Influence of Ventilation in Residential Structures: Tactical Implications Part 5

The fifth tactical implication identified in the Underwriters Laboratories study of the Impact of Ventilation on Fire Behavior in Legacy and Contemporary Residential Construction (Kerber, 2011) is described as failure of the smoke layer to lift following horizontal natural ventilation and smoke tunneling and rapid air movement in through the front door.

In the experiments conducted by UL, both the single and two story dwellings filled rapidly with smoke with the smoke layer reaching the floor prior to ventilation. This resulted in zero visibility throughout the interior (with the exception of the one bedroom with a closed door). After ventilation, the smoke layer did not lift (as many firefighters might anticipate) as the rapid inward movement of air simply produced a tunnel of clear space just inside the doorway.

Put in the context of the Building, Smoke, Air Track, Heat, and Flame (B-SAHF) fire behavior indicators, these phenomena fit in the categories of smoke and air track. Why did these phenomena occur and what can firefighters infer based on observation of these fire behavior indicators?

Smoke Versus Air Track

There are a number of interrelationships between Smoke and Air Track. However, in the B-SAHF organizing scheme they are considered separately. As we begin to develop or refine the map of Smoke Indicators it is useful to revisit the difference between these two categories in the B-SAHF scheme.

Smoke: What does the smoke look like and where is it coming from? This indicator can be extremely useful in determining the location and extent of the fire. Smoke indicators may be visible on the exterior as well as inside the building. Don’t forget that size-up and dynamic risk assessment must continue after you have made entry!

Air Track: Related to smoke, air track is the movement of both smoke (generally out from the fire area) and air (generally in towards the fire area). Observation of air track starts from the exterior but becomes more critical when making entry. What does the air track look like at the door? Air track continues to be significant when you are working on the interior.

Smoke Indicators

There are a number of smoke characteristics and observations that provide important indications of current and potential fire behavior. These include:

- Location: Where can you see smoke (exterior and interior)?

- Optical Density (Thickness): How dense is the smoke? Can you see through it? Does it appear to have texture like velvet (indicating high particulate content)?

- Color: What color is the smoke? Don’t read too much into this, but consider color in context with the other indicators.

- Physical Density (Buoyancy): Is the smoke rising, sinking, or staying at the same level?

- Thickness of the Upper Layer: How thick is the upper layer (distance from the ceiling to the bottom of the hot gas layer)?

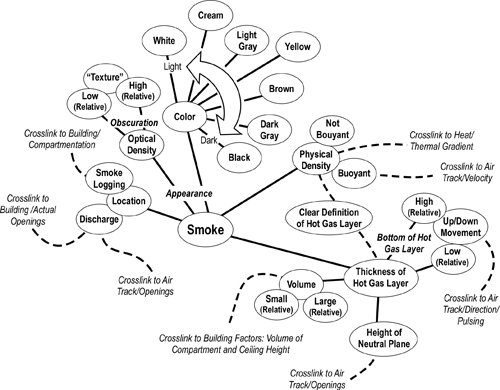

As discussed in Reading the Fire: Smoke Indicators Part 2, these indicators can be displayed in a concept map to show greater detail and their interrelationships (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Smoke Indicators Concept Map

Air Track

Air track includes factors related to the movement of smoke out of the compartment or building and the movement of air into the fire. Air track is caused by pressure differentials inside and outside the compartment and by gravity current (differences in density between the hot smoke and cooler air). Air track indicators include velocity, turbulence, direction, and movement of the hot gas layer.

- Direction: What direction is the smoke and air moving at specific openings? Is it moving in, out, both directions (bi-directional), or is it pulsing in and out?

- Wind: What is the wind direction and velocity? Wind is a critical indicator as it can mask other smoke and air track indicators as well as serving as a potentially hazardous influence on fire behavior (particularly when the fire is in a ventilation controlled burning regime).

- Velocity & Flow: High velocity, turbulent smoke discharge is indicative of high temperature. However, it is essential to consider the size of the opening as velocity is determined by the area of the discharge opening and the pressure. Velocity of air is also an important indicator. Under ventilation controlled conditions, rapid intake of air will be followed by a significant increase in heat release rate.

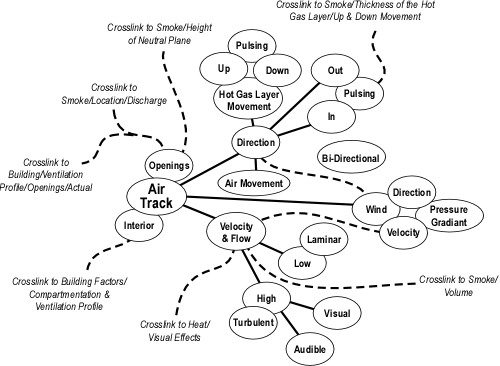

As discussed in Reading the Fire: Air Track Indicators Part 2, these indicators can be displayed in a concept map to show greater detail and their interrelationships (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Air Track Indicators Concept Map

air t

Discharge of smoke at openings and potential openings (Building Factors) is likely the most obvious indicator of air track while lack of smoke discharge may be a less obvious, but equally important sign of inward movement of air. Observation and interpretation of smoke and air movement at openings is an essential part of air track assessment, but it must not stop there. Movement of smoke and air on the interior can also provide important information regarding fire behavior.

An Ongoing Process

Reading the fire is an ongoing process, beginning with reading the buildings in your response area prior to the incident and continuing throughout firefighting operations. It is essential to not only recognize key indicators, but to also note changing conditions. This can be difficult when firefighters and officer are focused on the task at hand.

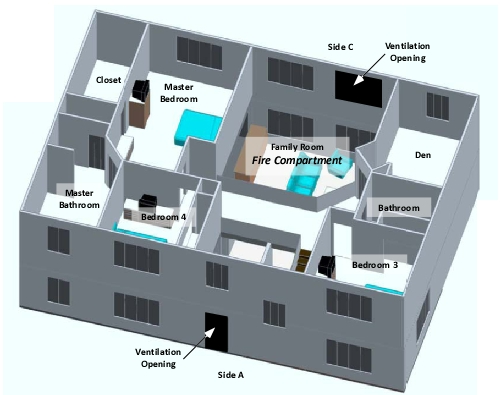

UL Experiment 13

This experiment examined the impact of horizontal ventilation through the door on Side A and one window as high as possible on Side C near the seat of the fire. The family room was the fire compartment. This room had a high (two-story) ceiling with windows at ground level and the second floor level (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Two-Story Dwelling

In this experiment, the fire was allowed to progress for 10:00 after ignition, at which point the front door (see Figure 3) was opened to simulate firefighters making entry. Fifteen seconds after the front door was opened (10:15), an upper window in the family room (see Figure 3) was opened. No suppression action was taken until 12:28, at which point a 10 second application of water was made through the window on Side C using a straight stream from a combination nozzle.

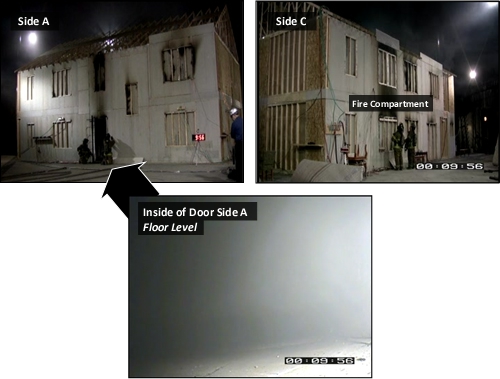

As with all the other experiments in this series fire development followed a consistent path. The fire quickly consumed much of the available oxygen inside the building and became ventilation controlled. At oxygen concentration was reduced, heat release rate and temperature within the building also dropped. Concurrently, smoke and air track indicators visible from the exterior were diminished. Just prior to opening the door on Side A, there was little visible smoke from the structure (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Experiment 13 at 00:09:56 (Prior to Ventilation)

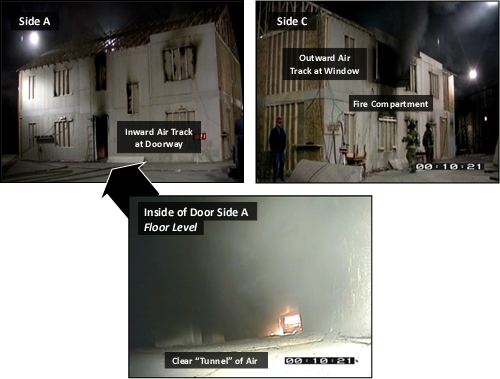

As illustrated in Figure 5, a bi-directional air track was created when the front door was opened. Hot smoke flowed out the upper area of the doorway while air pushed in the bottom creating a tunnel of clear space inside the doorway (but no generalized lifting of the upper layer.

Figure 5. Experiment 13 at 00:10:14 (Door Open)

As illustrated in Figure 6, opening the upper level window in the family room resulted in a unidirectional air track flowing from the front door to the upper level window in the family room. No significant exhaust of smoke can be seen at the front door, while a large volume of smoke is exiting the window. However, while the tunneling effect at floor level was more pronounced (visibility extended from the front door to the family room), there was no generalized lifting of the upper layer throughout the remainder of the building.

Figure 6. Experiment 13 at 00:10:21 (Door and Window Open)

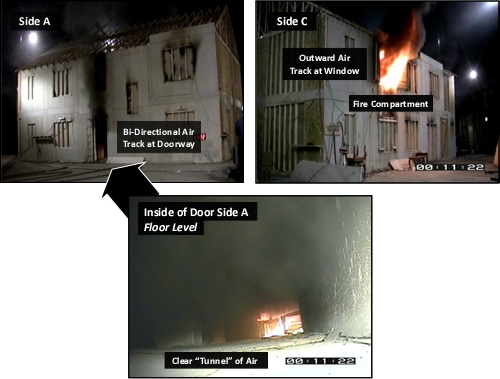

With the increased air flow provided by ventilation through the door on Side A and Window at the upper level on Side C, the fire quickly transitioned to a fully developed stage in the family room. The heat release rate (HRR) and smoke production quickly exceeded the limited ventilation provided by these two openings and the air track at the front door returned to bi-directional (smoke out at the upper level and air in at the lower level) as shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7. Experiment 13 at 00:11:22 (Door and Window Open)

What is the significance of this observation? Movement of smoke out the door (likely the entry point for firefighters entering for fire attack, search, and other interior operations) points to significant potential for flame spread through the upper layer towards this opening. The temperature of the upper layer is hot, but flame temperature is even higher, increasing the radiant heat flux (transfer) to crews working below. Flame spread towards the entry point also has the potential to trap, and injure firefighters working inside.

Gas Velocity and Air Track

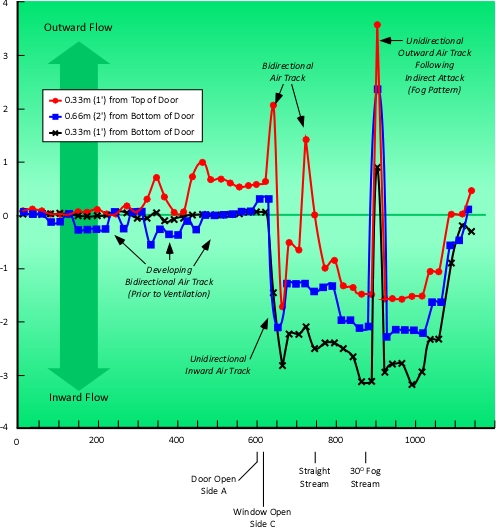

A great deal can be learned by examining both the visual indicators illustrated in Figures 4-7 and measurements taken of gas velocity at the front door. During the ventilation experiments conducted by UL, gas velocities were measured at the front door and at the window used for ventilation (see Figure 3). Five bidirectional probes were placed in the doorway at 0.33 m (1’) intervals. Positive values show gas movement out of the building while negative values show inward gas movement. In order to provide a simplified view of gas movement at the doorway, Figure 8 illustrates gas velocity 0.33 m (1’) below the top of the door, 0.33 m (1’) from the bottom of the door, and 0.66 m (2’) above the bottom of the door.

A bidirectional (out at the top and in at the bottom) air track developed at the doorway before the door was opened (see Figure 8) as a result of leakage at this opening. It is interesting to note variations in the velocity of inward movement of air from the exterior of the building, likely a result of changes in combustion as the fire became ventilation controlled. The outward flow at the upper level resulted in visible smoke on the exterior of the building. While not visible, inward movement of air was also occurring (as shown by measurement of gas velocity at lower levels in the doorway.

Creation of the initial ventilation opening by opening the front door created a strong bidirectional air track with smoke pushing out the top of the door while air rapidly moved in the bottom. Had the door remained the only ventilation opening, this bidirectional flow would have been sustained (as it was in all experiments where the door was the only ventilation opening).

Opening the upper window in the family room resulted in a unidirectional flow inward through the doorway. However, this phenomenon was short lived, with the bidirectional flow reoccurring in less than 60 seconds. This change in air track resulted from increased heat release rate as additional air supply was provided to the fire in the family room.

Figure 8. Front Door Velocities

Note: Adapted from Impact of Ventilation on Fire Behavior in Legacy and Contemporary Residential Construction (p. 243), by Stephen Kerber, Northbrook, IL: Underwriters Laboratories, 2011.

Note: Adapted from Impact of Ventilation on Fire Behavior in Legacy and Contemporary Residential Construction (p. 243), by Stephen Kerber, Northbrook, IL: Underwriters Laboratories, 2011.

While not the central focus of the UL research, these experiments also examined the effects of exterior fire stream application on fire conditions and tenability. Each experiment included a 10 second application with a straight stream and a 10 second application of a 30o fog pattern. Between these two applications, fire growth was allowed to resume for approximately 60 seconds.

The straight stream application resulted in a reduction of temperature in the fire compartment and adjacent compartments (where there was an opening to the family room or hallway) as water applied through the upper window on Side C (ventilation opening) cooled the compartment linings (ceiling and opposite wall) and water deflected off the ceiling dropped onto the burning fuel. As the stream was applied, air track at the door on Side A changed from bidirectional to unidirectional (inward). This is likely due to the reduction of heat release rate achieved by application of water onto the burning fuel with limited steam production.

When the fog pattern was applied, there was also a reduction of temperature in the fire compartment and adjacent compartments (where there was an opening in the family room or hallway) as water was applied through the upper window on Side C (ventilation opening) cooled the upper layer, compartment linings, and water deflected off the ceiling dropped onto the burning fuel. The only interconnected area that showed a brief increase in temperature was the ceiling level in the dining room. However, lower levels in this room showed an appreciable drop in temperature. Air track at the door on Side A changed from bidirectional to unidirectional (outward) when the fog stream was applied. This effect is likely due to air movement inward at the window on Side C and the larger volume of steam produced on contact with compartment linings as a result of the larger surface area of the fog stream.

The effect of exterior streams will be examined in more detail in a subsequent post.

Important Lessons

The fifth tactical implication identified in the Underwriters Laboratories study of the Impact of Ventilation on Fire Behavior in Legacy and Contemporary Residential Construction (Kerber, 2011) is described as failure of the smoke layer to lift following horizontal natural ventilation and smoke tunneling and rapid air movement in through the front door.

Additional lessons that can be learned from this experiment include:

- Ventilating horizontally at a high point results in higher flow of both air and smoke.

- Increased inward air flow results in a rapid increase in heat release rate.

- The rate of fire growth quickly outpaced the capability of the desired exhaust opening, returning the intended inlet to a bi-directional air track (potentially placing firefighters entering for fire attack or search at risk due to rapid fire spread towards their entry point).

Tactical applications of this information include:

- Ensure that the attack team is in place with a charged line and ready to (or has already) attack the fire (not simply ready to enter the building) before initiating horizontal ventilation.

- Cool the upper layer any time that it is above 100o C (212o F) to reduce radiant and convective heat flux and to limit potential for ignition and flaming combustion in the upper layer.

Note that this research project did not examine the impact of gas cooling, but examination of the temperatures at the upper levels in this experiment (and others in this series) point to the need to cool hot gases overhead.

What’s Next?

I am on the hunt for videos that will allow readers to apply the tactical implications of the UL study that have been examined to this point in conjunction with the B-SAHF fire behavior indicators. My next post will likely provide an expanded series of exercises in Reading the Fire.

The next tactical implication identified in the UL study (Kerber, 2011) examines the hazards encountered during Vent Enter Search (VES) tactical operations. A subsequent post will examine this tactic in some detail and explore this tactical implication in greater depth.

References

Kerber, S. (2011). Impact of ventilation on fire behavior in legacy and contemporary residential construction. Retrieved July 16, 2011 from http://www.ul.com/global/documents/offerings/industries/buildingmaterials/fireservice/ventilation/DHS%202008%20Grant%20Report%20Final.pdf

Tags: B-SAHF, burning regime, FBI, fire behavior, fire behavior indicators, fire development, fire research, practical fire dynamics, reading the fire, Tactical Ventilation, vent controlled fire, ventilation