Fire Behavior Indicators – A Quick Review

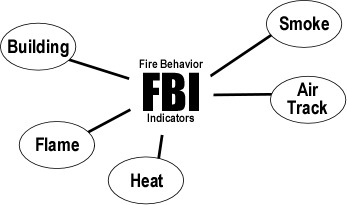

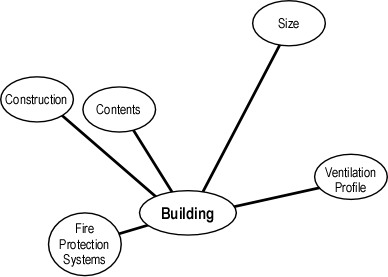

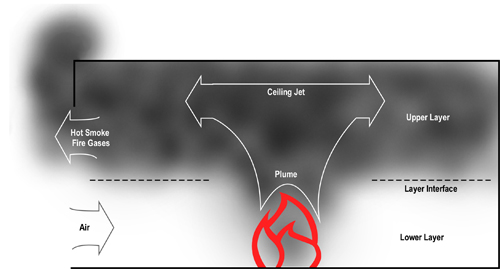

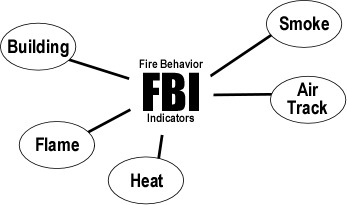

The B-SAHF (Building, Smoke, Air Track, Heat, & Flame) organizing scheme for fire behavior indicators provides a sound method for assessment of current and potential fire behavior in compartment fires. The following provides a quick review of each of these indicator types.

Figure 1. B-SAHF

Building: Many aspects of the building (and its contents) are of interest to firefighters. Building construction influences both fire development and potential for collapse. The occupancy and related contents are likely to have a major impact on fire dynamics as well.

Smoke: What does the smoke look like and where is it coming from? This indicator can be extremely useful in determining the location and extent of the fire. Smoke indicators may be visible on the exterior as well as inside the building. Don’t forget that size-up and dynamic risk assessment must continue after you have made entry!

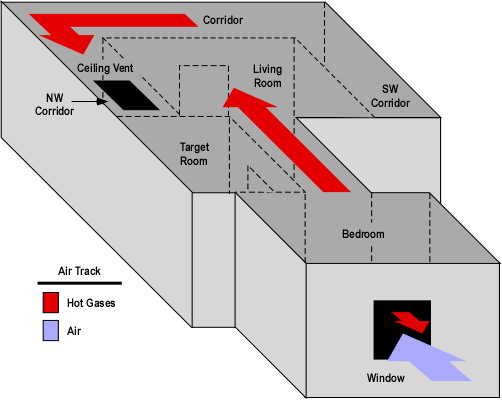

Air Track: Related to smoke, air track is the movement of both smoke (generally out from the fire area) and air (generally in towards the fire area). Observation of air track starts from the exterior but becomes more critical when making entry. What does the air track look like at the door? Air track continues to be significant when you are working on the interior.

Heat: This includes a number of indirect indicators. Heat cannot be observed directly, but you can feel changes in temperature and may observe the effects of heat on the building and its contents. Remember that you are insulated from the fire environment, pay attention to temperature changes, but recognize the time lag between increased temperature and when you notice the difference. Visual clues such as crazing of glass and visible pyrolysis from fuel that has not yet ignited are also useful heat related indicators.

Flame: While one of the most obvious indicators, flame is listed last to reinforce that the other fire behavior indicators can often tell you more about conditions than being drawn to the flames like a moth. However, that said, location and appearance of visible flames can provide useful information which needs to be integrated with the other fire behavior indicators to get a good picture of conditions.

It is important not to focus in on a single indicator, but to look at all of the indicators together. Some will be more important than others under given circumstances.

Getting Started

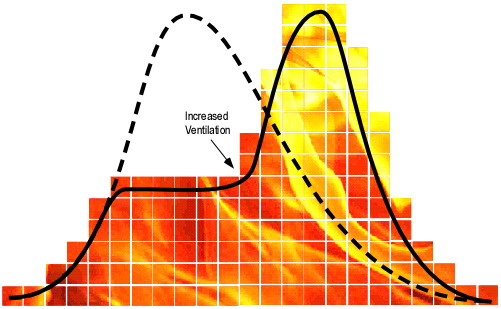

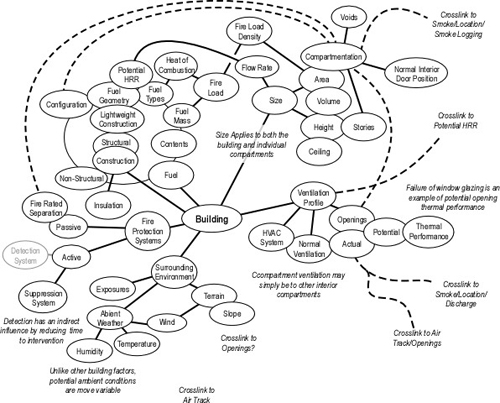

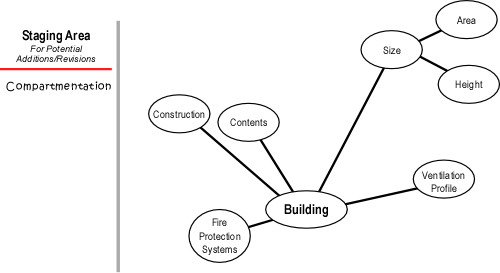

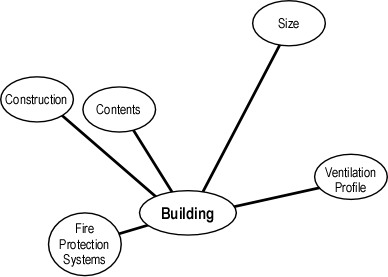

Considering the wide range of different building types and occupancies, developing a concept map of the factors and interrelationships that influence fire behavior is no simple task. As you begin this process, keep in mind that it is important to move from general concepts to more specific details. For example, you might select construction type, contents, size, ventilation profile, and fire protection systems as the fundamental factors as illustrated in Figure 2. (However, you also might choose to approach this differently!).

Figure 2. Basic Building Factors

Remember that this is simply a draft (as will each successive version of your map)! Don’t get hung up on getting it “right”. The key is to get started and give some thought to what might be important. After adding some detail, you may come back and reorganize the map, identifying another basic element. For example, early versions of this map listed Fire Suppression Systems (e.g., automatic sprinklers) as one of the core concepts. However, after adding some detail, this concept was broadened to Fire Protection Systems (e.g., automatic sprinklers, fire detection, and other types of inbuilt fire protection).

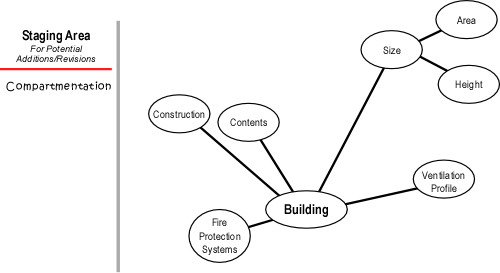

Developing the Detail

Expanding the map requires identification of additional detail for each of the fundamental concepts. If an idea appears to be obviously related to one of the concepts already on the map, go ahead and add it. If you are unsure of where it might go, but it seems important, list it off to the side in a staging area for possible additions. For example, area and height are important concepts related to size. However, compartmentation may be related to size or it may be a construction factor. If you are unsure of where this should appear on the map, place it in the Staging Area for now.

Figure 3. Expanding the Map

Next Steps

Remember that the process of contracting your own map is likely as important as the (never quite) finished product. The following steps may help you expand and refine the building factors segment of the map:

- Look at each of the subcategories individually and brainstorm additional detail. This works best if you collaborate with others.

- Take your partially completed map and notes and visit several different types of buildings. Visualize how a fire might develop and what building features would influence this process.

- Examine the incident profiled in the Remember the Past segment of this post and give some thought to how building factors may have influenced fire behavior and the outcome of this incident.

In addition, I am still posing questions related to B-SAHF using Twitter. Have a look [http://twitter.com/edhartin] and join in by responding to the questions. While this is not a familiar tool to most firefighters, I think that it has great potential.

Thanks

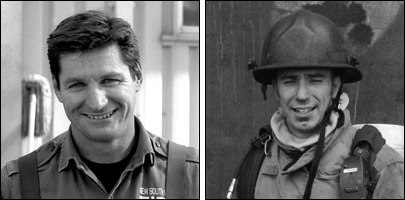

I would also like to thank Senior Instructor Jason Collits of the New South Wales (Australia) Fire Brigades and Lieutenant Matt Leech of Tualatin Valley Fire and Rescue (also an Instructor Trainer with CFBT-US, LLC) for their collaborative efforts on extending and refining our collective understanding of the B-SAHF indicators. Jason and Matt have been using Bubbl.us to develop and share their respective maps and I will be integrating their work into future posts on Fire Behavior Indicators.

Figure 4 Jason Collits and Matt Leech

Remember the Past

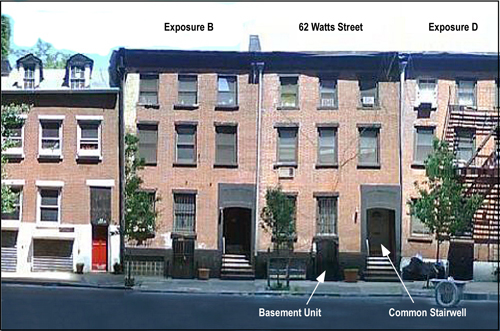

Yesterday was the eighth anniversary of a tragic fire in New York City that claimed the lives of three members of FDNY as a result of a backdraft in the basement of a hardware store.

June 17, 2001

Firefighter First Grade John J. Downing, Ladder 163

Firefighter First Grade Brian D. Fahey, Rescue 4

Firefighter First Grade Harry S. Ford, Rescue 3

Fire Department City of New York

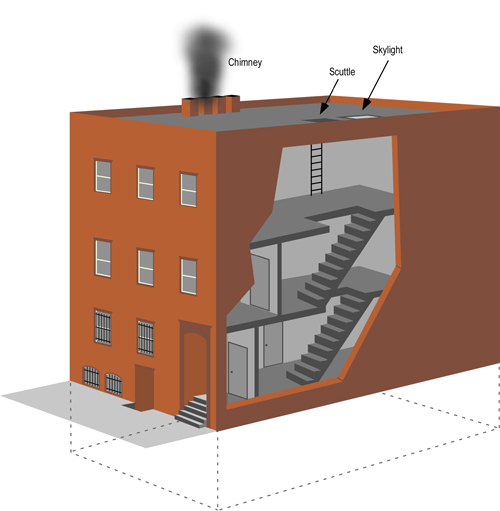

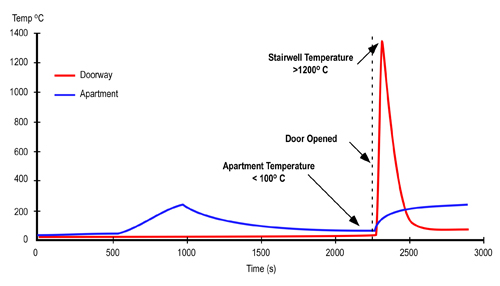

Fire companies were dispatched to a report of a fire in a hardware store. The first- arriving engine company, which had been flagged down by civilians in the area prior to the dispatch, reported a working fire with smoke venting from a second-story window.

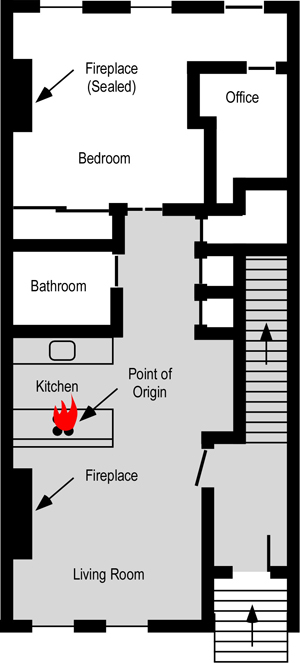

A bystander brought the company officer from the first-arriving engine company to the rear of the building where smoke was observed venting from around a steel basement door. The first-arriving command officer was also shown the door and ordered an engine company to stretch a line to the rear of the building. A ladder company was ordered to the rear to assist in opening the door; Firefighter Downing was a member of this company. The first-due rescue company, including Firefighters Fahey and Ford, searched the first floor of the hardware store and assisted with forcible entry on the exterior.

The incident commander directed firefighters at the rear of the building to open the rear door and attack the basement fire. Firefighters on the first floor were directed to keep the interior basement stairwell door closed and prevent the fire from extending. The rear basement door was reinforced, and a hydraulic rescue tool was employed to open it. Once the first door was opened, a steel gate was found inside, further delaying fire attack.

Firefighters Downing and Ford were attempting to open basement windows on the side of the building, and Firefighter Fahey was inside of the structure on the first floor.

An explosion occurred and caused major structural damage to the hardware store. Three fire-fighters were trapped under debris from a wall that collapsed on the side of the hardware store; several firefighters were trapped on the second floor; firefighters who were on the roof prior to the explosion were blown upwards with several firefighters riding debris to the street below; and fire-fighters on the street were knocked over by the force of the explosion.

The explosion trapped and killed Firefighters Downing and Ford under the collapsed wall; their deaths were immediate. Firefighter Fahey was blown into the basement of the structure. He called for help on his radio, but firefighters were unable to reach him in time.

The cause of death for Firefighters Downing and Ford was internal trauma, and the cause of death for Firefighter Fahey was listed as asphyxiation. Firefighter Fahey’s carboxyhemoglobin level was found to be 63%.

In addition to the three fatalities, 99 firefighters were injured at this incident. The fire was caused when children – two boys, ages 13 and 15 – knocked over a gasoline can at the rear of the hard-ware store. The gasoline flowed under the rear doorway and was eventually ignited by the pilot flame on a hot water heater.

For additional information on this incident, see the following:

NIOSH Death in the Line of Duty Report F2001-23,

Simulation of the Dynamics of a Fire in the Basement of a Hardware Store

Incident Photos by Steve Spak

Ed Hartin, MS, EFO, MIFireE, CFO

References

Grimwood, P., Hartin, E., McDonough, J., & Raffel, S. (2005). 3D firefighting: Training, techniques, & tactics. Stillwater, OK: Fire Protection Publications.

Hartin, E. (2007) Fire behavior indicators: Building expertise. Retrieved June 17, 2009 from www.firehouse.com.

Hartin, E. (2007) Reading the fire: Building factors. Retrieved June 17, 2009 from www.firehouse.com.

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). (2003) Death in the line of duty report F2001-23. Retrieved June 18, 2009 from http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/fire/pdfs/face200123.pdf

Bryner, N. & Kerber, S (2004) Simulation of the dynamics of a fire in the basement of a hardware store – New York, June 17, 2001 NISTR 7137. Retrieved June 18, 2009 from http://www.fire.nist.gov/bfrlpubs/fire06/PDF/f06006.pdf

United States Fire Administration (USFA) Firefighter fatalities in 2001. Retrieved June 18, 2009 from http://www.usfa.dhs.gov/downloads/pdf/publications/fa-237.pdf