Fully Developed Fires:

Key Fire Behavior Indicators

Thursday, October 22nd, 2009

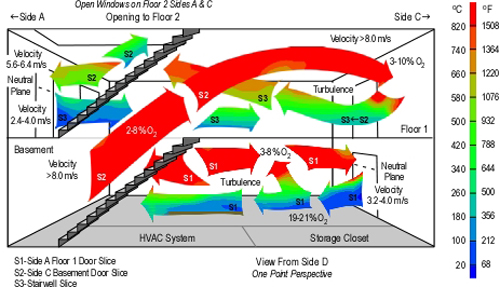

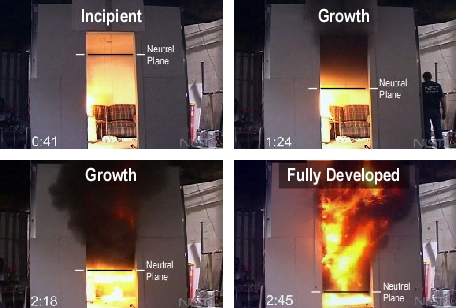

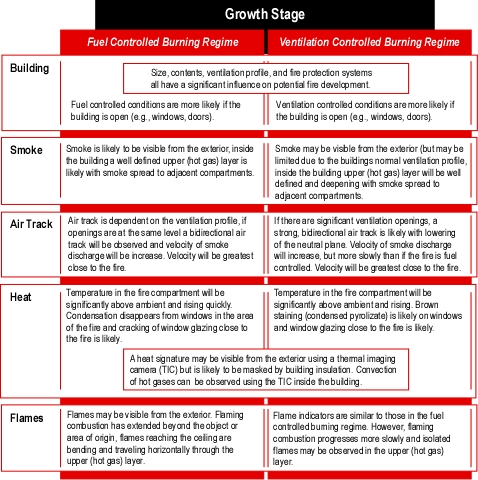

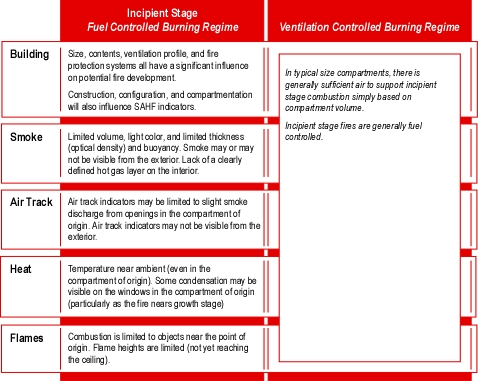

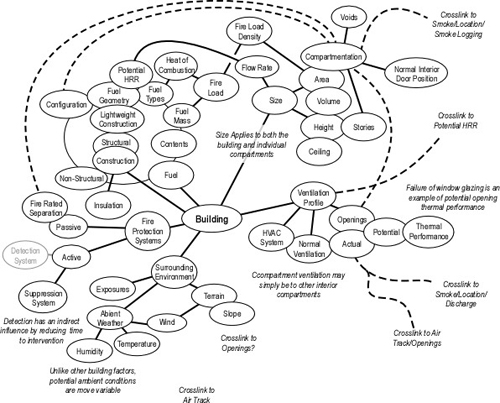

This post continues examination of key indicators used to recognize stages of fire development (i.e., incipient, growth, fully developed, and decay), burning regimes (i.e., fuel and ventilation controlled) with a look at indicators of the fully developed stage of fire development. Most buildings are comprised of multiple, interconnected compartments and fire conditions can vary widely from compartment to compartment. Fire in the compartment of origin may have reached the fully developed stage, while adjacent compartments may have just entered the growth stage.

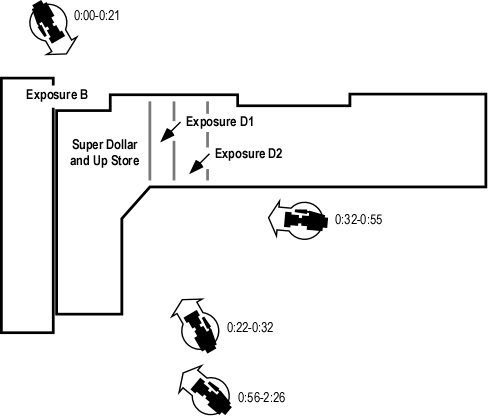

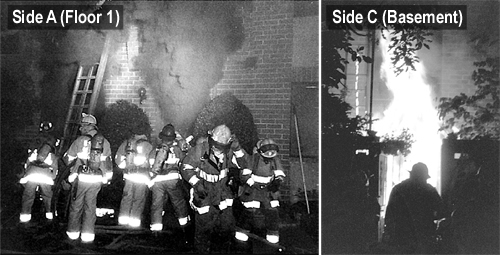

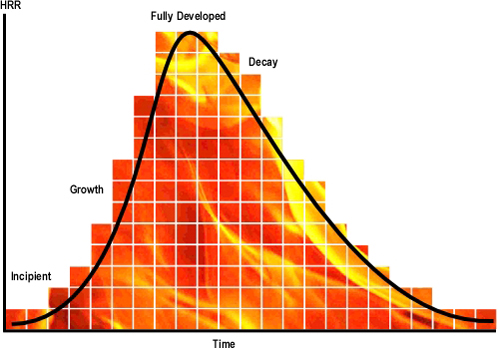

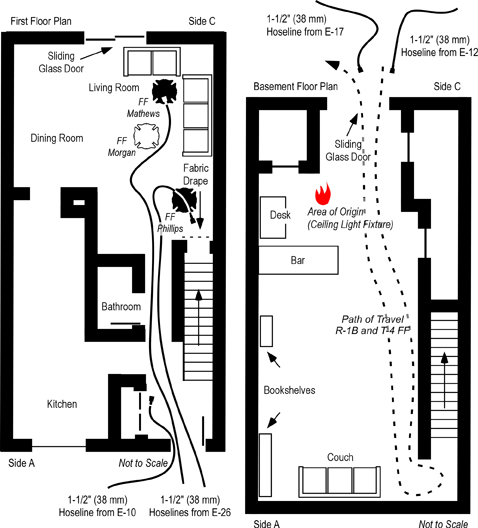

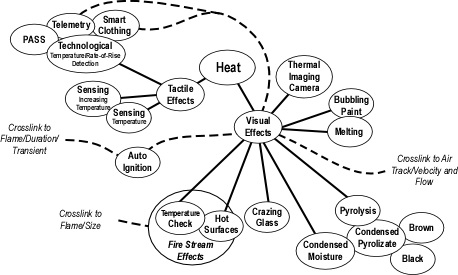

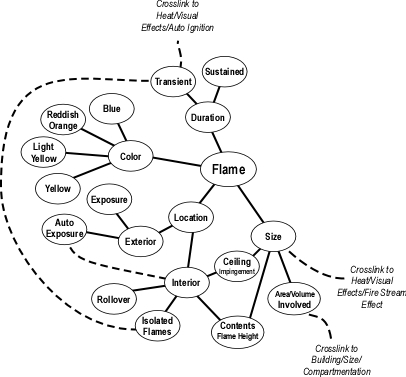

Figure 1. Fully Developed Fire

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) Death in the Line of Duty Report F2007-02 (2009) recommends that fire service agencies: “Train fire fighters to recognize the conditions that forewarn of a flashover/flameover [rollover] and communicate fire conditions to the incident commander as soon as possible” (p. 2). Note: flameover and Rollover are synonyms.

Flameover (Rollover): The condition where unburned fuel (pyrolyzate) from the originating fire has accumulated in the ceiling layer to a sufficient concentration (i.e., at or above the lower flammable limit) that it ignites and burns; can occur without ignition of, or prior to, the ignition of other fuels separate from the origin. (NFPA 921, 2008, 3.3.67 and 3.3.137)

Recognition of key fire behavior indicators is critical. However, communication of this information to the incident commander (as it may impact on strategies) alone is not sufficient. Companies working in the fire environment must proactively mitigate this threat through effective fire control and ventilation strategies and tactics.

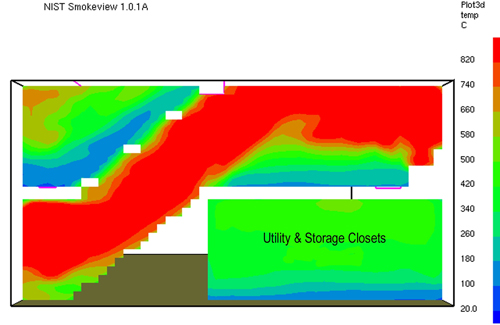

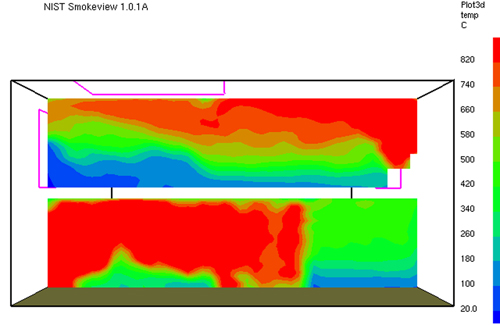

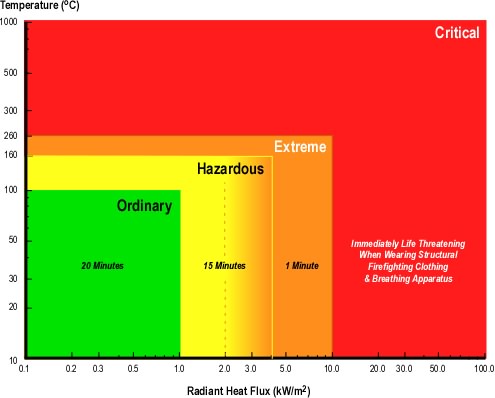

Flashover

Flashover is the sudden transition from a growth stage to fully developed fire. When flashover occurs, there is a rapid transition to a state of total surface involvement of all combustible material within the compartment. Conditions for flashover are defined in a variety of different ways. In general, ceiling temperature in the compartment must reach 500o-600o C (932o-1112o F) or the heat flux (a measure of heat transfer) to the floor of the compartment must reach 15-20 kW/m2 (1.32 Btu/s/ft2)-1.76 Btu/s/ft2). When flashover occurs, burning gases will push out openings in the compartment (such as a door leading to another room) at a substantial velocity (Karlsson & Quintiere, 2000).

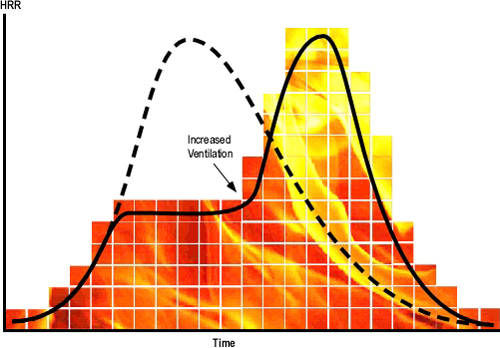

It is important to remember that flashover does not always occur. There must be sufficient fuel and oxygen for the fire to reach flashover. If the initial object that is ignited does not contain sufficient energy (heat of combustion) and does not release it quickly enough (heat release rate), flashover will not occur (e.g., small trash can burning in the middle of a large room). Likewise, if the fire sufficiently depletes the available oxygen, heat release rate will drop and the fire in the compartment will not reach flashover (e.g., small room with sealed windows and the door closed). A fire that fails to reach a sufficient heat release rate for flashover to occur due to limited ventilation presents a significant hazard as increased ventilation may result in a ventilation induced flashover (see Understanding Flashover: Myths & Misconceptions Part 2 and The Ventilation Paradox).

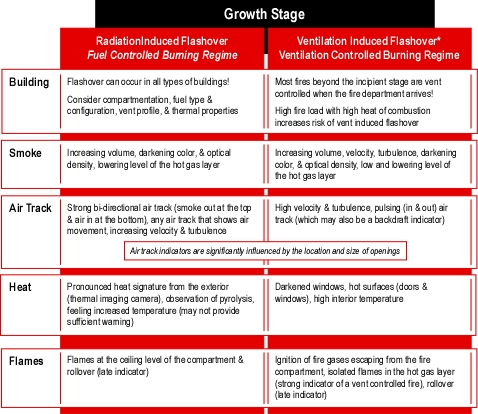

Indicators of Flashover Potential

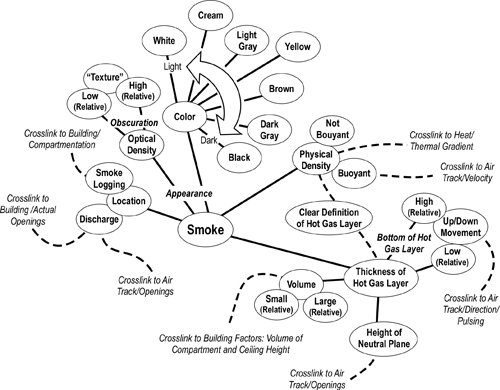

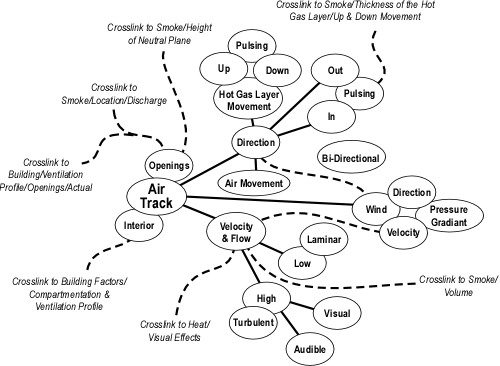

Recognizing flashover and understanding the mechanisms that cause this extreme fire behavior phenomenon is important. However, the ability to recognize key indicators and predict the probability of flashover is even more important. Indicators of potential or impending flashover are listed in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Indicators of Potential Flashover

If the fire in our residential scenario is nearing flashover (in the compartment of origin) what fire behavior indicators might be observed? Use the B-SAHF model to help you frame your answers.

You have responded to a fire in a one-story single family dwelling of wood frame construction. A fire which started in a bedroom on the Alpha Bravo corner of the structure is nearing flashover. A thick hot gas layer has developed in the bedroom and is flowing out the open door into the hallway. The fire has extended to the bed and flames in the plume have reached the ceiling and have begun to extend horizontally in the ceiling jet. Fuel packages below the level of the hot gas layer (e.g., furniture, carpet, and contents) are beginning to pyrolize.

- What conditions would you expect to see from the exterior of the structure?

- What indicators may be visible from the front door as you make entry?

Remember that fire conditions will vary throughout the building. While the fire is in the growth stage and nearing flashover in the bedroom, conditions may be different in other compartments within the building.

- What indicators would you anticipate observing as you traveled through the living room to the hallway leading to the bedroom?

- What conditions would you find in the hallway outside the fire compartment?

- After making entry, consider if conditions are different than you anticipated?

- Why might this be the case?

- What differences in conditions would be cause for concern?

- How might your answers to the preceding questions have differed if the bedroom door was closed and fire growth limited by ventilation?

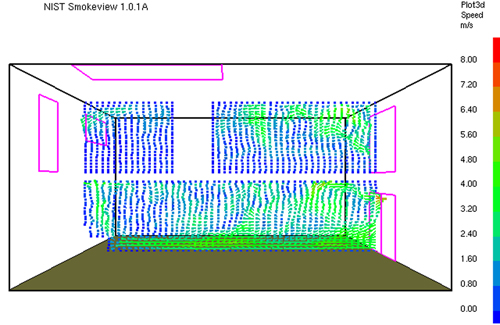

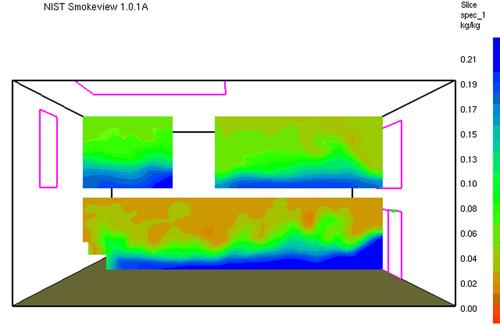

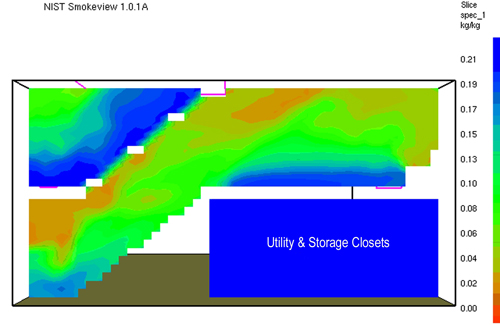

Fully Developed Fire

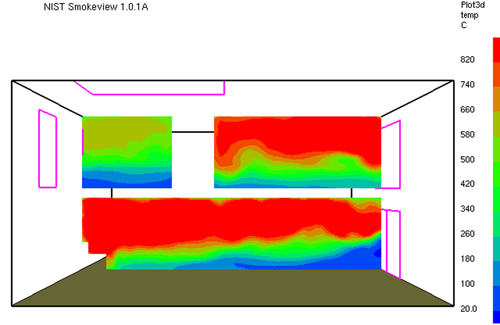

At this post-flashover stage, energy release is at its greatest, but is generally limited by ventilation (more on this in a bit). Unburned gases accumulate at the ceiling level and frequently burn as they leave the compartment, resulting in flames showing from doors or windows. The average gas temperature within a compartment during a fully developed fire ranges from 700o-1200o C (1292o-2192o F)

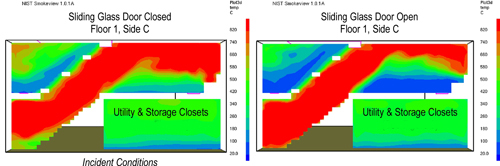

Remember that the compartment where the fire started may reach the fully developed stage while other compartments have not yet become involved. Hot gases and flames extending from the involved compartment transfer heat to other fuel packages (e.g., contents, compartment linings, and structural materials) resulting in fire spread. Conditions can vary widely with a fully developed fire in one compartment, a growth stage fire in another, and an incipient fire in yet another. It is important to note that while a fire in an adjacent compartment may be incipient, conditions within the structure are immediately dangerous to life and health (IDLH).

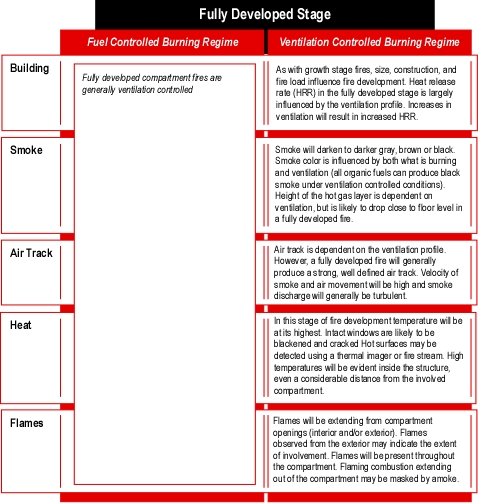

Indicators of a Fully Developed Fire

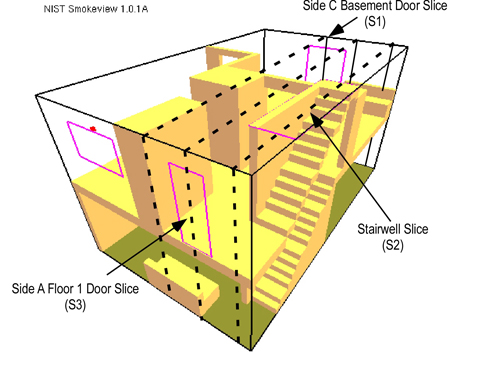

Remember that a fully developed fire refers to conditions within a given compartment or compartments. It does not necessarily mean that the entire building is fully involved. Figure 3 lists indicators of fully developed fire conditions.

Figure 3. FBI-Fully Developed Stage

If the fire in our residential scenario has progressed to the fully developed stage (in the compartment of origin) what fire behavior indicators might be observed? Use the B-SAHF model to help you frame your answers.

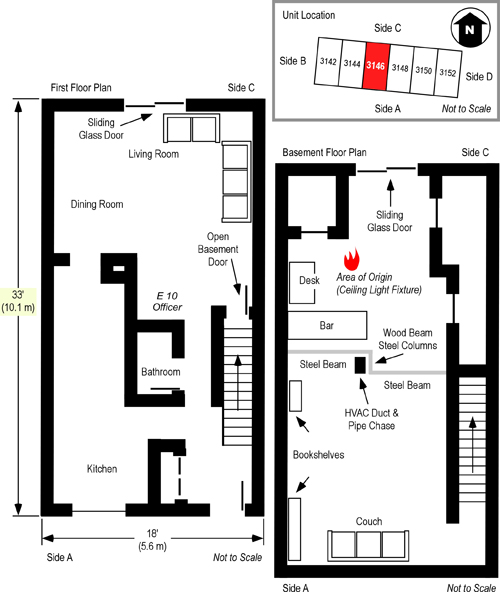

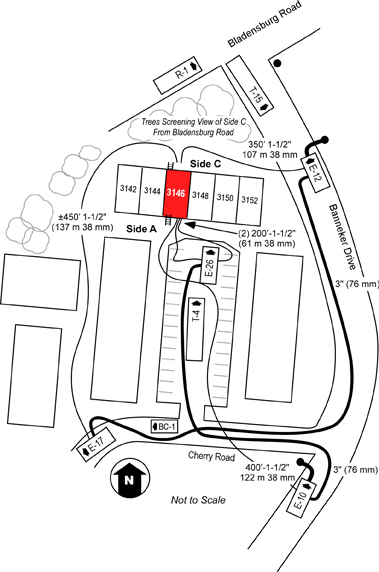

You have responded to a fire in a one-story single family dwelling of wood frame construction. A fire which started in a bedroom on the Alpha Bravo corner of the structure has reached the fully developed stage and now involves the contents of the room and interior finish of this compartment.

- What conditions would you expect to see from the exterior of the structure?

- What indicators may be visible from the front door as you make entry?

Remember that fire conditions will vary throughout the building. While the fire is fully developed in the bedroom, conditions may be different in other compartments within the building.

- What indicators would you anticipate observing as you traveled through the living room to the hallway leading to the bedroom?

- What conditions would you find in the hallway outside the fire compartment?

- After making entry, consider if conditions are different than you anticipated?

- Why might this be the case?

- What differences in conditions would be cause for concern?

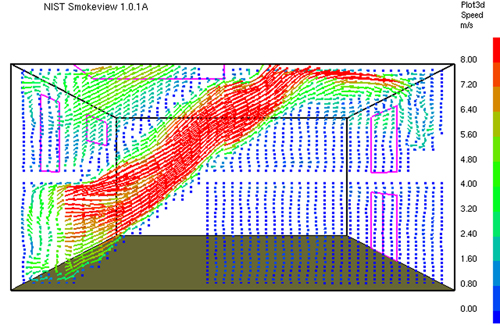

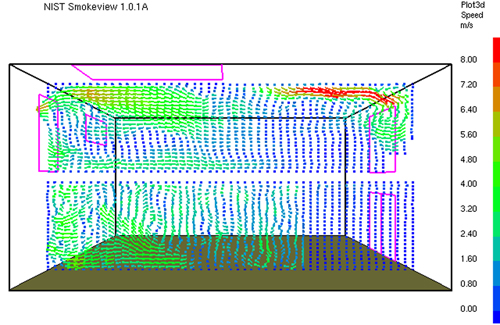

Ventilation Controlled Fires

When the fire is burning in a ventilation controlled state, any increase in the supply of oxygen to the fire will result in an increase in heat release rate. Increase in ventilation may result from firefighters making entry into the building (the access point is a ventilation opening), tactical ventilation (performed by firefighters), or unplanned ventilation (e.g., failure of window glazing due to elevated temperature).

It is essential to recognize when the fire is, or may be ventilation controlled, and the influence of planned and unplanned changes in ventilation profile on fire behavior. Most compartment fires in the late growth stage or which are fully developed are ventilation controlled when the fire department arrives. Even if the fire has not entered the decay stage due to limited ventilation, the increased oxygen provided by increases in ventilation (such as that caused by opening the door to make entry) will increase heat release rate. This is not to say that increased ventilation is a bad thing, but firefighters should be prepared to deal with this change in fire behavior.

Remember the Past

Line of duty deaths involving extreme fire behavior has a significant impact on the family of the firefighter or firefighters involved as well as their department. Department investigative reports and NIOSH Death in the Line of Duty reports point out lessons learned from these tragic events. However, as time passes, these events fade from the memory of those not intimately connected with the individuals involved. It is important that we remember the lessons of the past as we continue our study of fire behavior and work to improve firefighter safety and effectiveness on the fireground.

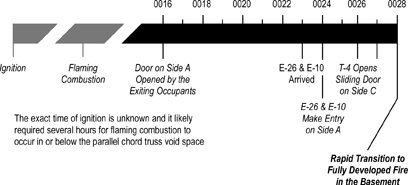

October 29, 2008

Firefighter Adam Cody Renfroe

Crossville Fire Department, Alabama

The Crossville Fire Department was dispatched to a fire in a single-family residence. was on the first engine to arrive on the scene to find thick, black smoke from the roof and a report that all occupants were out of the house.

Firefighter Renfroe and another firefighter advanced a hoseline to the front door of the residence. He sent the other firefighter back to the fire truck for a tool. When the firefighter returned, Firefighter Renfroe was gone and the nozzle remained by the doorway. At about the same time, the fire inside of the structure intensified. Firefighter Renfroe transmitted a distress message from the interior. Firefighters were not immediately able to enter the structure due to fire conditions.

Firefighters discovered Firefighter Renfroe about 4 feet from the home’s back door, but By the time firefighters reached him, he was deceased. The cause of death was smoke inhalation and thermal burns.

For more information on this incident, see NIOSH Death in the Line of Duty Report F2008-34.

Ed Hartin, MS, EFO, MIFireE, CFO

References

Karlson, B. & Quintiere, J. (2000) Enclosure fire dynamics. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). (2009). Death in the Line of Duty Report F2007-02. Retrieved October 22, 2009 from http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/fire/pdfs/face200702.pdf .