NIOSH F2009-11: The Minority Report

Tuesday, May 4th, 2010As a critical friend of the NIOSH Firefighter Fatality Investigation and Prevention Program, I have provided testimony at public hearings and engaged in discussions with NIOSH staff regarding improvement of the quality of information provided in Death in the Line of Duty Reports, particularly in incidents involving extreme fire behavior. In addition, I have provided expert review on a number of Death in the Line of Duty Reports (including F2009-11). The discussion of fire dynamics, fire behavior indicators, and influence of ventilation and wind effects in Report F2009-11 is evidence that this feedback has been heard! I would like to thank Tim Merinar and the other NIOSH staff for their efforts in this area.

However, more work is needed. Just over a year ago, I read a news report about the deaths of Captain James Harlow and Firefighter Damion Hobbs of the Houston Fire Department during operations at a residential fire. I recalled Houston had seen a number of fatalities during structural firefighting over a reasonably short period of time. Curious, I reviewed reports on these incidents developed by NIOSH and the Texas State Fire Marshal’s Office. Seeing some commonality in the circumstances surrounding these incidents, I called a colleague at NIOSH and recommended that the investigation of the incident in which Captain Harlow and Firefighter Hobbs lost their lives, include review of prior incidents (and near miss data if available) to identify underlying causal or contributing factors that may not be evident from examination of a single incident.

While we often want to know the cause of a tragic event, the reality is that it is often much more complicated that we would like. Investigative reports such as those prepared by NIOSH focus a bright light on the what and how, but often leave the question of why hidden in the shadows. Observations and questions in this post are not presented as an indictment of the Houston Fire Department, or to question the commitment and bravery of Captain Harlow and Firefighter Hobbs, but simply to encourage each and every one of us to look more deeply; more deeply at our profession, at our own organizations, and at ourselves.

Epidemiology

Epidemiology is the study of factors affecting the health and illness of populations. Epidemiological research is the foundation of public health intervention and preventative medicine. This research is focused at identifying relationships between exposures and disease or death. Identification of causal relationships between exposures and outcomes is critical. However, correlation does not determine cause, and identification of causality is often complex and tentative.

For the fire service, epidemiological study has and continues to focus on heart disease, stress, and cancer (see USFA, NIOSH Launch Cancer Study). However, these same concepts can be applied to traumatic fatalities as well.

R-Fire 7811 Oak Vista, Houston TX

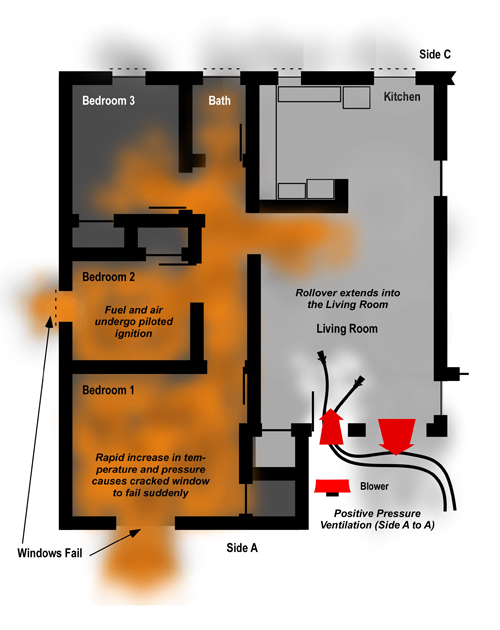

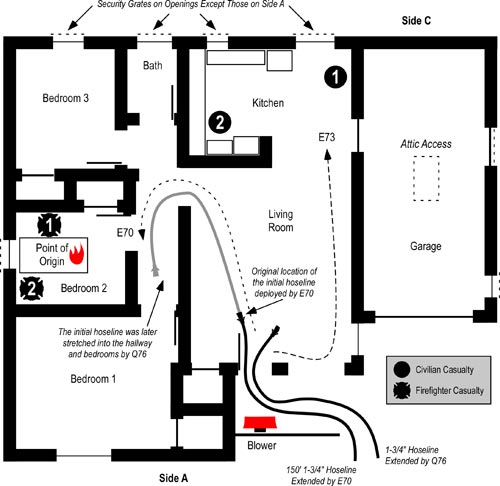

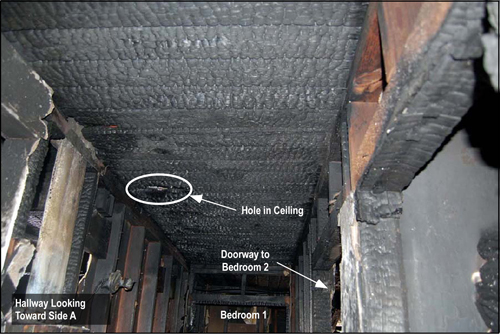

On April 12, 2009 Captain James Harlow and Firefighter Damion Hobbs lost their lives in a residential fire at 7811 Oak Vista in Houston, Texas. On April 9, 2010, the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health released Death in the Line of Duty Report F2009-11 summarizing their investigation of this incident. Overall, this report is well written and provides an excellent examination of the events involved in this incident. The Texas State Fire Marshal’s Office also conducted an investigation of this incident and released a report a short time prior to release of NIOSH Report F2009-11.

- NIOSH Death in the Line of Duty F2009-11

- Texas State Fire Marshal’s Office Firefighter Fatality Investigation FY09-01

Contributing Factors

NIOSH identified eight items as key contributing factors in the deaths of Captain Harlow and Firefighter Hobbs:

- An inadequate size-up prior to committing to tactical operations

- Lack of understanding of fire behavior and fire dynamics

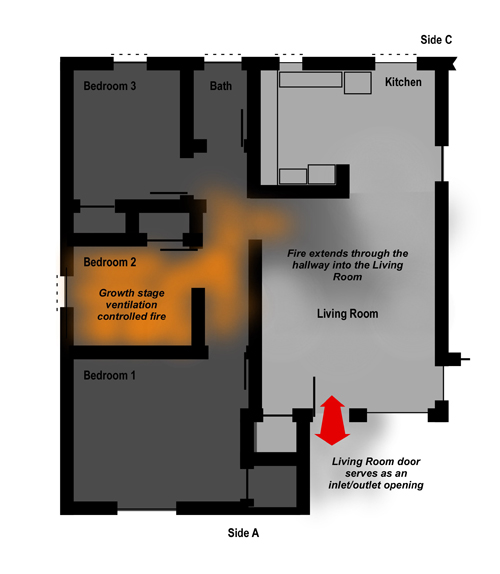

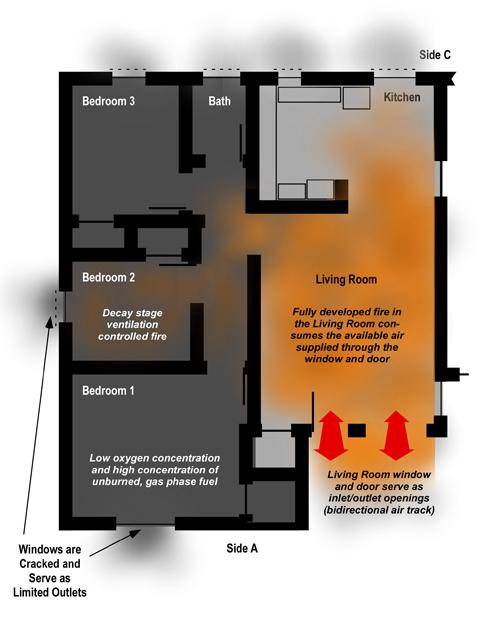

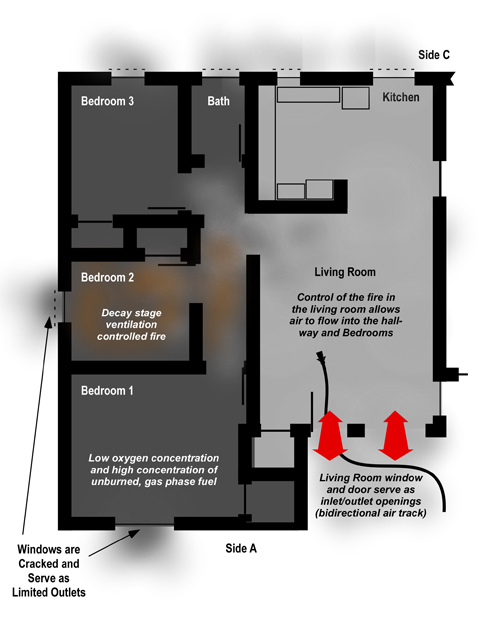

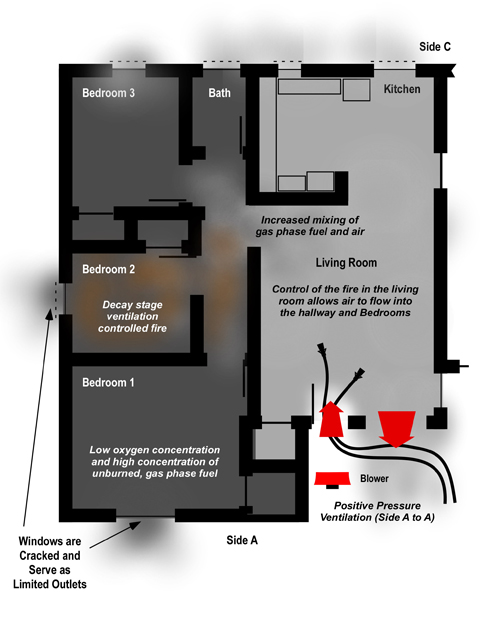

- Fire in a void space burning in a ventilation controlled regime

- High winds

- Uncoordinated tactical operations, in particular fire control and tactical ventilation

- Failure to protect the means of egress with a backup hose line

- Inadequate fireground communications

- Failure to react appropriately to deteriorating conditions.

What is missing from this list? Six of the seven items on this list relate to human action or inaction. The report points out the need for policy, procedures, and additional training to address the contributing factors. While this is undoubtedly necessary, does this provide the entire answer?

The Remaining Question

As with all NIOSH firefighter fatality investigations, the focus of this report is on the circumstances and events surrounding a single incident. In this report, there is a brief mention of investigation of the deaths of other firefighters from this department, but no analysis of commonality or underlying contributing factors is provided. This leaves the question, to what extent did organizational culture impact on the circumstances and events involved in this tragic incident?

In his keynote presentation at the 2010 Fire Department Instructor’s Conference, Lieutenant Frank Ricci of the New Haven (CT) Fire Department indicated that the culture of the fire service is wrongly blamed for many of it’s problems. Lieutenant Ricci indicated that a large percentage of firefighter injuries and deaths are not due to inherent risks, but to an “unwillingness to take personal responsibility for safety” (Thompson, 2010). I would ask, why are firefighters unwilling to take personal responsibility? What factors influence this pattern of behavior? I suspect that it is our unquestioned assumptions about the way that things are (part of our culture). In this sense, culture is not to blame, but is simply one of a number of contributing and causal factors in many firefighter fatalities.

Common Elements

A cursory examination of the facts presented in the reports of NIOSH investigation of traumatic fatalities in the Houston Fire Department since 2000 shows a distinct pattern. Each of the fatalities involved members of the first arriving company where a fast attack was initiated without adequate size up and in most (and likely all) cases failure to assess risk versus gain. A more detailed examination of these events would likely provide a more finely grained picture of organizational expectations that make extremely aggressive fire attack without adequate size-up and risk assessment the norm, rather than the exception.

Table 1. Traumatic Line-of-Duty-Deaths in Houston, Texas 2000-2009

| Report | Event Type | Commonality | ||

| F2000-13 | Collapse (2 LODD) Commercial Fire-Collapse |

Victims were part of first in company

Inadequate size-up Failure to assess risk versus gain |

||

| F2001-33 | Rapid Fire Progress (1 LODD) High-Rise Apartment Fire-Wind Driven Fire |

Victim was part of the first in company

Inadequate size-up (consideration of wind) |

||

| F2004-14 | Rapid Fire Progress (1 LODD) Commercial Fire-Disorientation Subsequent to Rapid Fire Progress |

Victim was part of the first in company

Inadequate size-up Failure to assess risk versus gain |

||

| F2005-09 | Collapse & Rapid Fire Progress (1 LODD) Residential Fire (Vacant)-Rapid Collapse Subsequent to Fire Progress | Victim was part of the first in company

Inadequate size-up Failure to assess risk versus gain |

||

| F2009-11 | Rapid Fire Progress (2 LODD) Residential Fire-Wind Driven Fire | Victim was part of the first in company

Inadequate size-up Failure to assess risk versus gain |

A Comparison

On September 11, 1991, Continental Express Flight 2574 crashed in Eagle Lake Texas killing all 14 people aboard. As with all commercial aircraft accidents, this incident was investigated by the National Transportation Safety Board. The board identified the cause as failure of maintenance and inspection personnel to adhere to proper maintenance and quality assurance procedures. However, the board also identified failure of management to ensure compliance with approved procedures and failure of Federal Aviation Administration to detect and correct this problem as contributing factors. Board member John K. Lauber, filed a dissenting statement. “It is clear based on this record alone, that the series of failures which led directly to the accident were not the result of an aberration, but rather resulted from the normal accepted way of doing business at Continental Express” (NTSB, 1992, p. 53). Lauber advocated restating the probable cause of this accident as “the failure of Continental Express management to establish a corporate culture which encouraged and enforced adherence to approved maintenance and quality assurance procedures” (NTSB, 1992, p. 54).

It is essential to look at the five events identified in reports F2000-13, F2001-33, F2004-14, F2005-09, and F2009-11 (NIOSH, 2001, 2002, 2005a, 2005b, 2010) from a longitudinal perspective to identify in greater detail and understand the common elements and potential systemic cultural issues that influenced the actions of those involved. While the influence of organizational culture is more difficult to identify than failure to comply with good practice, failure to recognize a hazardous condition, or an error in decision-making, it has a far more pervasive influence on fire fighter safety than these specific, individual acts.

Based on limited research, it is apparent that the Houston Fire Department (like many others) places an extremely high value on rapid and aggressive offensive firefighting operations. While the outcome of this incident resulted from a wide range of interrelated contributing factors, organizational culture and lack of knowledge regarding fire behavior and the influence of tactical operations were likely the most significant.

Identification of organizational culture as a contributing factor in this incident is based on data included in the DRAFT report as well as review of NIOSH Reports F2000-13, F2001-33, F-2004-14, F2005-09, and F2009-11 (NIOSH, 2001, 2002, 2005a, 2005b, 2010) as well as review of the Houston Fire Department Strategic Plan FY2008-2012 (n.d., HFD) and Philosophy of Firefighting (2003, HFD).

A memorandum from the Office of the Fire Chief defining the Houston Fire Department’s philosophy of firefighting (HFD, 2003) after the McDonald’s (NIOSH, 2001) and Four Leaf Tower (NIOSH, 2002) fires reinforced the importance of risk assessment in selecting strategies and tactics. In this memo, the chief identified the importance of organizational culture, stating “we pride ourselves in being very aggressive interior fire fighters and look down on those that fight fire from the street” (p. 1). While this memorandum was written in 2003, lack of adequate size up and risk assessment was a contributing factor in three incidents resulting in four line-of-duty deaths involving Houston Fire Department members in subsequent six years.

The Houston Fire Department Strategic Plan for FY2008-2012 (n.d., HFD) identifies safety as a core organizational value, stating: “preservation of life remains the number one goal of the HFD beginning with the responder and extending to the public” (p. 5). This focus continues with enhancement of the health and safety of HFD members as the first goal within the strategic plan. However, while the strategic plan provides a detailed blueprint for action, no objective or action plan element addresses the predominant contributory factors that are common in the seven line-of-duty deaths of Houston Fire Department members resulting from traumatic cause between 1999 and 2009. For example, Objective 1.5 of the strategic plan focuses on National Fallen Fire fighter Initiative #1 which states “define and advocate the need for cultural change within the fire service relating to safety; incorporating leadership, management, supervision, accountability and personal responsibility (HFD, n.d., p. 8). However, the sub elements of this objective focus on near miss reporting, roadway emergency safety, and response to violent incidents.

In the incident that took the lives of Captain Harlow and Firefighter Hobbs, several elements point to the focus on speed and aggressive action. Despite his seniority and experience, the captain of the first arriving engine quickly initiated an interior attack without adequate size-up and risk assessment (or performed a size-up and failed to recognize critical fire behavior indicators). In addition, he left his portable radio on the apparatus, E-26s thermal imaging camera (TIC) was left outside the front door. Any one of these elements alone might indicate a simple error, but in combination along with the context provided by previous LODD incidents (NIOSH, 2001, 2002, 2005a, 2005b) this is likely evidence of the cultural value of speed and aggressive action over deliberate assessment of conditions and decision-making based on risk assessment.

While increased protection through the use of the reed hood has significant potential benefits (similar technology is used by the Swedish fire service), it is quite possible that this type of personal protective clothing (which is somewhat unique to the Houston Fire Department) is used to permit fire fighters to penetrate deeper into hostile environments, rather than simply to provide improved protection with the ordinary or hazardous range of conditions encountered during structural firefighting.

Recommendation

Based on these factors identified in NIOSH Report F2009-11 (2010) as well Reports F2000-13, F2001-33, F2004-14, F2005-09 (2001, 2002, 2005a, 2005b), I recommend that fire service organizations assess the impact of their organizational culture on fire fighter safety and operational performance.

Note that this recommendation is not simply focused on the Houston Fire Department. It is a global recommendation, that each of us examine the influence of culture within our respective organizations.

Ed Hartin, MS, EFO, MIFireE, CFO

References

Houston Fire Department. (2003) Philosophy of firefighting. Retrieved January 24, from http://www.houstontx.gov/fire/reports/philoff.pdf

Houston Fire Department. (n.d.) Houston Fire Department Strategic Plan FY2008-2012. Retrieved January 24 from http://www.houstontx.gov/fire/reports/SP0811.pdf

National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB). Aircraft accident report: Britt Airways, Inc. d/b/a/ Contenental Express Flight 2474 in flight structural breakup, EMB-120RT, N33701, Eagle Lake, Texas, September 11, 1991, NTSB/AAR-92/04. Washington, DC: Author.

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). (2001). Death in the line of duty, Report F2000-13. Retrieved January 24, 2010 from http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/fire/pdfs/face200013.pdf.

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). (2002). Death in the line of duty, Report F2001-33. Retrieved January 24, 2010 from http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/fire/pdfs/face200133.pdf.

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). (2005a). Death in the line of duty, Report F2004-14. Retrieved January 24, 2010 from http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/fire/pdfs/face200414.pdf.

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). (2005b). Death in the line of duty, Report F2005-09. Retrieved January 24, 2010 from http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/fire/pdfs/face200509.pdf.

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). (2010). Death in the line of duty, Report F2009-11. Retrieved April 25, 2010 from http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/fire/pdfs/face200911.pdf

Thompson, J. (2010) FDIC keynote: Fire service culture not to blame for problems. Retrieved May 3, 2010 from http://www.firerescue1.com/firefighter-safety/articles/810852-FDIC-keynote-Fire-service-culture-not-to-blame-for-problems/