [Observation by firefighters included in the report]

- E70 knocked down the fire in the living room prior to initiating primary search (without a hoseline). E70 used a left hand search pattern in which they would have moved into the hallway and bedrooms located on Side B of the residence.

- A blower was placed at the front door while E70 and E73 were conducting primary search. Due to the placement of the blower close to the door, it is possible that the air cone did not fully cover the door opening. There is no mention in the report regarding the air track at the door or living room window following placement of the blower. However, E73 reported increased visibility and temperature in the kitchen a short time after the blower was placed, and observed rollover from the hallway leading to the bedrooms.]

- The large window in the living room (if fully cleared of glass) would provide approximately equal area as the door on Side A used as an inlet. Given an equal sized inlet and outlet, efficiency of PPV is likely to be approximately 70%. However, given the location of the exhaust opening next to the inlet, the effectiveness of this ventilation at clearing smoke from compartments beyond the living room and kitchen would have been limited.

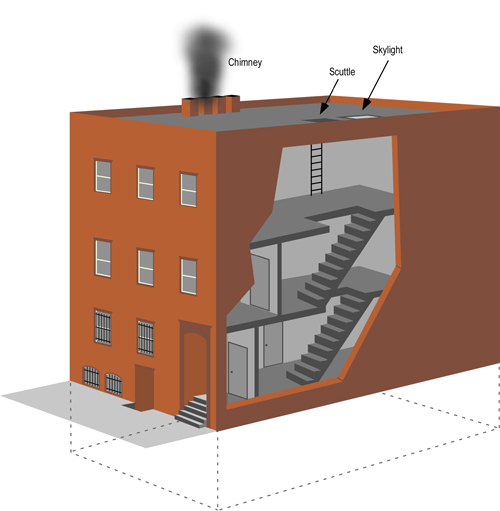

- Vertical ventilation was not completed until after the occurrence of the extreme fire behavior phenomena that trapped and killed Captain Burton and Engineer Desmond. The exhaust opening created in the roof had limited impact on interior conditions when it was completed due to the presence of the original roof.

- Fuel load in this compartment was more than sufficient to provide the heat release rate necessary to allow fire development to flashover. [This assessment is based on post-fire photos, room dimensions, and ventilation openings at the time of the ignition].

- Other bedrooms contained a similar fuel load.

Deductions

Several factors supporting the stated hypothesis are not directly supported by physical evidence or narrative data. These elements are deduced based on the design, construction, and configuration of the building and principles of fire dynamics in conjunction with known information.

- The front door remained open after the female occupant reentered. [E70 reported fire and smoke showing from the door and living room window on arrival, but no information provided in the report regarding the position of the door or extent to which the window had failed (fully or partially)]

- Use of the blower is likely to have increased mixing of air and hot, fuel rich fire gases in the hallway, particularly near the opening between the hallway and the living room. Ventilation of smoke from the living room and kitchen through the window on Side A, likely reduced the potential for flaming combustion to have extended from the hallway into the living room.

- Heat conducted through the tongue and groove wood roof/ceiling may have resulted in melting and gasification of asphalt roofing which may have been forced through gaps between the planks to add to the gas phase fuel resulting from pyrolysis and incomplete combustion of contents and structural surfaces within the involved compartments.

- The primary source of air for the fire was through the front door and the living room window. The bottom of the doorway was the lowest opening in the building, likely resulting in a bi-directional air track with smoke exiting out the top of the door and air entering at the bottom. While the sill of the living room window was higher than the door, a bi-directional air track likely developed at this opening as well, with the extreme lower portion of the window opening serving as an inlet while the top of the window functioned as an outlet for flames and smoke [No information about air track at the front door was provided in the report.]

- The fire in the living room reached the fully developed stage after the civilian occupant reentered and prior to the arrival of E70 [This deduction is based on the ability of the female occupant to enter and make her way to the kitchen and the presence of flames exiting the door and living room window on Side A when E70 arrived]

Assumptions

In addition to known and deduced information, the hypothesis is based on the following assumptions.

- The fully developed, ventilation controlled fire in the living room substantively utilized the atmospheric oxygen provided by the air entering through the front door, causing the fire in Bedroom 2 and the hallway to enter ventilation controlled decay. The decay stage fire and heat from the hot gas layer present in the hallway and adjacent rooms continued pyrolysis of fuel packages in this area, resulting in accumulation of a substantial concentration of gas phase fuel in the smoke.

- Control of the fully developed fire in the living room reduced oxygen demand from the fire. The bi-directional air track would have continued and gravity current would have increased air supply to the ventilation controlled decay stage fire in the hallway and bedroom(s).

- Establishment of positive pressure ventilation with the door on Side A serving as the inlet (or inlet and outlet) and the living room window serving as an outlet would have cleared smoke from the living room, but would not have influenced smoke movement from the hallway and bedrooms (as quickly).

Validation

Special thanks to Dr. Stefan Svensson of the Swedish Civil Contingencies Agency and Assistant Professor Greg Gorbett of Eastern Kentucky University for serving as critical friends and providing useful feedback in development of this analysis.

This hypothesis is supported by a range of evidence, deductions and assumptions. However, further validation would require use of other methods such as development of a computational fluid dynamics model and small or full scale fire tests.

More to Follow

My next post will examine the potential influence of positive pressure ventilation (PPV) in this incident as well as a broader look at potential hazards when PPV is used incorrectly or under inappropriate circumstances.

Ed Hartin, MS, EFO, MIFireE, CFO

References

Contra Costa County Fire Protection District. (2008). Investigation report: Michele drive line of duty deaths. Retrieved February 13, 2009 from http://www.cccfpd.org/press/documents/MICHELE%20LODD%20REPORT%207.17.08.pdf

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (2009). Death in the line of duty report 2007-28. Retrieved May 5, 2009 from http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/fire/pdfs/face200728.pdf.

National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) (2008) NFPA 821 Standard on fire and Explosion Investigations. Quincy, MA: Author.