Applying NIOSH Recommendations

NIOSH Death in the Line of Duty reports generally contain two types of recommendations, those that focus on specific contributory factors and others that address general good practice. As when examining contributory factors, it is important to read the NIOSH recommendations critically. Do you agree or disagree and why? What would you change and what additional recommendations would you make based on the information presented in the report?

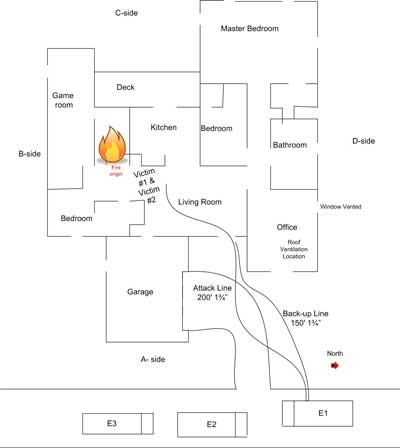

Brief Review of the Incident

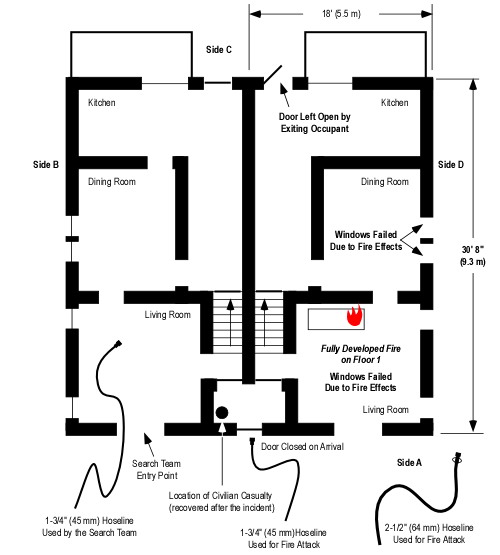

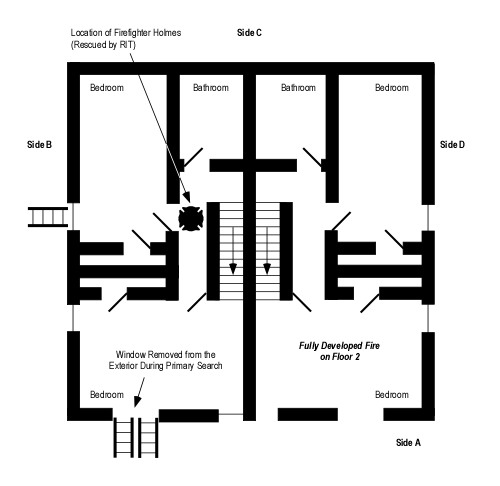

NIOSH Report F2008-06 examines a fire in a wood frame duplex that resulted in injury to Lieutenant Scott King and the death of Firefighter Brad Holmes of the Pine Township Engine Company. The fire occurred on February 29, 2008 in Grove City, Pennsylvania.

When the fire department arrived, the unit on Side D was substantially involved and a female occupant was reported trapped in the building. Initial operations focused on fire control and primary search of Exposure B. Rapid fire development trapped Lieutenant King and Firefighter Holmes while they were searching Floor 2 of Exposure B.

The following photographs are part of a series of 37 pictures taken during this incident and provided to NIOSH investigators during their investigation.

Additional detail on this incident is provided in Developing & Using Case Studies: Pennsylvania Duplex Fire Line of Duty Death (LODD) and Pennsylvania Duplex Fire: Firefighting & Firefighter Rescue Operations . In addition, readers should review NIOSH Report F2008-06.

Recommendations

NIOSH Report F2008-06 contains 11 recommendations. Several of these recommendations are well grounded in the contributory factors identified in the report. Others have a more indirect relationship to the factors influencing the injury to Lieutenant King and death of Firefighter Holmes.

Recommendation #1: Fire departments should be prepared to use alternative water supplies during cold temperatures in areas where hydrants are prone to freezing.

In preparation for potential issues, fire departments should develop standard operating procedures (SOPs) for temporary water sources to be dispatched like tankers, water shuttles, or portable drop tanks.

While this recommendation is valid and good practice, it has little to do with loss of water as a contributory and likely causal factor in the injury to Lieutenant King and death of Firefighter Holmes. Had Command been notified immediately of the frozen hydrant and implemented alternate water supply strategies, the outcome would have likely been the same if tank water had been used as it was in this incident to sustain initial operations.

However, it is critical for fire departments to have a plan to respond to respond to water supply problems. In this case, apparatus had substantial tank water which was used to support initial firefighting operations. In addition, there was sufficient hose available on first alarm companies to stretch to other hydrants (such as the one eventually used east of Garden Avenue on Craig Street). Use of a reverse lay to establish water supply allows the apparatus operator to continue the lay to the next hydrant (hose capacity permitting) or another apparatus to continue the lay and establish a relay. Depending on the distance to the next operational water source, this could be considerably more efficient and rapid than waiting for greater alarm resources to establish a tender shuttle.

Recommendation #2: Fire departments should ensure that search and rescue crews advance or are protected with a charged hoseline.

This recommendation is critical. However, the discussion fails to speak to the need for backup lines to protect the means of egress when crews are working above the fire. Recent incidents in Loudoun County, Virginia and Sacramento California, resulted in crews with a hoseline working above the fire without a backup line having their hose burn through, and means of egress cut off, necessitating emergency egress via second floor windows.

Recommendation #3: Fire departments should ensure fire fighters are trained in the tactics of a defensive search.

While training in search under marginal circumstances is important, this recommendation fails to speak to the need to understand fire behavior and applied fire dynamics as a foundation for maintaining situational awareness on the fireground. This applies to command personnel, company officers, and individual firefighters. While there are a number of points in the sequence of events that lead to Lieutenant King’s injury and Firefighter Holmes’s death, all are dependent on this. Failure to recognize the potential for extension and rapid fire progress, the influence of creating ventilation openings on Floor 2, and recognition of developing fire conditions were likely the most significant causal factor in this incident. Had this not been the case, the firefighters and officers involved would have had the opportunity to adjust their tactical operations or exit the building prior to the occurrence of the extreme fire behavior that trapped the search team.

NIOSH Report F2008-06 quotes Deputy Chief Vincent Dunn regarding flashover indicators:

There are two warning signs that may precede flashover: heat mixed with smoke and rollover. When heat mixes with smoke, it forces a fire fighter to crouch down on his hands and knees… As mentioned above, rollover presages flashover.

This statement is scientifically incorrect. Heat is simply energy in transit due to temperature difference. It is not a substance and cannot mix with anything else. Increasing temperature is an indicator of potential for flashover, but perception of a rapid increase in temperature is not certain to give adequate warning to take corrective action or escape from the hazardous situation. In addition, rollover does not always precede flashover (it is an important indicator, but only one of many).

The report also quotes Chief Dunn regarding defensive search tactics.

Three defensive search tactics are as follows:

- At a door to a burning room that may flashover, fire fighters should check behind the door to the room and sweep the floor near the doorway. Fire fighters should not enter the room until a hose line is in position.

- When there is a danger of flashover, fire fighters should not go beyond the “point of no return.” The point of no return is the maximum distance that a fully equipped fire fighter can crawl inside a superheated, smoke-filled room and still escape alive if a flashover occurs. The point of no return is approximately five feet inside a doorway or window.

- When searching from a ladder tip placed at a window, look for signs of rollover if one of the panes has been broken. If rollover is present, do not go through the window. Instead, crouch below the heat and sweep the interior area below the windowsill with a tool. If a victim has collapsed there, you may be able to crouch below the heat enough to pull him to safety.

While these tactics have validity, making for search without without protection of a hoseline even to Chief Dunn’s “point of no return”ť presents a significant risk. Further, I am uncertain that there is any scientific evidence supporting the concept of the point of no return as described by Chief Dunn. There are numerous examples of situations where firefighters thought they had time to complete a search, but were trapped by extremely rapid fire development. The risk of searching under marginal conditions requires firefighters to effectively read the fire and mitigate hazards in the fire environment through effective use of gas cooling and control of the ventilation profile (either tactical ventilation or anti-ventilation as appropriate) and establishing fire control in addition to primary search.

Recommendation #4: Fire departments should ensure that fire fighters conducting an interior search have a thermal imaging camera.

The thermal imaging camera is a tremendous technological innovation which can significantly speed search operations and provide visual indication of differences in thermal conditions. However, implementation of this recommendation would not necessarily have impacted on the outcome of this incident.

Recommendation #5: Fire departments should ensure ventilation is coordinated with interior fireground operations.

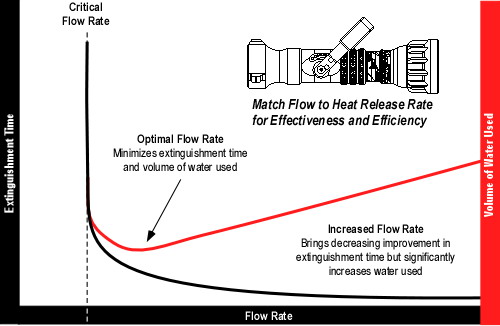

In the discussion of this recommendation, the NIOSH Report F2008-6 states “By eliminating smoke, heat, and gases from the fire it will help minimize flashover conditions”ť

This statement is not always true. The influence of ventilation on fire development is dependent on burning regime (fuel or ventilation controlled) and the location of the inlet and exhaust openings. Heat release rate from a ventilation controlled fire will increase as ventilation is increased, potentially taking the fire to flashover (rather than the reverse as indicated by the statement in this NIOSH report). In addition, creation of an air track that channels the spread of hot gases and flames to additional fuel packages can result in fire extension and subsequent flashover. Both of these factors were likely to have been significant in this incident. Coordination of ventilation and search or ventilation and fire attack (as frequently stated in NIOSH reports related to incidents involving extreme fire behavior) requires knowledge of fire dynamics and the influence of ventilation in fire behavior.

Recommendation #6: Fire departments should ensure that Mayday protocols are developed and followed.

This recommendation is important, but fails to address other individual level survival skills that must be integrated with these procedures. For example, in this incident, the Lieutenant and Firefighter might have been able to take refuge in one of the bedrooms, closing the door to provide a barrier to hot gases and flames. A ladder was initially placed to a window in the bedroom on Side B (in close proximity to the location where Firefighter Holmes was found). Ladders were subsequently placed to the bedroom windows on Side A. While it may have been difficult to accomplish this under conditions of extreme thermal insult, if developing conditions had been recognized soon enough (see my earlier observation on situational awareness), this may have bought critical seconds and allowed the trapped search team to escape or be rescued.

Recommendation #7: Fire departments should ensure that the Incident Commander receives pertinent information during the size-up (i.e., type of structure, number of occupants in the structure, etc.) from occupants on scene and that information is relayed to crews upon arrival.

Had the Incident Commander received more specific information from the occupants or law enforcement, this may have shifted focus in search operations as survivability in the original fire unit was doubtful. Despite this, the civilian casualty was later located outside the fire unit, behind the door in the front foyer that served both dwelling units.

Recommendation #8: Fire departments should ensure that fire fighters communicate interior conditions and progress reports to the Incident Commander.

This is a key element in maintaining situational awareness (on the part of the Incident Commander). However, it is equally important for Command to communicate with interior crews regarding conditions observed from the exterior or situations (such as water supply limitations) that will impact interior operations.

Recommendation #9: Fire departments should develop, implement, and enforce written standard operating procedures (SOPs) for fireground operations.

This recommendation focuses on general good practice, but is not tied to specific contributing factors related to the injuries and fatality that resulted in this incident. This type of recommendation should likely be included, but placed in a separate section so as not to dilute the focus on lessons learned.

Recommendation #10: Fire departments and municipalities should ensure that local citizens are provided with information on fire prevention and the need to report emergency situations as soon as possible to the proper authorities.

Recommendation #11: Building owners and occupants should install smoke detectors and ensure that they are operating properly.

If implemented prior to this incident, Recommendations #10 and #11 would likely have had a positive impact on its outcome, particularly with regards to the civilian casualty and the severity of conditions encountered by the firefighters.

However, these two recommendations do not go far enough. Citizens must also recognize the need for rapid egress and the value of closing doors to confine the fire and limit inlet of air required for continued fire development and increasing heat release rate.

Detailed Case Study

CFBT-US has developed a detailed case study based on this incident and the data contained in NIOSH Report F2008-06. Download the Grove City, Pennsylvania Residential (Duplex) Fire Case Study in PDF format.

Now What?

Over the last two weeks we have spent considerable time with a NIOSH Report F2008-06. NIOSH has completed 335 investigations during the first 8 years that this program has been in existence. 49 more investigations are pending. The information contained in these reports provides a vast reservoir of data that can be used to deepen understanding of your craft and improve decision-making and risk management skills.

Make a commitment to developing your expertise as a firefighter or fire officer in the new year and for the rest of your life. Look for the this logo (more information to follow)!

Have a safe and happy new year!

Ed Hartin, MS, EFO, MIFIreE, CFO