Developing Door Control Doctrine

Monday, June 17th, 2013Door Control Doctrine

As discussed in my last post, doctrine is a guide to action rather than a set of rigid rules. Clear and effective doctrine provides a common frame of reference, helps standardize operations, and improves readiness by establishing a common approach to tactics and tasks. Doctrine should link theory, history, experimentation, and practice to foster initiative and creative thinking.

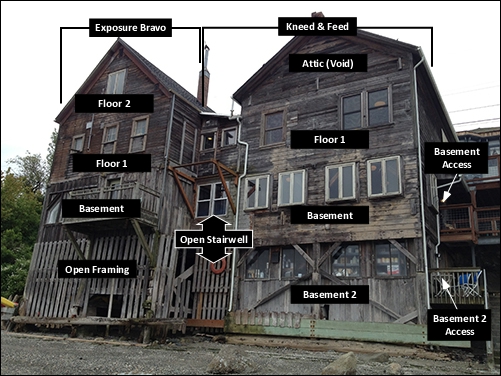

One way to frame the discussion necessary to develop doctrine that is applicable to a range of circumstances, is to use a series of scenarios presenting different conditions and examine what is similar and what is different. Ideally, firefighters will work together to integrate this theoretical discussion with their experience to develop sound doctrine based on their own context (e.g., staffing, building and occupancy types).

Fireground Scenarios

Important! Not all of the tactics presented in the questions are appropriate and others may be appropriate in one context, but not necessarily in another. For example, a lightly staffed engine may not have the option of offensive operations until the arrival of additional resources (barring a known imminent life threat), where a company with greater staffing may have greater strategic and tactical flexibility. These questions focus on the impact of strategic (offensive or defensive) tactical options on fire dynamics.

Scenario 1: The first arriving company arrives to find a small volume of smoke showing from around windows and doors and from the eaves on Side Alpha with low velocity, no air inlet is obvious. Performing a 360o reconnaissance, the officer observes similar smoke and air track indicators on other sides of the building and that all doors and windows are closed. Several windows on Side Alpha (Alpha Bravo Corner) are darkened with condensed pyrolysis products and the home appears to have smoke throughout (smoke logged).

How do you think the fire will develop between arrival and initiation of offensive fire attack (assuming that adequate resources are on-scene for offensive operations) assuming no change in ventilation prior to fire attack.

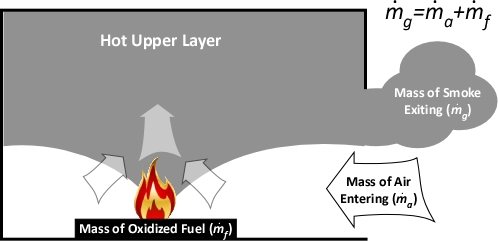

The fire is likely in a ventilation controlled, decay stage. If the ventilation profile does not change prior to entry (e.g., doors are kept closed, windows remain intact), the heat release rate (HRR) from the fire will continue to decline and temperatures within the building will drop (but may still be fairly high when entry is made).

How would opening the front door prior to having a charged line at the doorway on Side Alpha impact fire development?

Increased ventilation will result in a significant and potentially rapid increase in HRR. The proximity of the door to the fire compartment and temperature in the fire compartment at the time that ventilation is increased will have a direct impact on the speed with which the fire returns to the growth stage (but still remaining ventilation controlled). The closer the air inlet to the fire and the higher the temperature, the more rapidly the fire will return to the growth stage.

How would horizontal ventilation of the fire compartment (Alpha/Bravo Corner) impact fire development if performed as soon as the hoseline is deployed to the (still closed) doorway on Side Alpha?

As noted in the answer to question 2, increased ventilation will result in an increase in HRR. As windows in the fire compartment are in closer proximity to the fire, taking the windows potentially will result in a more rapid return to the growth (but still ventilation controlled) stage. It is also important to consider that a window cannot be unbroken; selecting this ventilation option does not provide an option for changing you mind if you do not like the result.

What would be the impact on fire behavior if the engine company advanced the first hoseline to the windows; took the glass and applied water to the burning fuel inside the fire compartment prior to making entry through the door? How might this change if offensive fire attack was delayed (e.g., insufficient staffing for offensive operations)?

This is an interesting question! Research by UL, NIST, and FDNY has shown the positive impact of exterior application of water into the fire compartment in reducing heat release rate. However, as noted in the answer to the preceding question, a window cannot be unbroken. If this is simply a contents fire in the compartment where the window is broken and water is applied, the result is likely to be favorable with a temporary reduction in HRR due water applied on burning fuel. However, if the fire extended to other areas of the building which shielded from direct attack at this point of application, effectiveness of exterior application from this single location is likely to be limited.

How would opening the front door and horizontal ventilation of the fire compartment (Alpha/Bravo Corner) impact fire development if performed as soon as the hoseline is deployed to the doorway on Side Alpha?

Advice on coordination of tactical ventilation and fire attack has typically stated, don’t vent until a charged hoseline is in place. This is good advice, but requires a bit of clarification.

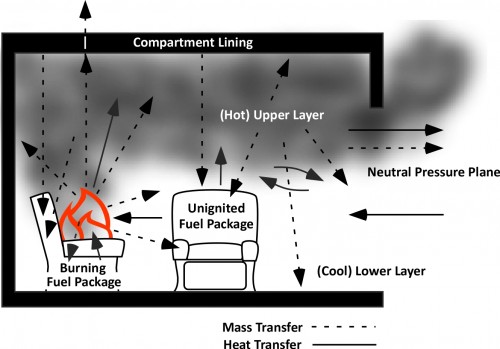

“As soon as the hoseline is deployed to the doorway” may simply mean that a dry line has been stretched and firefighters are donning their self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA) facepieces while waiting for water. The fire will begin transition back to the growth stage as soon as tactical ventilation is performed. Depending on the time required for the firefighters to mask up, the line to be charged, air bled off, pattern checked, and the charged line advanced to the fire compartment(s), the HRR may increase significantly and conditions are likely to be quite a bit worse than if the door and window had remained closed until the hoseline was in place to begin offensive fire attack from the interior.

If tactical ventilation is performed after the line is charged and firefighters are ready to immediately make entry and quickly advance to the fire compartment, it is likely that the effect of increased ventilation will be positive. There may be some increase in HRR, but it is likely to be minimal due to the short distance and simple stretch from the front door to the fire compartment(s). Once direct attack has begun to control the fire, the increased ventilation will improve conditions inside the building.

Assuming that sufficient resources are on-scene to permit an offensive attack, when should the entry point be opened? Assuming that the door is unlocked, how should the fire attack crew approach this task?

Tactical size-up is critical for the crew assigned to offensive fire attack. This includes assessment of B-SAHF (Building, Smoke, Air Track, Heat, and Flame) indicators, forcible entry requirements, and assessment of fire attack requirements (e.g., flow rate, length of line, and complexity of the stretch).

The door should remain closed until the crew on the hoseline is ready to make entry; hoseline charged, air bled off, nozzle function and pattern checked, SCBA facepeices on, on-air. Check to see if the door is unlocked, but control the door (closed) and check conditions inside (visible fire, level of the hot upper layer, presence of victims inside the doorway) by opening the door slightly. The firefighter on the nozzle should do this check while the tools firefighter opens and controls the door. If hot smoke or flames are evident, the nozzle firefighter should cool the upper layer with one or more pulses of water fog (depending on conditions). The door should be closed while the crew assesses the risk of entry (e.g., floor is intact and fire conditions will permit entry from this location). If OK for entry; the crew can open the door and advance the line inside, while cooling the upper layer as necessary.

See Nozzle Techniques & Hose Handling: Part 3 for additional information on door entry procedure.

Once the hoseline is deployed into the building through the door on Side Alpha for offensive fire attack, should the door remain fully open or closed to the greatest extent possible? Why?

Ideally, the door will be closed after the hoseline is advanced through the doorway to limit the air supplied to the fire. How this is accomplished will depend on staffing. The door may be controlled by the fire attack crew or it may be controlled by the standby crew (two-out).

As discussed in the prior post Influence of Ventilation in Residential Structures: Tactical Implications Part 2, when the door is open, the clock is ticking! In the ventilation controlled burning regime, increased ventilation results in an increasing HRR as the fire returns to the growth stage. The timeframe for increased HRR is dependent on the proximity of the inlet to the fire, configuration of the building, and temperature in the fire area (higher temperature results in faster increase in HRR). Closing the door (even partially) slows the increase in HRR. Once the attack line begins direct attack, the door can be opened as part of planned, systematic, and coordinated tactical ventilation.

Assuming that this is a contents fire and horizontal ventilation will be appropriate, when and where should it be performed (describe the flow path from inlet to exhaust)?

As with most questions, the answer here is “it depends”. There are a few missing bits of information that are important to horizontal tactical ventilation. Wind direction and the location of potential openings. To keep things simple, assume that there is no wind and that the only potential openings in the fire compartment are two windows on Side Alpha at the Alpha/Bravo Corner.

Once direct attack has commenced, horizontal tactical ventilation can be performed from Alpha (doorway) to Alpha (windows in the fire compartment). As the top of the door and tops of the windows are likely to be approximately at the same level, there a bi-directional flow path (smoke out at the top and air in at the bottom) is likely to develop. However, the bottom of the door is lower than the windows which will provide increased air movement from the door to the fire compartment.

In discussing this question (and the entire topic of door control for that matter), some firefighters will undoubtedly raise the question of positive pressure attack (PPA) or positive pressure ventilation (PPV). These tactics may provide an effective approach in this scenario, but developing comprehensive tactical ventilation doctrine requires examination of all of the options to control both smoke and air movement, so we are starting with a look at anti-ventilation and tactical ventilation using natural means.

Scenario 2: The first arriving company arrives to find smoke showing with moderate velocity and a bi-directional air track (smoke out the top and air in the bottom) from an open door on Side Alpha. A moderate volume of smoke is also pushing from around windows and from the eaves on Side Alpha. Several windows on Side Alpha (Alpha Bravo Corner) are darkened with condensed pyrolysis products and a glow is visible inside in the room behind these windows. Performing a 360o reconnaissance, the officer observes similar smoke and air track indicators on other sides of the building and that all doors and windows with the exception of the door on Side Alpha are closed. Returning to Side Alpha, the officer observes that the velocity of smoke from the open door has increased and flames at the interface between the smoke and air as it exits the doorway. The home appears to have smoke throughout (smoke logged).

How do you think the fire will develop between arrival and initiation of offensive fire attack (assuming that adequate resources are on-scene for offensive operations) assuming no change in ventilation prior to fire attack.

The fire is in a ventilation controlled burning regime (indicators include the limited ventilation provided by the single opening at the front door and flames at the interface between the smoke and air at the door). The open door will likely provide sufficient ventilation for the fire to continue its growth and extension from the compartment of origin along the flowpath to the front door.

How would the officer closing the front door prior to having a charged line at the doorway on Side Alpha (e.g., when performing the 360) impact fire development?

Based on the reported observations during 360o reconnaissance, the only significant ventilation opening is the front door. The bi-directional air track indicates that this opening is serving as both an inlet and outlet. Closing the door will reduce the air supply to the fire and will reduce the HRR and slow worsening conditions outside the fire compartment. Ideally this would be done prior to starting the 360o reconnaissance.

Assuming that sufficient resources are on-scene to permit an offensive attack and the door was closed during the 360, when should the entry point be opened? How should this task be approached?

As in Scenario 1, the door should be opened only when the crew on the hoseline is ready to make entry; hoseline charged, air bled off, nozzle function and pattern checked, SCBA facepeices on, on-air. The same door entry procedure described in Scenario 1 should be used as if the door had been closed on arrival.

How would horizontal ventilation of the fire compartment (Alpha/Bravo Corner) impact fire development is performed as soon as the hoseline is deployed to the open doorway on Side Alpha?

The outcome of tactical ventilation of the fire compartment will depend on sequence and timing. If the door remained open during initial size-up and while the line was being stretched, he fire would have continued to grow (limited by ventilation provided by the doorway and interior configuration of the building). Additional ventilation in this case would result in a rapid increase in HRR. If the door had been closed during the 360, the increase in HRR on ventilation of the windows would likely be somewhat slower as the HRR and temperature in the fire compartment would have dropped once the door was closed. In either case, HRR will increase while the charged line is being stretched from the entry point to the fire compartment. This is not necessarily a problem if the stretch is quick and the flow rate of the hoseline is adequate. It is essential that the crews stretching the line and performing ventilation understand the influence of their actions on fire behavior and are not surprised at the result.

Once the hoseline is deployed into the building through the door on Side Alpha for offensive fire attack, should the door remain fully open or closed to the greatest extent possible? Why?

As noted in Scenario 1, closing the door to the greatest extent possible after the line is inside will slow fire development until the hoseline is in place to begin a direct attack.

Assuming that this is a contents fire and horizontal ventilation will be appropriate, when and where should it be performed (describe the flow path from inlet to exhaust)?

The same basic approach would be taken as in Scenario 1. Once direct attack has commenced, horizontal tactical ventilation can be performed from Alpha (doorway) to Alpha (windows in the fire compartment).

Scenario 3: The first arriving company arrives to find smoke showing with moderate velocity and a bi-directional air track (smoke out the top and air in the bottom) from an open door on Side Alpha. A moderate volume of smoke is also pushing from around windows and from the eaves on Side Alpha. Flames are visible from several windows on Side Alpha (Alpha Bravo Corner) with a bi-directional air track (flames from the upper ¾ of the window with air entering the lower ¼). Performing a 360o reconnaissance, the officer observes similar smoke and air track indicators on other sides of the building and that all doors and windows with the exception of the two windows and door on Side Alpha are closed. Returning to Side Alpha, the officer observes that the velocity of smoke from the open door has increased and flames at the interface between the smoke and air as it exits the doorway. Flames from the windows on Side Alpha are similar to when first observed. The home appears to have smoke throughout (smoke logged).

How do you think the fire will develop between arrival and initiation of offensive fire attack (assuming that adequate resources are on-scene for offensive operations) assuming no change in ventilation prior to fire attack.

The fire is likely in a ventilation controlled burning regime (indicators include the limited ventilation provided by the openings at the front door and windows. Existing ventilation will likely be sufficient for the fire to continue its growth and extension from the compartment of origin along the flowpath to the front door. As there are multiple ventilation openings (more cross sectional area), HRR is greater and as a result fire development and spread will be much more rapid than in Scenario 2.

How would the officer closing the front door prior to having a charged line at the doorway on Side Alpha (e.g., when performing the 360) impact fire development?

As the windows in the fire compartment have failed and are serving as ventilation openings (in addition to the front door), the fire will likely remain in a ventilation controlled growth stage even if the door is closed. However, closing the door will still reduce the air supply to the fire and will slow fire growth. In addition, elimination of the flow path between the fire compartment and front door will reduce heat transfer along this flow path.

Assuming that sufficient resources are on-scene to permit an offensive attack and the door was closed during the 360, when should the entry point be opened? How should this task be approached?

As in Scenarios 1 and 2, the door should be opened only when the crew on the hoseline is ready to make entry; hoseline charged, air bled off, nozzle function and pattern checked, SCBA facepeices on, on-air. The same door entry procedure described in the prior scenarios should be used.

How would horizontal ventilation of the fire compartment (Alpha/Bravo Corner) impact fire development if performed as soon as the hoseline is deployed to the open doorway on Side Alpha?

As the windows in the fire compartment have already failed, some ventilation of the fire compartment has already occurred. In that the fire is ventilation controlled, any additional ventilation will significantly increase HRR. With a ventilation controlled growth stage fire and high temperature in the fire compartment, the HRR will increase rapidly.

Once the hoseline is deployed into the building through the door on Side Alpha for offensive fire attack, should the door remain fully open or closed to the greatest extent possible? Why?

As in the previous two scenarios, the door should be closed to as great an extent possible after the hoseline is advanced inside the building. This will limit air to the fire, slow fire development, an reduce the flow path between the fire and the front door.

Assuming that this is a contents fire and horizontal ventilation will be appropriate, when and where should it be performed (describe the flow path from inlet to exhaust)?

As the windows in the fire compartment have already failed, they will continue to provide ventilation. Once a direct attack has been initiated, the front door may be opened to increase air flow and the efficiency of the horizontal ventilation from Side Alpha to Side Alpha.

As noted in the previous post, these questions were all based on a similar fire (different development based on the ventilation profile at the time of the first company’s arrival) in the same, simple building, a one story, wood frame dwelling. It is important to examine other levels of involvement and ventilation profiles in this building as well as other types of buildings and fire conditions with similar questions. Also give some thought to the impact of door control when using vertical ventilation in coordination with fire attack.

Additional Examples

The following video of pre-arrival conditions and initial fireground operations provides an additional opportunity to consider the impact of ventilation and the importance of door control.

Video 1: In the first video, the door is closed when the fire department arrives, but the fire has self-vented through a window on Side Delta.

How might effective door control have influenced fire development and the safety of companies operating at this incident?

Video 2: In this video, the front door is open when the fire department arrives and it appears that the fire may have self-vented on Side Charlie.

How might effective door control have influenced fire development and the safety of companies operating at this incident?

Video 3: In the last video, the front door is partially open and existing ventilation includes a window on Side Alpha and one or more openings on Side Charlie.

How might effective door control have influenced fire development and the safety of companies operating at this incident?

My next post will come back to the final set of questions regarding door control doctrine posed in Close the Door! Where You Born in a Barn?