Fire Behavior Case Study

Townhouse Fire: Washington, DC

Monday, September 7th, 2009

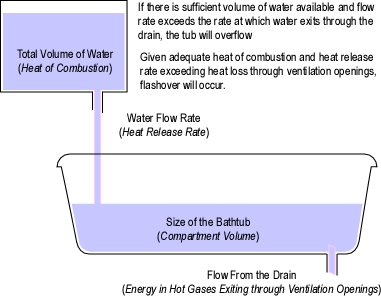

This series of posts focused on Understanding Flashover has provided a definition of flashover; examined flashover in the context of fire development in both fuel and ventilation controlled fires; and looked at the importance of air track on rapid fire progression through multiple compartments. To review prior posts see:

- Myths and Misconceptions

- Myths and Misconceptions: Part 2

- The Ventilation Paradox

- The Importance of Air Track

This post begins study of an incident that resulted in two line-of-duty deaths as a result of extreme fire behavior in a townhouse style apartment building in Washington, DC. This case study provides an excellent learning opportunity as it was one of the first times that the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) Fire Dynamics Simulator (FDS) and Smokeview were used in forensic fire scene reconstruction to investigate fire dynamics involved in a line-of-duty death. Data development of this case study was obtained from Death in the line of duty, Report 99-21 (NIOSH, 1999), Report from the reconstruction committee: Fire at 3146 Cherry Road NE, Washington DC, May 30, 1999 (District of Columbia (DC Fire & EMS, 2000), and Simulation of the Dynamics of the Fire at 3146 Cherry Road NE Washington D.C., May 30, 1999 (Madrzykowski & Vettori, 2000).

The Case

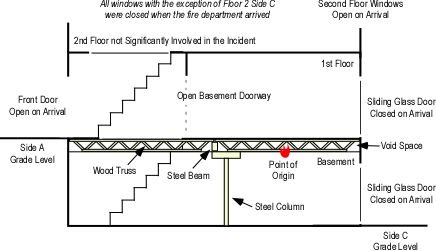

In 1999, two firefighters in Washington, DC died and two others were severely injured as a result of being trapped and injured by rapid fire progress. The fire occurred in the basement of a two-story, middle of building, townhouse apartment with a daylight basement (two stories on Side A, three stories on Side C).

Figure 1. Cross Section of 3146 Cherry Road NE

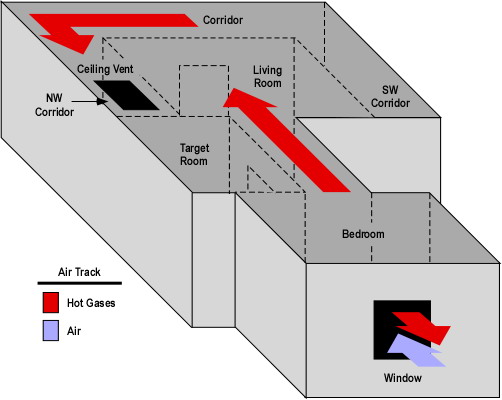

The first arriving crews entered Floor 1 from Side A to search for the location of the fire. Another crew approached from the rear and made entry to the basement through a patio door on Side C. Due to some confusion about the configuration of the building and Command’s belief that the crews were operating on the same level, the crew at the rear was directed not to attack the fire. During fireground operations, the fire in the basement intensified and rapidly extended to the first floor via the open, interior stairway.

Building Information

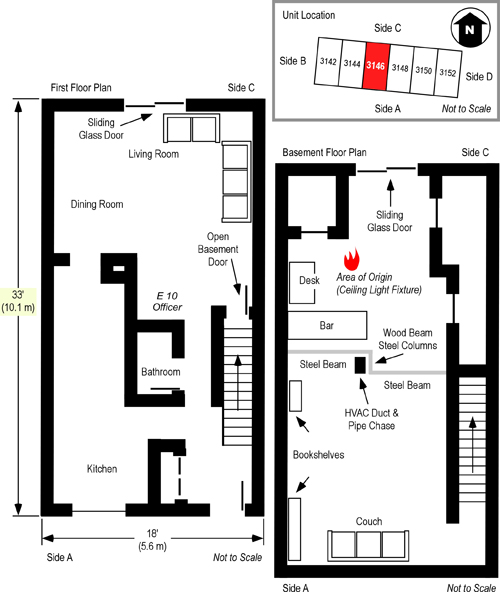

The unit involved in this incident was a middle of row 18′ x 33′ (5.6 m x 10.1 m) two-story townhouse with a daylight basement (see Figures 1 and 3). The building was of wood frame construction with brick veneer exterior and non-combustible masonry firewalls separating six individual dwelling units. Floors were supported by lightweight, parallel chord wood trusses. This type of engineered floor support system provides substantial strength, but has been demonstrated to fail quickly under fire conditions (NIOSH, 2005). In addition, the design of this type of engineered system results in a substantial interstitial void space between the ceiling and floor as illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Parallel Chord Truss Construction

Note: This is not an illustration of the floor assembly in the Cherry Road Townhouse. It is provided to illustrate the characteristics of wood, parallel chord truss construction.

The trusses ran from the walls on Sides A and C and were supported by steel beams and columns at the center of the unit (See Figure 3). The basement ceiling consisted of wood fiber ceiling tiles on wood furring strips which were attached to the bottom chord of the floor trusses. Basement walls were covered with gypsum board (sheetrock) and the floor was carpeted. A double glazed sliding glass door protected by metal security bars was located on Side C of the basement, providing access from the exterior. Side C of the structure (see Figure 3) was enclosed by a six-foot wood and masonry fence. The finished basement was used as a family room and was furnished with a mix of upholstered and wood furniture.

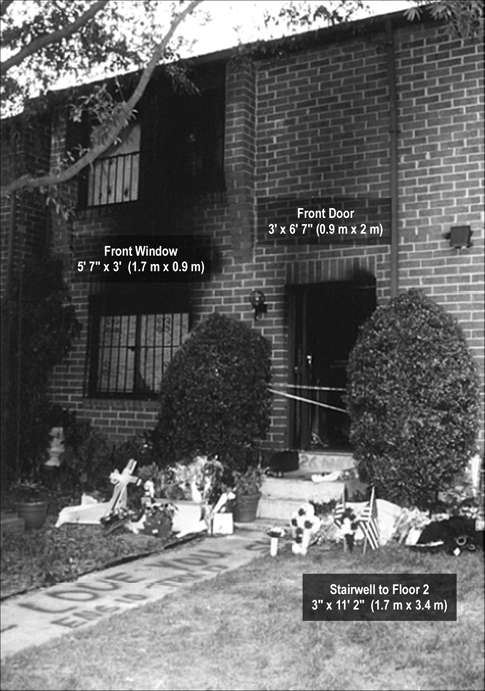

The first floor of the townhouse was divided into the living room, dining room, and kitchen. The basement was accessed from the interior via a stairway leading from the living room to the basement. The door to this stairway was open at the time of the fire (see Figures 1 and 3). The walls and ceilings on the first floor were covered with gypsum board (sheetrock) and the floor was carpeted. Contents of the first floor were typical of a residential living room and kitchen. A double glazed sliding glass door protected by metal security bars similar to that in the basement was located on Side C of the first floor. An entry door and double glazed kitchen window were located on Side A (see Figure 3). A stairway led to the second floor from the front entry. The second floor contained bedrooms (but was not substantively involved in this incident). There were double glazed windows on Sides A and C of Floor 2.

Figure 3. Plot and Floor Plan-3146 Cherry Road NE

Note: Adapted from Report from the Reconstruction Committee: Fire at 3146 Cherry Road NE, Washington DC, May 30, 1999, p. 18 & 20. District of Columbia Fire & EMS, 2000; Simulation of the Dynamics of the Fire at 3146 Cherry Road NE, Washington D.C., May 30, 1999, p. 12-13, by Daniel Madrzykowski & Robert Vettori, 2000. Gaithersburg, MD: National Institute of Standards and Technology, and NIOSH Death in the Line of Duty Report 99 F-21, 1999, p. 19.

Figure 4. Side A 3146 Cherry Road NE

Note: Adapted from Report from the Reconstruction Committee: Fire at 3146 Cherry Road NE, Washington DC, May 30, 1999, p. 17. District of Columbia Fire & EMS, 2000 and Simulation of the Dynamics of the Fire at 3146 Cherry Road NE, Washington D.C., May 30, 1999, p. 5, by Daniel Madrzykowski & Robert Vettori, 2000. Gaithersburg, MD: National Institute of Standards and Technology.

Figure5. Side C 3146 Cherry Road NE

Note: Adapted from Report from the Reconstruction Committee: Fire at 3146 Cherry Road NE, Washington DC, May 30, 1999, p. 19. District of Columbia Fire & EMS, 2000 and Simulation of the Dynamics of the Fire at 3146 Cherry Road NE, Washington D.C., May 30, 1999, p. 5, by Daniel Madrzykowski & Robert Vettori, 2000. Gaithersburg, MD: National Institute of Standards and Technology.

The Fire

The fire originated in an electrical junction box attached to a fluorescent light fixture in the basement ceiling (see Figures 1 and 3). The occupants of the unit were awakened by a smoke detector. The female occupant noticed smoke coming from the floor vents on Floor 2. She proceeded downstairs and opened the front door and then proceeded down the first floor hallway towards Side C, but encountered thick smoke and high temperature. The female and male occupants exited the structure, leaving the front door open, and made contact with the occupant of an adjacent unit who notified the DC Fire & EMS Department at 0017 hours.

Questions

It is important to remember that consideration of how a fire may develop and the relationship between fire behavior and your strategies and tactical operations must begin prior to the time of alarm. Assessment of building factors and fire behavior prediction should be integrated with pre-planning.

- Based on the information provided about the fire and building conditions, how would you anticipate that this fire would develop?

- What concerns would you have if you were the first arriving company at this incident?

More to Follow

My next post will examine dispatch information and initial tactical operations by first alarm companies.

Ed Hartin, MS, EFO, MIFireE, CFO

References

District of Columbia (DC) Fire & EMS. (2000). Report from the reconstruction committee: Fire at 3146 Cherry Road NE, Washington DC, May 30, 1999. Washington, DC: Author.

Madrzykowski, D. & Vettori, R. (2000). Simulation of the Dynamics of the Fire at 3146 Cherry Road NE Washington D.C., May 30, 1999, NISTR 6510. August 31, 2009 from http://fire.nist.gov/CDPUBS/NISTIR_6510/6510c.pdf

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). (1999). Death in the line of duty, Report 99-21. Retrieved August 31, 2009 from http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/fire/reports/face9921.html

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). (2005). NIOSH Alert: Preventing Injuries and Deaths of Fire Fighters Due to Truss System Failures. Retrieved August 31, 2009 from http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/fire/reports/face9921.html