Positive Pressure Ventilation:

Inadequate Exhaust

Thursday, May 21st, 2009

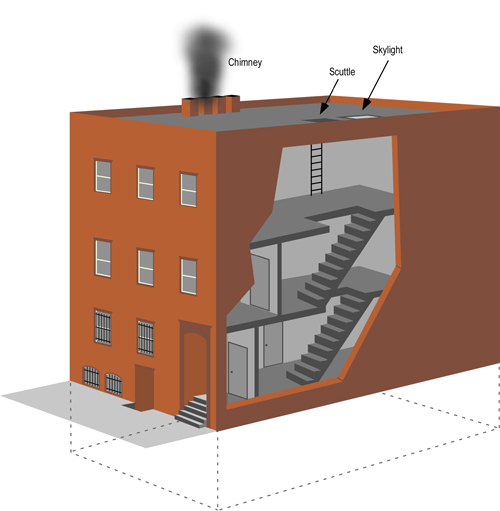

As discussed in my last post, lack of an adequate exhaust opening is a common factor when use of positive pressure ventilation causes or increases the severity of extreme fire behavior. Unfortunately there has not been a great deal of research examining why this is the case. Part of the challenge in conducting a scientific investigation of this issue is the tremendous variability in building configuration and fire conditions. Control of these variables becomes more difficult as building configuration becomes more complex and multiple fire scenarios are considered. However, this does not preclude improvement of our understanding of this important issue.

Burning Regime

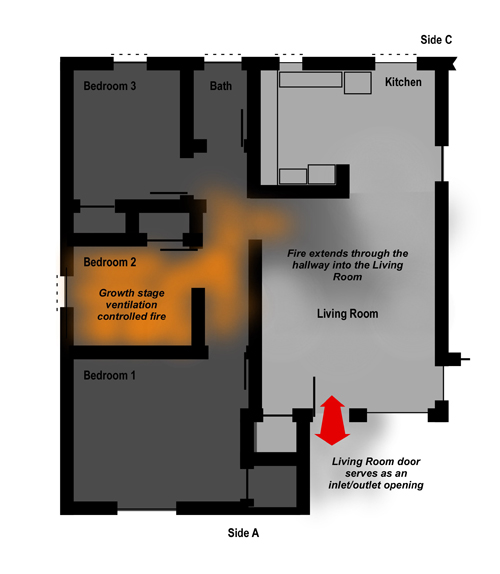

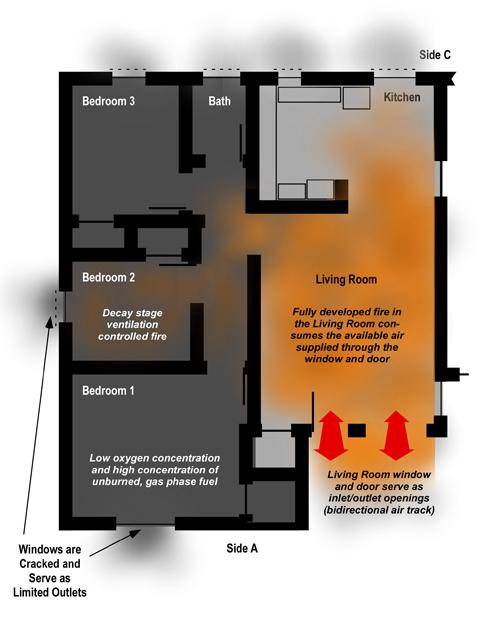

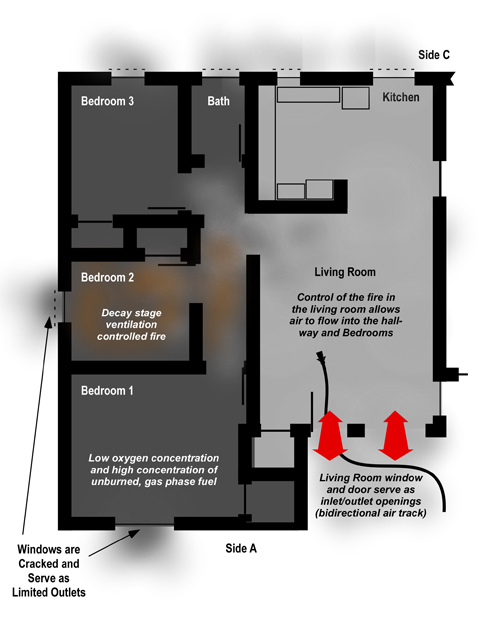

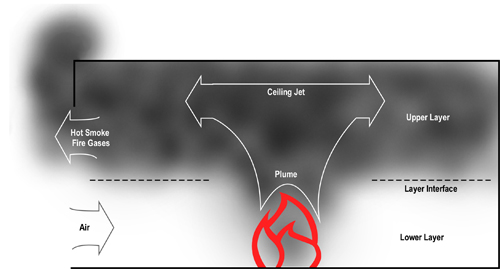

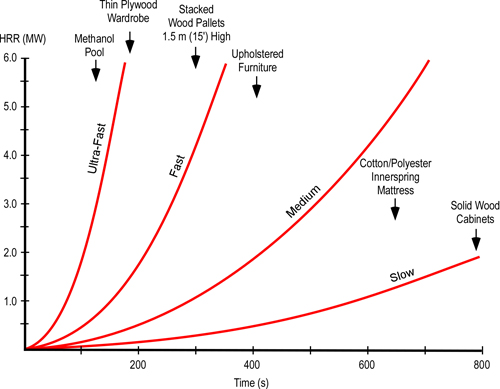

How an increase in ventilation influences fire behavior is largely (but not entirely) dependent on burning regime. If the fire is fuel controlled, fire development is dependent on the characteristics, configuration and amount of fuel. When a compartment fire becomes ventilation controlled, fire development is limited by the available oxygen. In the ventilation controlled burning regime, increased ventilation results in increased heat release rate. See my earlier post Fuel and Ventilation for additional information on burning regime.

In most ventilation controlled fires, the concentration of gas phase fuel (i.e., unburned pyrolyzate and flammable products of incomplete combustion) is not sufficient to present threat of backdraft. In these cases, increased ventilation will generally result in one of the following outcomes:

- Increase in heat release rate that is not sufficient to result in a rapid transition to a fully developed fire (flashover)

- Rapid increase in heat release rate that results in flashover and a fully developed fire.

- Intervention by firefighters to control the fire before ventilation induced flashover can occur.

If the concentration of gas phase fuel is sufficient to present threat of backdraft, increased ventilation may result in a backdraft…or not (depending on the extent of mixing of air and smoke, presence of an adequate ignition source, etc.).

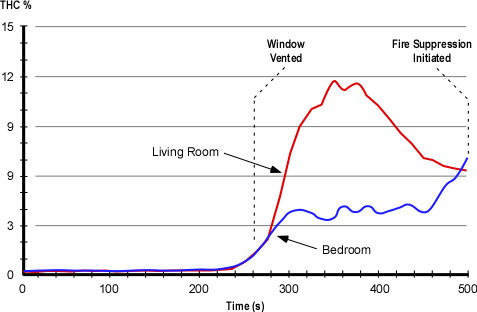

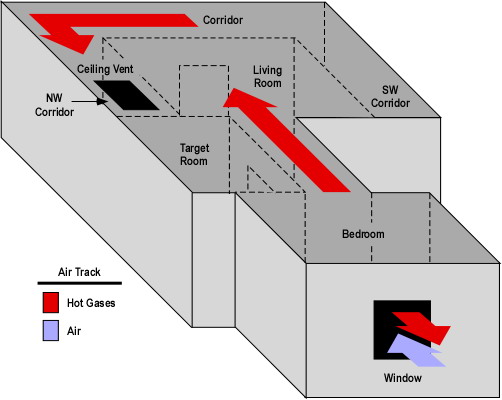

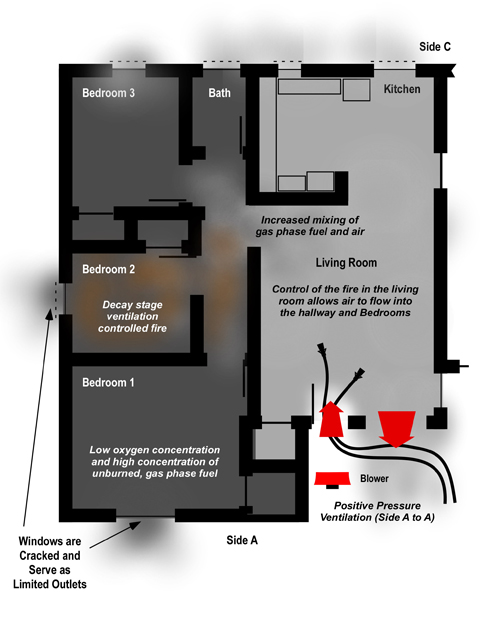

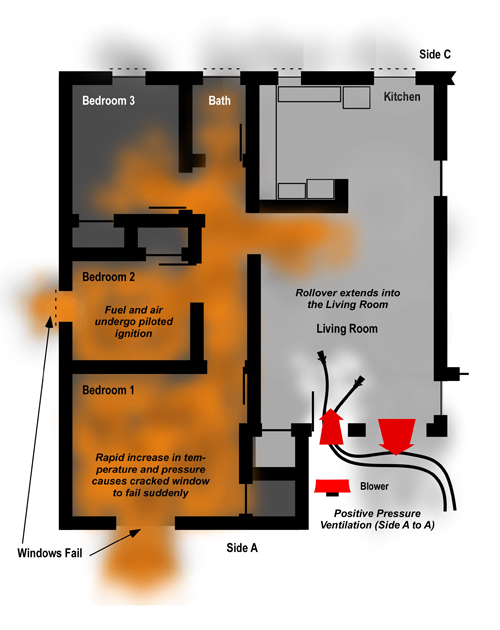

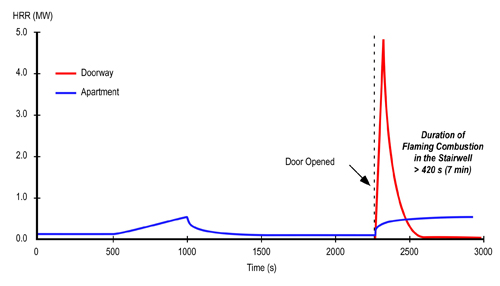

The greater the extent to which the fire is ventilation controlled and the higher the concentration of gas phase fuel, the greater the potential for extreme fire behavior following increases in ventilation. Positive pressure ventilation influences this process in several ways, if effective, gas phase fuel is removed from the structure (often burning outside the exhaust opening). If PPV is not effective, increased air flow is accompanied with turbulence and resultant mixing of fuel an air which increases the probability of ignition and rapid fire progression. In addition, pressure applied at the outlet increases confinement which may increase the violence of extreme fire behavior phenomena such as backdraft.

Fluid Dynamics

Movement of fluids (liquids and gases) should be of significant interest to firefighters. Both fireground hydraulics and tactical ventilation require an understanding of fluid dynamics. In examining the influence of inadequate exhaust opening size on the effectiveness of PPV and potential for extreme fire behavior, I found some parallels with fireground hydraulics.

Laminar Flow: Smooth movement of a fluid in parallel layers with little disruption between the layers. The following video clip illustrates laminar flow in a pipe.

Turbulent Flow: Fluid flow characterized by eddies and vortexes disrupting smooth movement. The following video clip illustrates turbulent flow in a pipe.

A number of characteristics influence flow characteristics when a fluid moves through a conduit such as a pipe, hoseline, or even a building. These include fluid characteristics such as viscosity and density, the roughness of the conduit, restrictions to flow, and velocity of the fluid.

For example, friction loss in 1-1/2″ (38 mm) hose is higher than that in 1-3/4″ (45 mm) hose at the same flow rate. Why? Velocity must be higher to move the same flow rate through the smaller hose. This results in increased turbulence and resulting loss in pressure. If a discharge gate is partially closed, this obstructs the waterway, creating turbulence and increasing friction loss. As illustrated in this example, increased velocity and the presence of obstructions both increase turbulence. How does this apply to PPV?

The extent of turbulence as air and fire effluent (smoke and fire gases) move through a building is influenced by the configuration of the building (e.g., walls, doorways), obstructions (e.g., furniture), and velocity. Turbulence increases mixing of fire effluent and air. If the concentration of unburned pyrolizate and flammable products of incomplete combustion is high, turbulence increases the potential of a flammable mixture. In addition, increased oxygen concentration and air movement across surfaces can result in transition from surface to flaming combustion, providing a source of ignition for the flammable mixture of fire effluent and air.

Outlet/Inlet Ratio

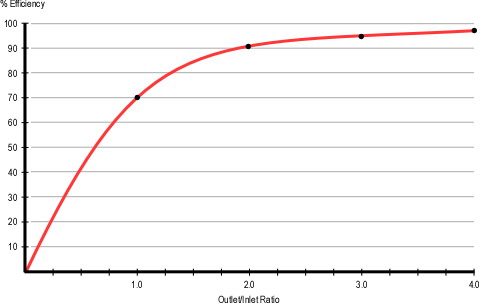

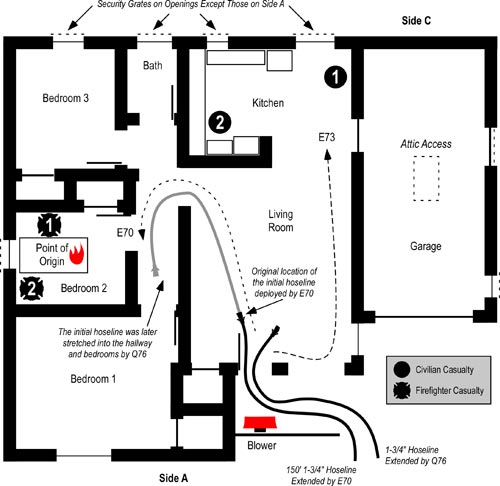

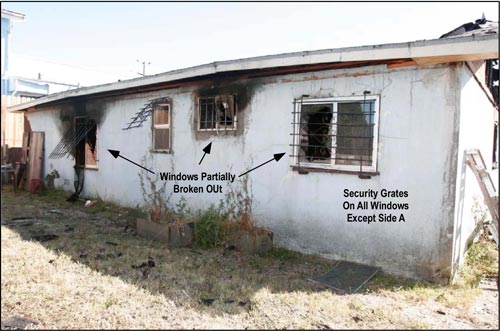

When using natural ventilation, the size of the inlet opening(s) should be larger than the exhaust opening(s). However, with positive pressure ventilation this is reversed. When using PPV. exhaust opening(s) should be at least as large and preferably two to three times as large as the inlet opening as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. PPV Efficiency Curve

Note: Adapted from Fire Ventilation (Svensson, 2000, p. 71)

For a detailed examination of the physics and mathematical explanation of how the positive pressure ventilation efficiency curve is derived, see Stefan Svensson’s excellent text Fire Ventilation.

If the outlet size is adequate, a unidirectional ventilation flow from inlet to outlet is created. If opening size is inadequate, turbulence is increased as fire effluent and air seeks an exit path. If no opening is made or if the opening is extremely small, fire effluent may push back out the inlet opening.

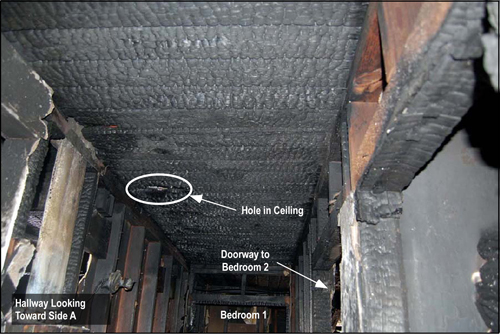

Watch the following video clip and focus your attention on the exhaust opening on Side B (at approximately 0:19) and fire behavior indicators immediately after the blower is placed at the door on Side A and started (at approximately 3:00)

Find more videos like this on firevideo.net

Even though there was an exhaust opening, it was of inadequate size. While this fire was likely progressing towards a ventilation induced flashover due to the effects of natural horizontal ventilation, increased airflow and turbulence caused by ineffective PPV likely was a contributing factor in the way that this extreme fire behavior phenomena occurred.

Important: Implementation of PPV after entry and before the fire has been located and controlled presents a significant risk to firefighters. Risk can be minimized by either using positive pressure attack (implementing PPV prior to entry) or locating and controlling the fire before implementing PPV.

Next Steps

In the Education vs. Training in Fire Space Control, Kris Garcia (2008) wrote that we need to increase our focus on ventilation education, rather than simply training on ventilation skills. Effective use of PPV to support fire attack or following fire control requires an understanding of fire and fluid dynamics as well as skill in creating openings and the placement and operation of blowers.

My next post will examine review Positive Thinking, an article by Watch Manager Gary West of the Lancashire Fire Rescue Service (UK) published in the August 2008 issue of Fire Risk Management. In this article, Gary provides an excellent overview of the approach to PPV training and implementation taken by the UK fire service.

References

Svensson, S. (2005). Fire ventilation. Karlstad, Sweden: Swedish Rescue Services Agency.

Garcia, K. (2008, September). Education vs. training in fire space sontrol. Fire Engineering. Retrieved May 21, 2009 from http://positivepressureattack.com/images/pdfs/EdVsTng-GarciaFESept08.pdf

West, G. (2008, August). Positive thinking. Fire Risk Management, 46-49.

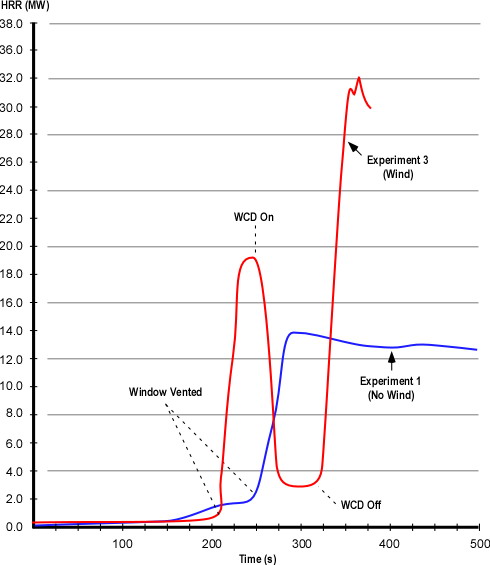

Note: Adapted from Firefighting Tactics Under Wind Driven Conditions.

Note: Adapted from Firefighting Tactics Under Wind Driven Conditions.