Townhouse Fire: Washington, DC

What Happened

Monday, September 14th, 2009

This post continues study of an incident that resulted in two line-of-duty deaths as a result of extreme fire behavior in a townhouse style apartment building in Washington, DC.

A Quick Review

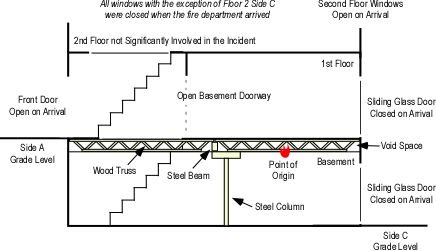

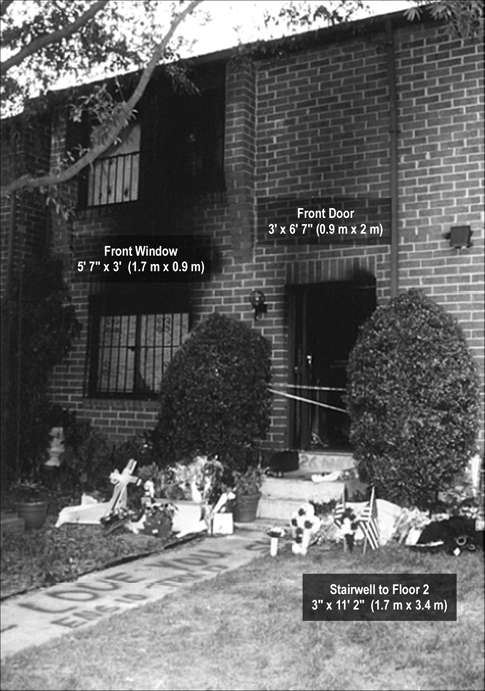

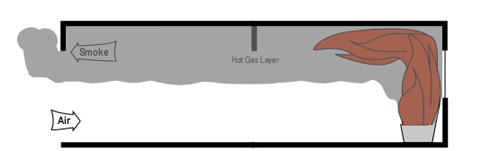

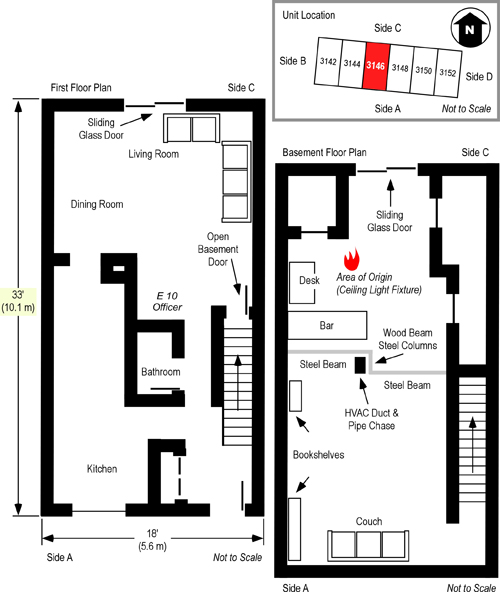

The previous post in this series, Fire Behavior Case Study of a Townhouse Fire: Washington, DC examined building construction and configuration that had a significant impact on the outcome of this incident. The fire occurred in the basement of a two-story, middle of building, townhouse style apartment with a daylight basement. This configuration provided an at grade entrance to the Floor 1 on Side A and an at grade entrance to the Basement on Side C.

The fire originated in an electrical junction box attached to a fluorescent light fixture in the basement ceiling (see Figures 1 and 2). The occupants of the unit were awakened by a smoke detector. The female occupant noticed smoke coming from the floor vents on Floor 2. She proceeded downstairs and opened the front door and then proceeded down the first floor hallway towards Side C, but encountered thick smoke and high temperature. The female and male occupants exited the structure, leaving the front door open, and made contact with the occupant of an adjacent unit who notified the DC Fire & EMS Department at 0017 hours.

Dispatch Information

At 00:17, DC Fire & EMS Communications Division dispatched a first alarm assignment consisting of Engines 26, 17, 10, 12, Trucks 15, 4, Rescue Squad 1, and Battalion 1 to 3150 Cherry Road NE. At 0019 Communications received a second call, reporting a fire in the basement of 3146 Cherry Road NE. Communications transmitted the update with the change of address and report of smoke coming from the basement. However, only one of the responding companies (Engine 26) acknowledged the updated information.

Weather Conditions

Temperature was approximately 66o F (19o C) with south to southwest winds at 5-10 mi/hr (8-16 km/h), mostly clear with no precipitation.

Conditions on Arrival

Approaching the incident, Engine 26 observed smoke blowing across Bladensburg Road. Engine 26 arrived at a hydrant at the corner of Banneker Drive and Cherry Road at 00:22 hours and reported smoke showing. A short time later, Engine 26 provided an updated size-up with heavy smoke showing from Side A of a two story row house. Based on this report, Battalion 1 ordered a working fire dispatch and a special call for the Hazmat Unit at 00:23. This added Engine 14, Battalion 2, Medic 17 and EMS Supervisor, Air Unit, Duty Safety Officer, and Hazmat Unit.

Firefighting Operations

DC Fire and EMS Department standard operating procedures (SOP) specify apparatus placement and company assignments based on dispatch (anticipated arrival) order. Note that dispatch order (i.e., first due, second due) may de different than order of arrival if companies are delayed by traffic or are out of quarters.

Standard Operating Procedures

Operations from Side A

The first due engine lays a supply line to Side A, and in the case of basement fires, the first line is positioned to protect companies performing primary search on upper floors by placing a line to cover the interior stairway to the basement. The first due engine is backed up by the third due engine. The apparatus operator of the third due engine takes over the hydrant and pumps supply line(s) laid by the first due engine, while the crew advances a backup line to support protection of interior exposures and fire attack from Side A.

The first due truck takes a position on Side A and is responsible for utility control and placement of ladders for access, egress, and rescue on Side A. If not needed for rescue, the aerial is raised to the roof to provide access for ventilation.

The rescue squad positions on Side A (unless otherwise ordered by Command) and is assigned to primary search using two teams of two. One team searches the fire floor, the other searches above the fire floor. The apparatus operator assists by performing forcible entry, exterior ventilation, monitoring search progress, and providing emergency medical care as necessary.

Operations from Side C

The second due engine lays a supply line to the rear of the building (Side C), and in the case of basement fires, is assigned to fire attack if exterior access to the basement is available and if it is determined that the first and third due engines are in a tenable position on Floor 1. The second due engine is responsible for checking conditions in the basement, control of utilities (on Side C), and notifying Command of conditions on Side C. Command must verify that the first and third due engines can maintain tenable positions before directing the second due engine to attack basement fires from the exterior access on Side C.

The second due truck takes a position on Side C and is responsible for placement of ladders for access, egress, and rescue on Side C. The aerial is raised to the roof to provide secondary access for ventilation (unless other tasks take priority).

Command and Control

The battalion chief positions to have an unobstructed view of the incident (if possible) and uses his vehicle as the command post. On greater alarms, the command post is moved to the field command unit.

Notes: This summary of DC Fire & EMS standard operating procedures for structure fires is based on information provided in the reconstruction report and reflects procedures in place at the time of the incident. DC Fire & EMS did not use alpha designations for the sides of a building at the time of this incident. However, this approach is used here (and throughout the case) to provide consistency in terminology.

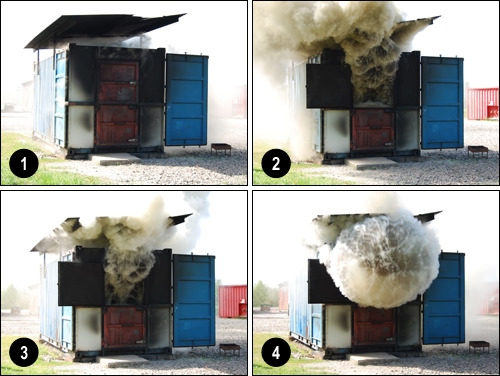

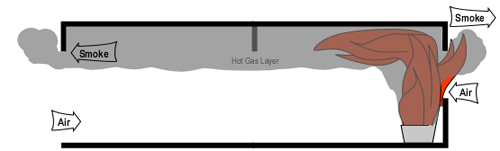

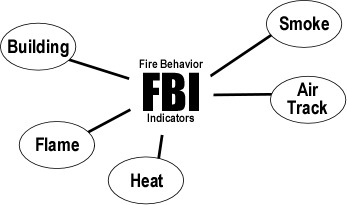

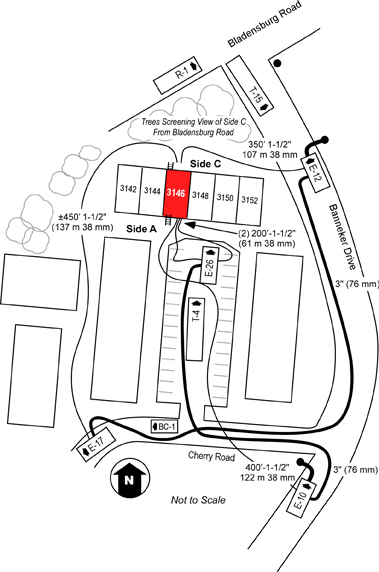

First due, Engine 26 laid a 3″ (76 mm) supply line from a hydrant at the intersection of Banneker Drive and Cherry Road NE, positioned in the parking lot on Side A, and advanced a 200′ 1-1/2″ ( 61 m 38 mm) pre-connected hoseline to the first floor doorway of the fire unit on Side A (see Figures 1 and 2). A bi-directional air track was evident at the door on Floor 1, Side A , with thick (optically dense) black smoke from the upper area of the open doorway. Engine 26’s entry was delayed due to a breathing apparatus facepiece malfunction. The crew of Engine 26 (Firefighters Mathews and Morgan and the Engine 26 Officer) made at approximately 00:24.

Figure 1. Plot and Floor Plan-3146 Cherry Road NE

Note: Adapted from Report from the Reconstruction Committee: Fire at 3146 Cherry Road NE, Washington DC, May 30, 1999, p. 18 & 20. District of Columbia Fire & EMS, 2000; Simulation of the Dynamics of the Fire at 3146 Cherry Road NE, Washington D.C., May 30, 1999, p. 12-13, by Daniel Madrzykowski & Robert Vettori, 2000. Gaithersburg, MD: National Institute of Standards and Technology, and NIOSH Death in the Line of Duty Report 99 F-21, 1999, p. 19.

Engine 10, the third due engine arrived shortly after Engine 26, took the hydrant at the intersection of Banneker Drive and Cherry Road, NE, and pumped Engine 26’s supply line. After Engine 10 arrived at the hydrant, the firefighter from Engine 26 who had remained at the hydrant proceeded to the fire unit and rejoined his crew. Engine 10, advanced a 400′ 1-1/2″ (122 m 38 mm) line from their own apparatus as a backup line. Firefighter Phillips and the Engine 10 officer entered through the door on Floor 1, Side A (see Figure 2) while the other member of their crew remained at the door to assist in advancing the line.

Truck 15, the first due truck arrived at 00:23 and positioned on Side A in the parking lot behind Engine 26. The crew of Truck 15 began laddering Floor 2, Side A, and removed kitchen window on Floor 1, Side A (see Figure 2). Due to security bars on the window, one member of Truck 15 entered the building and removed glass from the window from the interior. After establishing horizontal ventilation, Truck 15 accessed the roof via a portable ladder and began vertical ventilation operations.

Engine 17, the second due engine, arrived at 00:24, laid a 3″ (76 mm) supply line from the intersection of Banneker Drive and Cherry Road NE, to a position on Cherry Road NE just past the parking lot, and in accordance with department procedure, stretched a 350′ 1-1/2″ (107 m 38 mm) line to Side C (see Figure 2).

Approaching Cherry Road from Banneker Drive, Battalion 1 observed a small amount of fire showing in the basement and assigned Truck 4 to Side C. Battalion 1 parked on Cherry Road at the entrance to the parking lot, but was unable to see the building, and proceeded to Side A and assumed a mobile command position.

Second due, Truck 4 proceeded to Side C and observed what appeared to be a number of small fires in the basement at floor level (this was actually flaming pieces of ceiling tile which had dropped to the floor). The officer of Truck 4 did not provide a size-up report to Command regarding conditions on Side C. Truck 4, removed the security bars from the basement sliding glass door using a gasoline powered rotary saw and sledgehammer. After clearing the security grate Truck 4, broke the right side of the sliding glass door to ventilate and access the basement (at approximately 00:27) and then removed the left side of the sliding glass door. The basement door on Side C was opened prior to Engine 17 getting a hoseline in place and charged. After opening the sliding glass door in the basement, Truck 4 attempted to ventilate windows on Floor 2 Side C using the tip of a ladder. They did not hear the glass break and believing that they had been unsuccessful; they left the ladder in place at one of the second floor windows and continued with other tasks.

Figure 2. Location of First Alarm Companies and Hoselines

Note: Adapted from Report from the Reconstruction Committee: Fire at 3146 Cherry Road NE, Washington DC, May 30, 1999, p. 27. District of Columbia Fire & EMS, 2000.

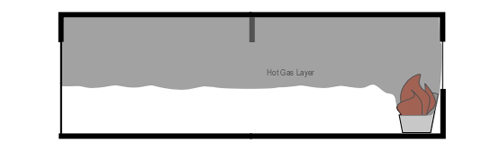

Unknown to Truck 4, these windows had been left open by the exiting occupants. Truck 4B (two person team from Truck 4) returned to their apparatus for a ladder to access the roof from Side C. Rescue 1 arrived at 00:26 and reported to Side C after being advised by the male occupant that everyone was out of the involved unit (this information was not reported to Command). Rescue 1 and Truck 4 observed inward air track (smoke and air) at the exterior basement doorway on Side C and an increase in the size of the flames from burning material on the floor.

Engines 26 and 10 encountered thick smoke and moderate temperature as they advanced their charged 1-1/2″ (38 mm) hoselines from the door on Side A towards Side C in an attempt to locate the fire. As they extended their hoselines into the living room, the temperature was high, but tolerable and the floor felt solid. It is important to note that engineered, lightweight floor support systems such as parallel chord wood trusses do not provide reliable warning of impending failure (e.g., sponginess, sagging), failure is often sudden and catastrophic (NIOSH, 2005; UL, 2009).

Prior to reaching Side C of the involved unit, Engine 17 found that their 350′ 1-1/2″ (107 m 38 mm) hoseline was of insufficient length and needed to extend the line with additional hose.

Engine 12, the fourth arriving engine, picked up Engine 17’s line, completed the hoselay to a hydrant on Banneker Drive (see Figure 2). The crew of Engine 12 then advanced a 200′ 1-1/2″ (61 m 38 mm) hoseline from Engine 26 through the front door of the involved unit on Side A and held in position approximately 3′ (1 m) inside the doorway. This tactical action was contrary to department procedure, as the fourth due engine has a standing assignment to stretch a backup line to Side C.

Rescue 1’s B Team (Rescue 1B) and a firefighter from Truck 4 entered the basement without a hoseline in an effort to conduct primary search and access the upper floors via the interior stairway. Engine 17 reported that the fire was small and requested that Engine 17 apparatus charge their line.

Questions

Consider the following questions related to the interrelationship between strategies, tactics, and fire behavior:

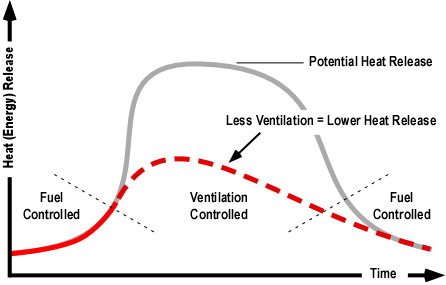

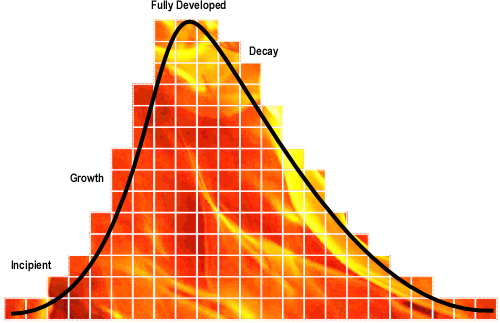

- Based on the information provided to this point, what was the stage of fire development and burning regime in the basement when Engine 26 entered through the door on Floor 1, Side A? What leads you to this conclusion?

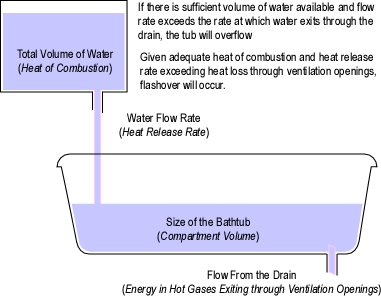

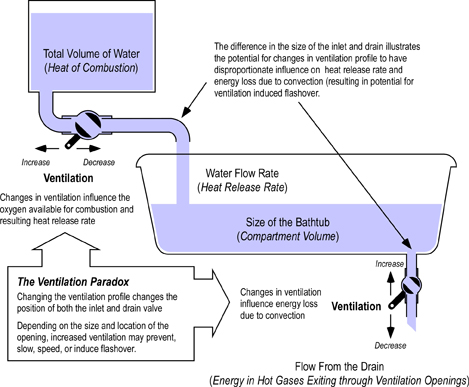

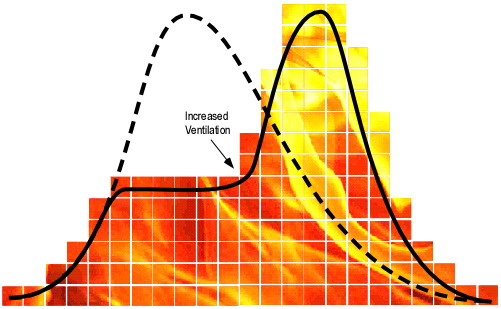

- What impact do you believe Truck 4’s actions to open the Basement door on Side C will have on the fire burning in the basement? Why?

- What is indicated by the strong inward flow of air after the Basement door on Side C is opened? How will this change in ventilation profile impact on air track within the structure?

- Did the companies at this incident operate consistently with DC Fire & EMS SOP? If not, how might this have influenced the effectiveness of operations?

- Committing companies with hoselines to the first floor when a fire is located in the basement may be able to protect crews conducting search (as outlined in the DC Fire & EMS SOP). However, what building factors increased the level of risk of this practice in this incident?

More to Follow

My next post will examine the extreme fire behavior phenomena that trapped Firefighters Phillips, Mathews, and Morgan and efforts to rescue them.

Remember the Past

This week marked the anniversary of the largest loss of life in a line-of-duty death incident in the history of the American fire service. Each September, we stop and remember the sacrifice made by those 343 firefighters. However, it is also important to remember and learn from events that take the lives of individual firefighters. In an effort to encourage us to remember the lessons of the past and continue our study of fire behavior, each month I include brief narratives and links to NIOSH Death in the Line of Duty reports and other documentation in my posts.

September 9, 2006

Acting CAPT Vincent R. Neglia

North Hudson Regional Fire & Rescue Department, NJ

Captain Neglia and other firefighters were dispatched to a report of fire in a three-story apartment building in Union City. Upon their arrival at the scene, firefighters found light smoke and no visible fire. Based on reports that the structure had not been evacuated, Captain Neglia and other firefighters entered the building to perform a search. Due to the light smoke conditions, Captain Neglia was not wearing his facepiece.

Captain Neglia was the first firefighter to enter an apartment. Conditions deteriorated rapidly as fire in the cockloft broke through a ceiling . Captain Neglia was trapped by rapid fire progress and subsequent collapse. Other firefighters came to his aid and removed him from the building. Captain Neglia was transported to the hospital but later died of a combination of smoke inhalation and burns.

NIOSH did not investigate and prepare a report on the incident that took the life of Captain Neglia.

Ed Hartin, MS, EFO, MIFireE, CFO

References

District of Columbia (DC) Fire & EMS. (2000). Report from the reconstruction committee: Fire at 3146 Cherry Road NE, Washington DC, May 30, 1999. Washington, DC: Author.

Madrzykowski, D. & Vettori, R. (2000). Simulation of the Dynamics of the Fire at 3146 Cherry Road NE Washington D.C., May 30, 1999, NISTR 6510. August 31, 2009 from http://fire.nist.gov/CDPUBS/NISTIR_6510/6510c.pdf

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). (1999). Death in the line of duty, Report 99-21. Retrieved August 31, 2009 from http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/fire/reports/face9921.html

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). (2005). NIOSH Alert: Preventing Injuries and Deaths of Fire Fighters Due to Truss System Failures. Retrieved August 31, 2009 from http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/fire/reports/face9921.html