Pennsylvania Duplex Fire LODD

Firefighting & Firefighter Rescue Operations

Monday, December 22nd, 2008

This post continues examination of NIOSH Death in the Line of Duty Report F2008-06. My previous post, Developing & Using Case Studies: Pennsylvania Duplex Fire Line of Duty Death (LODD) emphasized the importance of case studies to individual and organizational learning and presented initial information about the incident which resulted in injury to Lieutenant Scott King and the death of Firefighter Brad Holmes of Pine Township Engine Company.

Figure 1. 132 Garden Avenue-Side Alpha

Note: Fire Department Photo – NIOSH Death in the Line of Duty Report F2008-06. This photo likely illustrates conditions after 0635 (approximately 19 minutes after arrival of the first fire unit, Chief 95).

Firefighting Operations

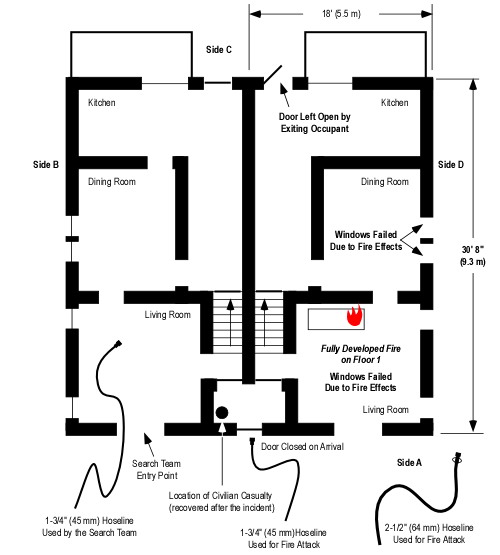

Command assigned Engine 95 (officer and five firefighters) to fire suppression. They deployed a 1-3/4″ť (45 mm) line to the door on Side A, but were unable to make entry due to the volume of fire in the involved unit. Engine 95 also deployed a 2-1/2″ť (64 mm) handline to the A/D corner. Both lines were immediately placed into operation. NIOSH Report F2008-06 indicated that the 1-3/4″ť line stretched to the door on Side A was “unable to make entry due to heavy fire conditions”ť. However, exact placement and operation of the 2-1/2” handline was not specified. This line may have been used to protect Exposure D (a wood frame dwelling approximately 20′ from the fire unit), for defensive fire attack through first floor windows, or both.

Figure 2. Fire Unit and Exposure Bravo Floor 1

Note: This floor plan is based on data provided in NIOSH Report F2008-06 and is not drawn to scale. Windows shown as open are based on the narrative or photographic evidence. Door position is as shown based on information provided by NIOSH Investigator Steve Berardinelli (this differs from the NIOSH report which includes the fire investigators rough sketch showing all doors open). Windows shown as intact are not visible in the available photographs, but may be open due to fire effects or firefighting operations (particularly those in the fire unit).

Second due, Engine 95-2 performed a forward lay from a nearby hydrant and supplied Engine 95 with tank water while waiting for the supply line to be charged.

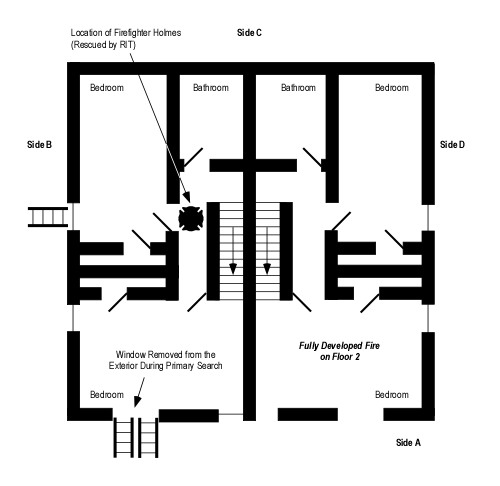

Engine 85 (chief, lieutenant, and three firefighters) was assigned to primary search and rescue of the trapped occupant. Tasked to conduct primary search in Exposure B, Firefighter Holmes and Lieutenant King were performed a 360o reconnaissance prior to making entry. While this was being done other members of the company placed a ladder to a window on Floor 2 Side B (see Figure 3). The NIOSH Report does not specify if the search team was aware of ladder placement.

The Officer of Engine 95 vented the window on Floor 1 Side A of Exposure Bravo and observed that the ceiling light was on (indicating that there was limited optical density of the smoke on Floor 1 of the exposure). Firefighter Holmes and Lieutenant King entered through this window (see Figure 2) to conduct primary search of the exposure and observed that the temperature was low and there was limited smoke on Floor 1. Engine 95 passed the search team a 1-3/4″ť (45 mm) handline through the window and the search team knocked down visible fire extension and completed their search of the first floor. At this point, Firefighter Holmes and Lieutenant King left the hoseline on Floor 1, went up the stairs to Floor 2 and began a left hand search.

Figure 3. Fire Unit and Exposure Bravo Floor 2

Note: See the prior comments regarding windows and door position.

The Officer of Engine 95 noticed that the search crew had finished their search on the first floor and were advancing to the second floor. He placed a ladder and broke the window on Floor 2, Side A (See Figure 3). He stated that there was not much heat on the second floor because the plastic insulation on the window was not melted, but he did notice heavy black smoke beginning to bank down. The NIOSH Report did not specify the depth of the hot gas layer (down from the ceiling) or the air track at the window that was vented or Floor 1 openings (windows and door).

The hydrant that Engine 95-2 laid in from was frozen as was the hydrant several houses beyond the fire buildingFirst alarm companies used tank water to support initial firefighting operations. The crew from Engine 95-2 began to hand stretch a 3″ť line to a working hydrant on a nearby cross street.

After Firefighter Holmes and Lieutenant King partially completed their search of Floor 2, Lieutenant King’s air supply was at one half and Firefighter Holmes was unsure of his air status, so the Lieutenant decided to exit. At approximately the same time, Engine 95 ran out of water and the Command ordered companies to abandon the building with Engine 85 sounding its air horn as an audible signal to do so. The Accountability Officer called for a Personnel Accountability Report (PAR), but received no response from Lieutenant King or Firefighter Holmes.

Almost immediately after Engine 95 ran out of water, conditions changed rapidly decreasing visibility and increasing temperature on Floor 2 of Exposure B and fire involvement of Floors 1 and 2 of both units. With deteriorating conditions on the second floor, Lieutenant King became disoriented and separated from Firefighter Holmes. He radioed for help at 0638 hours. “Help! Help! Help! I’m trapped on the second floor!” In a second radio transmission, Lieutenant King indicated he was at a window on Side D.

Firefighter Rescue Operations

After hearing radio traffic that the search crew could not find their way out and they were by a window the Engine 95 officer accessed a window on Side B Floor 2 (using a ladder previously placed by Engine 85-2). He broke out the window to increase ventilation and attempt contact with the search team.

A crew from Engine 77 was tasked as a second search team and preparing for entry when the IC ordered companies to withdraw. However, when they heard the Lieutenant’s call for help, they immediately went to Side D, not seeing the Lieutenant at the window, they continued to Side B. The officer from Engine 77 climbed the ladder they had placed earlier to attempt contact with the initial search team. There was heavy black smoke coming from this window, but no fire. He straddled the window sill attempting to hear any movement, a PASS device, or voices. He banged on the window sill as an audible signal to the search team, but received no response. He also attempted to locate the search team using a TIC, however, it malfunctioned.

Flames now pushing out the first floor windows of both the unit originally involved in fire as well as Exposure B. Lieutenant King managed to find his way to the staircase, stumbled down the stairs and out the door on Side A. His protective clothing was severely damaged and smoldering. He collapsed in the front yard and told the other firefighters that the victim was trapped on the second floor. The RIT (R87) made entry supported by a hoseline operated from the entry point by Engine 85-2. Firefighter Holmes was located approximately 10′ (3 m) from the top of the stairs (as illustrated in Figure 3). He was semi-conscious and on his hands and knees. The RIT removed Firefighter Holmes via the stairway to Side A. Lieutenant King and Firefighter Holmes were transported to a local hospital where they were stabilized prior to transport to the Mercy Hospital’s Burn Unit in Pittsburgh.

Questions

The following questions provide a basis for examining the second segment of this case study. While limited information is provided in the case, this is similar to an actual incident in that you seldom have all of the information you want.

- What was the stage of fire development and burning regime in the fire unit when the search team entered the exposure?

- What Building, Smoke, Air Track, Heat, and Flame (B-SAHF) indictors can be observed in Figure 1?

- What was the stage of fire development and burning regime in Exposure B when the search team entered?

- What type of extreme fire behavior event occurred in the exposure, trapping Firefighter Holmes and Lieutenant King? What leads you to this conclusion?

- What were the likely causal and contributing factors that resulted in occurrence of the extreme fire behavior that entrapped the Firefighter Holmes and Lieutenant King?

- What self-protection actions might the search team have taken once conditions on Floor 2 of Exposure B began to become untenable?

- What action could have been taken to reduce the potential for extreme fire behavior and maintain tenable conditions in Exposure B during primary search operations?

- What was the tactical rate of flow for full involvement of a single unit in this building? (The tactical rate of flow is the flow required for fire control and does not include the flow rate for backup lines.)

- What factors may have influenced the limited effectiveness of the 1-3/4” and 2-1/2” attack lines deployed by Engine 95?

- What tactical options might have improved the effectiveness of fire control operations given the available water supply?

My next post will examine the contributing factors and recommendations made in NIOSH Death in the Line of Duty Report F2008-06 and will include a link to a more detailed written case study of this incident in PDF format.

Ed Hartin, MS, EFO, MIFireE, CFO