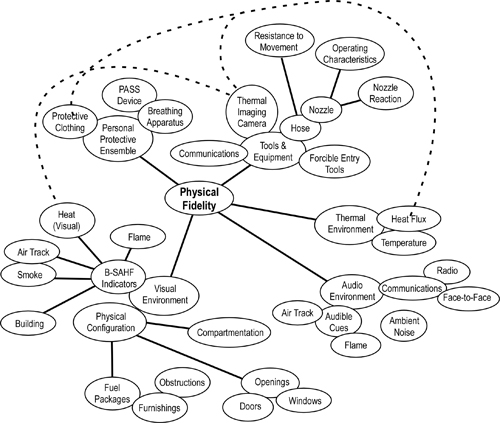

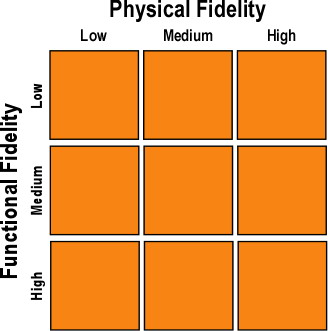

Live Fire Simulations: Key Elements of Fidelity examined some of the important elements in physical fidelity, the extent to which the simulation looks and feels real. This post will begin the process of identifying key aspects of functional fidelity, the extent to which the simulation works and reacts realistically.

Maintaining the Balance

One important factor to consider in live fire training simulation is that despite the fact that it is a training exercise, the fire is real. While I too use the terms training fire and real fire, the combustion processes and fire dynamics in live fire training are the same as encountered in a structure fire. What is different is the type, amount, and geometry of the fuel used and the ventilation profile.

Providing complete functional fidelity (as well as physical fidelity) simply requires that structural environment, fuel loading, and ventilation be the same as would be encountered in an actual incident. However, this substantially increases variability of outcome and the risk to participants.

Use of a purpose built structure allows control of variability and provides the ability for repetitive and ongoing training. Purpose-built structures are often designed to use either solid Class A fuel or gaseous Class B fuel. Facility design and selection of fuel type should be based on a wide range of factors including provision of adequate fidelity for the type of training to be conducted, environmental issues, health and safety of participants, anticipated duty cycle (i.e., frequency and duration of training activity) and life-cycle cost (e.g., initial purchase price, ongoing maintenance costs).

Figure 1. Live Fire Simulation with Gas (left) and Class A Fuel (right)

As illustrated in Figure 1, there can be obvious and substantial differences in physical fidelity when gas fired props are used to simulate a typical compartment fire. Depending on the purpose of the simulation these physical differences can be important. However, differences in functional fidelity may be even more important.

Functional Fidelity

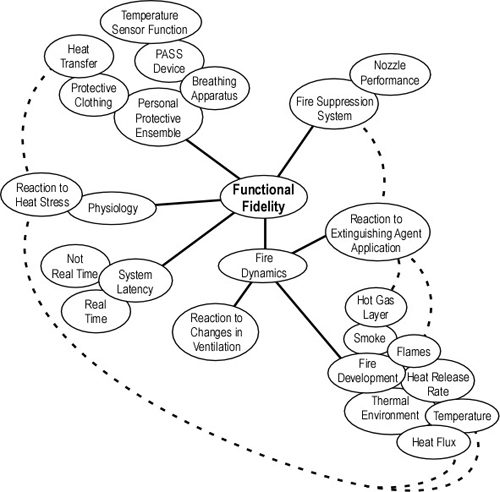

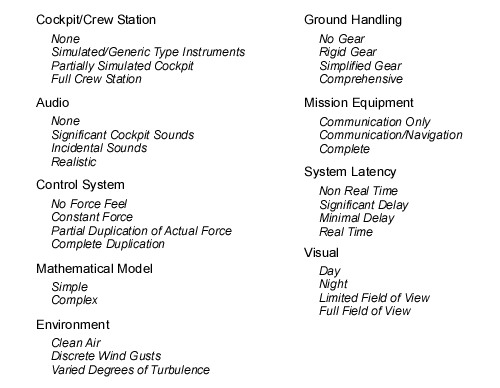

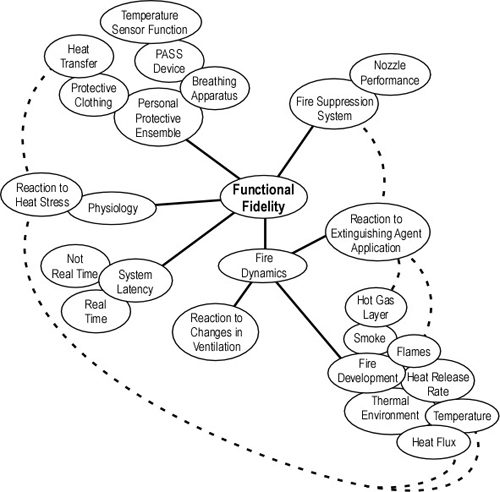

As stated earlier, functional fidelity is the extent to which the simulation works and reacts realistically. I have tentatively identified five subsystems related to functional fidelity of live fire simulation as illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Functional Fidelity Concept Map

This concept map is a simple and preliminary look at the elements of functional fidelity. Each of the concepts illustrated can be further refined and elaborated on to provide a clearer picture of physical fidelity in live fire training.

Physiology & Personal Protective Ensemble

Live fire simulation places the participant in a hostile environment requiring the use of personal protective clothing and self-contained breathing apparatus. Functional fidelity in these subsystems and their interaction with the thermal environment may or may not be a critical element of context, depending on the intended learning outcomes of the simulation. However, insulation of firefighters from the thermal environment encountered in structural firefighting delays, modifies, and my limit perception of critical thermal cues (e.g., high temperature, changes in temperature). Overcoming this challenge requires training in a realistic thermal context.

Fire Suppression System

One of the most critical elements in functional fidelity of the fire suppression system involves interaction with fire dynamics: Does the fire and fire environment (e.g., hot gas layer) react appropriately to extinguishing agent application? In some respects there may be a conflict between the desire for physical fidelity of the fire suppression system and functional fidelity of the interaction between extinguishing agent application and fire dynamics. For example, it may be desirable for participants to use the same flow rate (providing realistic nozzle reaction) in simulations as will be used in the structural firefighting environment. However, the limited fuel load typically used to provide a safe training environment do not result in the same required flow rate for fire control as fire in a typical residential or commercial compartment. Does use of a high flow handline in live fire simulation with limited fuel load create an unrealistic expectation of the performance under actual incident conditions? Which is more effective, realistic flow rate with a limited fuel load or matching of flow rate and fuel load to provide a realistic interaction between the fire and fire attack? This question remains to be answered.

The type of nozzle used presents a simpler issue related to functional fidelity in live fire simulation. Most combination nozzles have similar operational controls for controlling the flow of water (i.e. on and off) and pattern adjustment. However, there are subtle differences such as the extent of movement needed to adjust from straight stream to wide angle fog. Flow control mechanisms vary more widely from fixed flow rate, to variable flow and automatic nozzles. Firefighters must be able to select pattern and flow as necessary based on conditions encountered in the fire environment and intended method of water application. Use of a substantively different nozzle in training than during incident operations is likely to result in less than optimal performance. However, as with the question of flow rate, the extent to which this is a concern is unknown.

Fire Dynamics

Likely the greatest concerns with regards to functional fidelity are in the area of fire dynamics. If firefighters are to learn how fires develop and the impact of changes to ventilation profile and application of extinguishing agents, the fire must behave as it would under actual incident conditions (or as close to this ideal as can be safely and practically accomplished).

Most fuels encountered in structure fires are solids (e.g., furniture, interior finish, structural materials). Class A fuel used in live fire training, often has a lower heat of combustion and heat release rate than typical fuel in the built environment, but is similar in that it must undergo pyrolysis in order to burn; providing similar (but not identical) combustion performance. Combustion of Class A fuel also results in generation of significant smoke, another similarity to typical fuels in the built environment. Class B (gas) fuel used in structure fire simulations has a high heat of combustion with heat release rate controlled through engineering and design of the burner system. However, this fuel generally burns cleanly, necessitating introduction of artificial smoke to provide higher fidelity. Flaming combustion and smoke production must be mechanically controlled by a computerized system, a human operator, or both. The nature of the fuel and design of the combustion system also impact on the fires reaction to changes in ventilation and application of extinguishing agents such as water.

Changes to ventilation will not substantively influence fire behavior if the fire is fuel controlled. However, if the fire is ventilation controlled, changes in ventilation can have a significant impact on fire behavior (which may or may not be desirable, depending on the intended learning outcomes).

With Class A fuel, water applied to cool the hot gas layer or to fuel packages has a similar impact as it would in actual structural firefighting operations. The degree of similarity is dependent on the design of the compartment in which the training is being conducted as well as fuel factors and ventilation profile. With Class B fuel, temperature sensors, computerized controls, and a human operator all must interact to ensure that water application results in appropriate changes to combustion.

System Latency

In general, live fire training simulations are conducted in real time. However, time lag due to system limitations in Class B (gas) fired props or delay in instructor or operator perception of changing conditions in either Class A or B fueled props can influence system latency, resulting in faster or slower than normal interaction between fire dynamics and fire control subsystems.

Closing Thoughts

While I admit I am (currently) biased in favor of live fire training simulation using Class A fuel, there is no reason why other systems such as those using Class B (gas) fuel could not be designed in such a way to provide higher fidelity. However, this would likely increase both complexity and cost. I have been also discussing the potential of computer based (non-live-fire) fire training systems to develop some (but likely not all) of the skills necessary to safely operate in the structural firefighting environment. This is something else to think about!

I will come back to this topic again from time to time as I gain additional insight into the elements of physical and functional fidelity in live fire training.

Remember the Past

Last Tuesday, was the second anniversary of the deaths of Captain Mathew Burton and Engineer Scott Desmond of the Contra Costa County Fire Protection District in California.

Figure 1. 149 Michele Drive-Alpha/Delta Corner

Note: Contra Costa Fire Protection District (Firefighter Q76) Photo, Investigation Report: Michele Drive Line of Duty Deaths. This photo illustrates conditions shortly after 0159 (Q76 time of arrival).

July 21, 2007

Captain Matthew Charles Burton

Fire Engineer Scott Peter Desmond

Contra Costa County Fire Protection District, California

Captain Burton, Engineer Desmond, and another engineer were the crew of Engine 70. At 0143 hours, Engine 70 was dispatched to a residential fire alarm. As additional information was received, the incident was upgraded to a structural fire response with the addition of two engines, a quint, and a command officer.

Engine 70 arrived on the scene at 0150 hours and reported heavy fire and smoke from a small single-family residence. Firefighters reported that they had confirmed reports that two occupants of the home were still inside.

Captain Burton and Engineer Desmond advanced an attack line into the structure and flowed water on the fire. They reported that the fire had been knocked down and requested ventilation at 0155 hours. Captain Burton and Engineer Desmond exited the structure temporarily to retrieve a TIC, then re-entered the structure and went to the left toward the bedrooms with an attack line, while another crew went to the right without an attack line.

The engineer for Engine 70 placed a PPV fan at the front door. One of the civilian fire victims was located by the crew that had gone to the right; her removal was difficult and firefighters had to exit the building to ask for help. During this time, the fire inside the house advanced rapidly.

Firefighters had difficulty venting the roof due to multiple roofs, built-up roofing materials, and the type of construction.

A command officer arrived on the scene at approximately 0202 hours and began to look for Captain Burton to assume Command. The command officer tried to contact the Engine 70 crew by radio but was unsuccessful. A second alarm was requested, and a report of a missing firefighter was transmitted at approximately 0205 hours.

The fire had advanced within the structure and had to be controlled before firefighters could search for the missing crew. Captain Burton and Engineer Desmond were located and removed from the structure between 0212 and 0226 hours. The firefighters were found in a bedroom.

For additional information, see my earlier posts on this incident, the Contra Costa County Fire District Investigative Report, and National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) Death in the Line of Duty Report.

Contra Costa County LODD: Part 1

Contra Costa County LODD: Part 2

Contra Costa County LODD: What Happened

Contra Costa County Fire Protection District Investigation Report: Michele Drive Line of Duty Deaths

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) Death in the Line of Duty Report F2007-28

Ed Hartin, MS, EFO, MIFireE, CFO