Wind Driven Fires

Monday, March 2nd, 2009Weather, Topography, and Fuel

In S-190 Introduction to Wildland Fire Behavior, firefighters learn that weather, topography, and fuel and the principal factors influencing fire behavior in the wildland environment. How might this important concept apply when dealing with fires in the built environment? Factors influencing compartment fire behavior have a strong parallel to those in the wildland environment. Principal influences on compartment fire behavior include fuel, configuration (of the compartment and building), and ventilation.

Wind Driven Compartment Fires

As buildings are designed to minimize the influence of weather on their contents and occupants, weather is not generally considered a major factor in compartment fires. However, this is not always the case. As wildland firefighters recognize, wind can be a major influence on fire behavior and strong winds present a significant threat of extreme fire behavior.

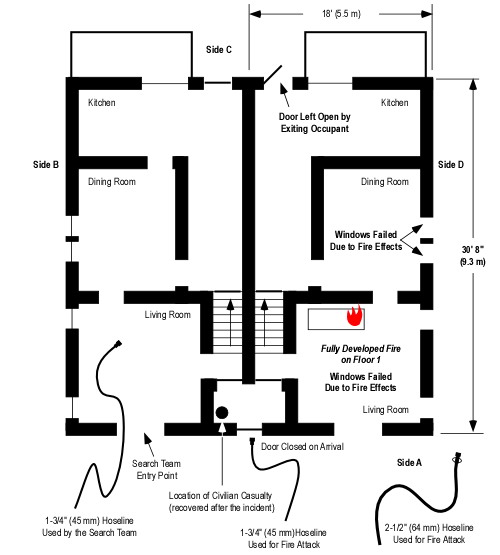

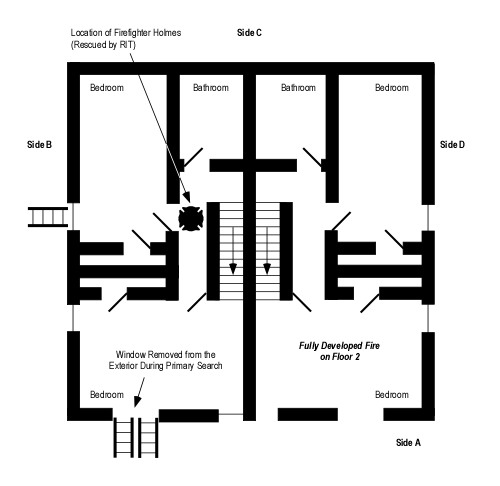

Under fire conditions, unplanned ventilation involves all changes influencing exhaust of smoke, air intake, and movement of smoke within the building that are not part of the incident action plan. These changes may result from the actions of exiting building occupants, fire effects on the building (e.g., failure of window glass), or a wide range of other factors.

Changes in ventilation can increase fire growth and hot smoke throughout the building. Failure of a window in the fire compartment in the presence of wind conditions can result in a significant and rapid increase in heat release. If this is combined with open doors to corridors, unprotected stairwells, and other compartments, wind driven fire conditions have frequently resulted in firefighter injuries and fatalities (see Additional Reading).

NIST Research on Wind Driven Fires

From November 2007 to January 2008, the National Institute of Standards and Technology conducted a series of experiments examining firefighting tactics dealing with wind driven compartment fires. The primary focus of this research was on the dynamics of fire growth and intensity and the influence of ventilation and fire control strategies under wind driven fire conditions. The results of these experiments are presented in Fire Fighting Tactics Under Wind Driven Conditions, published by The Fire Protection Research Foundation.

Tests conducted at NIST’s Large Fire Test Facility (see Figure 1) included establishment of baseline heat release data for the fuels (bed, chairs, sofa, etc), full scale fire tests under varied conditions (e.g., no wind, wind), and experiments involving control of the inlet opening and varied methods of external water application.

Figure 1. NIST Large Fire Test Facility

Note: Photo adapted from Firefighting Tactics Under Wind Driven Conditions.

The objectives of this study were:

- To understand the impact of wind on a structure fire fueled with residential furnishings in terms of temperature, heat flux, heat release rate, and gas concentrations

- To quantify the impact of several novel firefighting tactics on a wind driven structure fire

- Improve firefighter safety

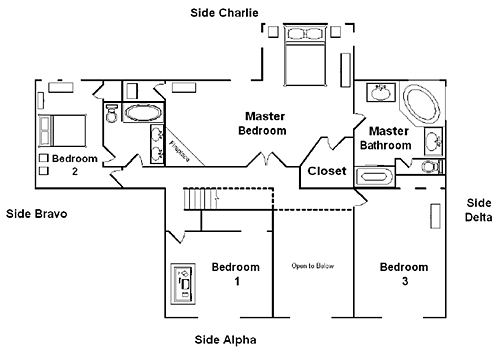

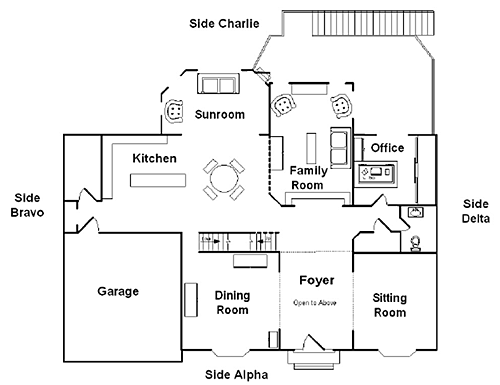

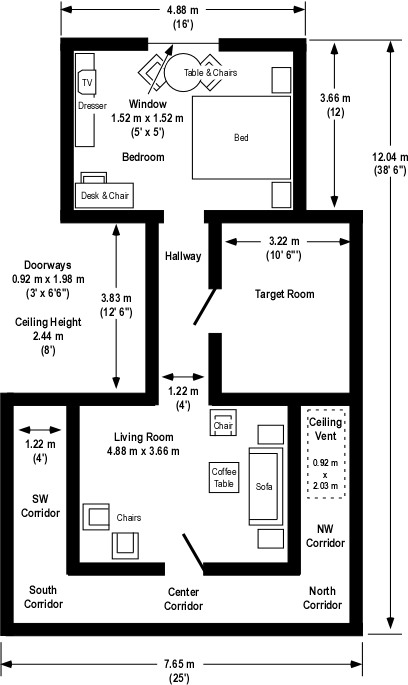

After conducting a series of tests to determine the heat release rate characteristics of the fuels to be used for the full scale tests, NIST conducted eight full scale experiments to examine the impact of wind on fire spread through the multi-room test structure (see Figure 2) and examine the influence of anti-ventilation using wind control devices and the impact of external water application.

Multi-Room Test Structure

All tests were conducted under the 9 m (30′) x 12 m (40′) oxygen consumption calorimetry hood at the NIST Large Fire Test Facility. The test structure was comprised of three compartments; Bedroom, Target Room (used to assess tenability in a compartment adjacent to the ventilation flow), and Living Room, along with an interconnecting hallway and exterior hallways. A large mechanical fan was positioned 7.9 m (26′) away from the window in the bedroom of the test structure (see Figure 2) to provide consistent wind conditions for the experiments.

Figure 2. Configuration of the Multi-Room Test Structure

Note: Adapted from Firefighting Tactics Under Wind Driven Conditions.

The structure was framed with steel studs and wood truss joist I-beams (TJIs) used to support the ceiling. The interior of the compartments were lined with three layers of 13 mm (1/2″) gypsum board. Multiple layers of gypsum board were used to provide the durability required for repetitive experiments (the inner layer was replaced and repairs made to other layers as needed between experiments).

Used furnishings were purchased from a hotel liquidator to obtain 10 sets of similar furniture to use in the heat release rate and full-scale, multi-compartment experiments. Fuel used in the tests included furniture, nylon carpet, and polyurethane carpet padding (the position major furniture items are illustrated in Figures 2 and 3). Fuel load was 348.69 kg (768.73 lbs) in the bedroom, 21.5 kg (47.40 lbs) in the hallway, and 217.6 kg (479.73 lbs) in the living room (no contents were placed in the target room).

Figure 3. Bedroom and Living Room Fuel Load

Note: Photos adapted from Firefighting Tactics Under Wind Driven Conditions.

NIST researchers conducted a series of eight full-scale, multi-compartment fire tests. In each case, a fire was started in the Bedroom using a plastic trash container placed next to the bed (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Placement of the Trash Container

Note: Photos adapted from Firefighting Tactics Under Wind Driven Conditions.

Experiments

The eight tests provided the opportunity to study the dynamics of wind driven compartment fires and several different approaches to limiting the influence of air intake and controlling the fire.

Experiment 1: This test was performed to establish baseline conditions with no wind

Experiment 2: Evaluation of anti-ventilation using a large wind control device placed over the window

Experiment 3: Evaluation of anti-ventilation using a large wind control device placed over the window (second test with a longer pre-burn before deployment of the wind control device).

Experiment 4: Evaluation of anti-ventilation and water application using a small wind control device and 30 gpm (113.6 lpm) spray nozzle from under the wind control device.

Experiment 5: Evaluation of anti-ventilation and water application using a small wind control device and 30 gpm (113.6 lpm) spray nozzle from under the wind control device (second test with a lower wind speed)

Experiment 6: No wind control device, application of water using a hoseline equipped with a combination nozzle at 90 psi (621 kPa) nozzle pressure, providing a flow rate of 80 gpm (303 lpm).

Experiment 7: No wind control device, application of water using a hoseline equipped with a 15/16″ smooth bore nozzle at 50 psi (345 kPa) nozzle pressure, providing a flow rate of 160 gpm (606 lpm) (test was conducted with the living room corridor door closed).

Experiment 8: No wind control device, application of water using a hoseline equipped with a 15/16″ smooth bore nozzle at 50 psi (345 kPa) nozzle pressure, providing a flow rate of 160 gpm (606 lpm) (second test with the living room corridor door open).

Note: The nozzles for these tests (100 gpm at 100 psi combination nozzle and 15/16″ solid stream nozzle were selected as to be representative of those used by the fire service in the United States (personal correspondence, S. Kerber, February 28, 2009). However, it is important to note that in comparing the results, that the combination nozzle was under pressurized (80 psi, rather than 100 psi) resulting in large droplet size. In addition, the 100 gpm flow rate was 50% of that applied through the solid stream nozzle and is likely considerably lower than the flow capability of combination nozzles typically used with 1-3/4″ (45 mm) hose.

Important Findings

The first experiment was conducted without any external wind or tactical intervention. The baseline data generated during this test was critical to evaluating the outcome of subsequent experiments and demonstrated a number of concepts that are critical to firefighter safety:

Smoke is fuel. A ventilation limited (fuel rich) condition had developed prior to the failure of the window. Oxygen depleted combustion products containing carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide and unburned hydrocarbons, filled the rooms of the structure. Once the window failed, the fresh air provided the oxygen needed to sustain the transition through flashover, which caused a significant increase in heat release rate.

Venting does not always equal cooling. In this experiment, post ventilation temperatures and heat fluxes all increased, due to the ventilation induced flashover.

As discussed in early posts, Fuel & Ventilation and Myth of the Self Vented Fire understanding the relationship between oxygen and heat release rate, the hazards presented by ventilation controlled fires, and the influence of ventilation on fire development is critical to safe and effective fireground operations.

Fire induced flows. Velocities within the structure exceeded 5 m/s (11 mph), just due to the fire growth and the flow path that was set-up between the window opening and the corridor vent.

Avoid the flow path. The directional nature of the fire gas flow was demonstrated with thermal conditions, both temperature and heat flux, which were twice as high in the “flow” portion of the corridor as opposed to the “static” portion of the corridor in Experiment 1 [not wind driven]. Thermal conditions in the flow path were not consistent with firefighter survival.

Previous posts have presented case studies based on incidents in Loudoun County Virginia and Grove City, Pennsylvania in which convective flow was a significant factor rapid fire progress that entrapped and injured firefighters, in one case fatally. Previous NIST research investigating a multiple line-of-duty death that occurred in a townhouse fire at 3146 Cherry Road in Washington, DC in 1999 also emphasized the influence of flow path on fire conditions and tenability.

More to Follow

Subsequent posts will examine the NIST wind driven fire tests in greater detail.

Ed Hartin, MS, EFO, MIFireE, CFO

References

Madrzykowski, D. & Kerber, S. (2009). Fire Fighting Tactics Under Wind Driven Conditions. Retrieved (in four parts) February 28, 2009 from http://www.nfpa.org/assets/files//PDF/Research/Wind_Driven_Report_Part1.pdf; http://www.nfpa.org/assets/files//PDF/Research/Wind_Driven_Report_Part2.pdf;http://www.nfpa.org/assets/files//PDF/Research/Wind_Driven_Report_Part3.pdf;http://www.nfpa.org/assets/files//PDF/Research/Wind_Driven_Report_Part4.pdf.

Madrzykowski, D. & Vettori, R. (2000). Simulation of the Dynamics of the Fire at 3146 Cherry Road NE, Washington D.C., May 30, 1999. Retrieved March 1, 2009 from http://fire.nist.gov/CDPUBS/NISTIR_6510/6510c.pdf

Additional Reading

The following investigative reports deal with firefighter line of duty deaths involving wind driven fire events during structural firefighting.

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). (1999). Death in the line of duty, Report F99-01. Retrieved February 28, 2009 from http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/fire/pdfs/face9901.pdf

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). (1999). Death in the line of duty, Report F98-26. Retrieved February 28, 2009 from http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/fire/pdfs/face9826.pdf

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). (2002). Death in the line of duty, Report F2001-33. Retrieved February 28, 2009 from http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/fire/pdfs/face200133.pdf

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). (2007). Death in the line of duty, Report F2005-03. Retrieved February 28, 2009 from http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/fire/pdfs/face200503.pdf

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). (2008). Death in the line of duty, Report F2007-12. Retrieved February 28, 2009 from http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/fire/pdfs/face200712.pdf

Prince William County Department of Fire and Rescue (2007). Line of duty investigative report: Technician I Kyle Wilson. Retrieved February 28, 2009 from http://www.pwcgov.org/default.aspx?topic=040061002930004566

Texas State Fire Marshal’s Office. (2001). Firefighter Fatality Investigation, Investigation Number 02-50-10. Retrieved February 28, 2009 from http://www.tdi.state.tx.us/reports/fire/documents/fmloddjahnke.pdf