Contra Costa County LODD

Thursday, May 7th, 2009As discussed in previous posts, developing mastery of the craft of firefighting requires experience. However, it is unlikely that we will develop the base of knowledge required simply by responding to incidents. Case studies provide an effective means to build our knowledge base using incidents experienced by others.

Introduction

The deaths of Captain Matthew Burton and Engineer Scott Desmond in a residential fire were the result of a complex web of circumstances, actions, and events. This case study was developed using the Contra Costa County Fire Protection District Investigative Report and NIOSH Death in the Line of Duty Report 2007-28 and video taken by a Firefighter assigned to Quint 76 (Q76), the first alarm truck company. This case study focuses on the fire behavior and related tactical operations involved in this incident. However, there are a number of other lessons that may be learned from this incident and readers are encouraged to review both the fire district’s investigation and NIOSH report for additional information.

The Case

Early on the morning of July 21, 2007, Captain Matthew Burton and Engineer Scott Desmond were performing primary search of a single family dwelling in San Pablo, California. During their search, they were trapped by rapidly deteriorating conditions and died as a result of thermal injuries and smoke inhalation. Two civilian occupants also perished in the fire.

Figure 1. 149 Michele Drive-Alpha/Delta Corner

Note: Contra Costa Fire Protection District (Firefighter Q76) Photo, Investigation Report: Michele Drive Line of Duty Deaths. This photo illustrates conditions shortly after 0159 (Q76 time of arrival).

Building Information

The fire occurred in a 1,224 ft2 (113.7 M2), one-story, wood frame dwelling with an attached garage at 149 Michele Drive in San Pablo (Contra Costa County), California. The house was originally built in 1953 and remodeled in 1991 with the addition of a pitched rain roof over the original (flat) roof.

This single story structure was of Type V, platform frame construction. The building was originally constructed with 4″ x 8″ (102 mm x 203 mm) beams supporting a flat roof with 2″ x 6″ (51 mm x 152 mm) tongue and groove planking with a built-up overlay consisting of several layers of tar and gravel. The pitched roof was constructed of 2″ x 8″ (51 mm x 203 mm) rafters covered with plywood and asphalt composite shingles. The ridge of the pitched roof was parallel to Side A. The gable ends on Sides B and D were constructed of plywood and fitted with a small gable vent.

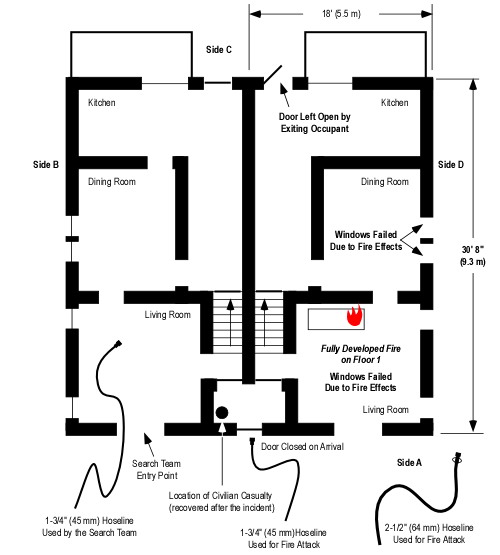

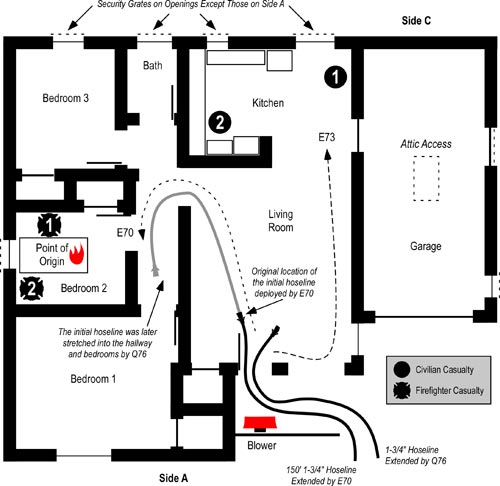

Figure 2. Floor Plan-149 Michelle Drive

Note: This floor plan is based on data provided in the Contra Costa Fire Protection District Investigation Report and is not drawn to scale. The position of exterior doors and condition of windows as illustrated is based on the narrative or photographic evidence. Interior doors are shown as open as illustrated in the report. Fire service casualties are designated as follows: 1) Captain Burton, 2) Engineer Desmond.

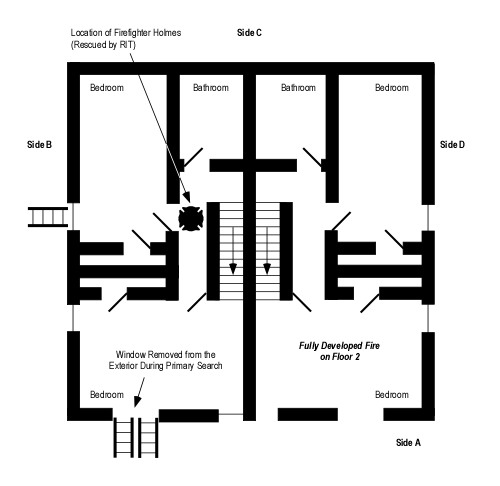

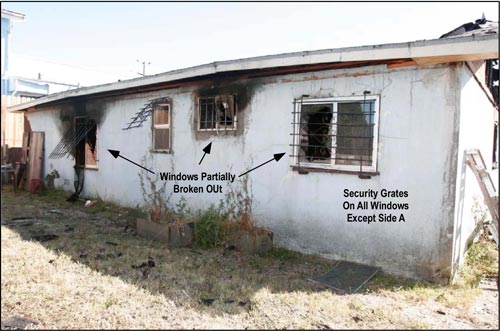

All windows with the exception of the Living Room and Bedroom 1 (see Figure 2) were fitted with security bars (see Figure 3). The front door was the primary exit. In addition, an additional exit was provided from the kitchen through the garage to the exterior on Side D. The exterior door on Side D was fitted with a security grate.

Figure 3. View of Side C from the B/C Corner

Figure 4. Hallway and Bedroom 2

Note: Figures 3 & 4 adapted from Contra Costa Fire Protection District Photos (brightness and contrast adjusted to provide increased clarity).

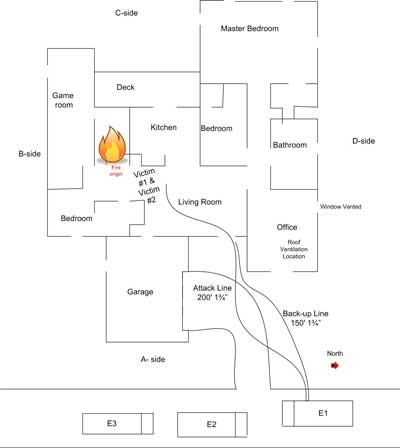

Interior walls were gypsum board with wood veneer paneling on some of the walls (e.g., living room). All ceilings with the exception of the kitchen were exposed 2″ x 6″ (51 mm x 152 mm) tongue and groove planking (see Figure 4). The kitchen ceiling was covered with gypsum board. Ceiling height was 8′ (2.4 M).

Figure 5. Living Room

Note: Adapted from Contra Costa Fire Protection District Photos, Investigation Report: Michele Drive Line of Duty Deaths.

The Fire

Investigators determined that the fire likely originated on or near the east end of the bed in Bedroom 2 (see Figures 2 & 3). The likely source of ignition was improper discard of smoking materials. Developing into growth stage, the fire progressed from Bedroom 2 into the hallway (see Figures 2 & 4) leading to the living room, dining area, and kitchen (see Figures 2 & 5). It is likely that the door on Side A was closed at the time of ignition, but was opened by an occupant exiting some time after discovery of the fire.

Dispatch Information

Occupants discovered the fire and notified a private alarm company via two-way intercom at 0134. The alarm company notified the Contra Costa Regional Fire Communications Center of receipt of a fire alarm from 149 Michelle Drive at 0136 using the non-emergency telephone number. The alarm company did not indicate that they had talked to the resident who had reported a fire, but simply that they had received a fire alarm. The caller was placed on hold due to a higher priority 911 call. The dispatcher returned to the call from the alarm company at 0142 to obtain the address and callback information. Two attempts were made to call the incident location prior to dispatch of Engine 70 at 0144 to investigate the alarm. Contra Costa County Fire Protection District (CCCFPD) Engine 70 responded at 0145.

Shortly after Engine 70 responded, the communications center received a cell phone call from the female occupant at 149 Michelle Drive. This call was originally received by the California Highway Patrol and transferred to Contra Costa County Regional Fire Communications Center. The caller reported a residential fire and indicated that she had not been able to get her husband out of the building. Between the time that she spoke to the dispatcher and arrival of Engine 70, the female occupant reentered the building to attempt to rescue her husband (leaving the door on Side A open).

At 0146, the dispatcher upgraded the response to a residential fire and added two additional engines, a quint (as the truck company), and a battalion chief. Subsequent to the upgrade to a residential fire, additional 911 calls were received reporting a residential fire at 149 Michelle Drive.

Resources dispatched on the first alarm were as follows: Engine 70 (already responding on the initial dispatch for a residential alarm), Engine 69 (CCCFPD) as well as Rodeo-Hercules Fire Protection District Quint 76, and Battalion 7. Richmond Fire Department Engine 68 was requested for automatic aid response through the Richmond Communications Center to fill out the first alarm assignment. Pinole Fire Department Engine 73 cleared a medical call a short distance away from the incident location and added themselves to the first alarm assignment. With the addition of Engine 73, the dispatcher canceled response of Engine 68 through Richmond Dispatch.

Note: Engine 73 was using an apparatus normally assigned at Station 74 which was marked with the designation Engine 74. This created some confusion during initial incident operations.

Weather Conditions

Conditions were clear, temperature was approximately 61o F (16o C), with a south to southeast (Side D to Side B) wind at between 2 and 6 mph (3.2 and 9.7 kph).

Conditions on Arrival

Shortly prior to arrival, Engine 70 reported “smoke showing a block out” and was advised by the dispatcher that the female occupant had been trying to get her husband out of the house and that it was uncertain if she had been successful. Engine 70 arrived at 0150, reported heavy smoke and fire from a single-story residential structure (flames and smoke were exiting from the open front door and large living room window on Side A), and established Command. Due to delays in the dispatch process, the time from the initial auomatic alarm until the arrival of E70 was approximately 16 minutes.(Refer to Contra Costa Fire Protection District, Investigation Report: Michele Drive Line of Duty Deaths for additional information regarding factors influencing the dispatch delay.

Questions

The following questions provide a basis for examining the first segment of this case study. You have an advantage that Captain Burton did not in that you are provided with a floor plan, photographs of Side C and the interior, and have knowledge of the eventual outcome. However, it is important that you place yourself in the situation encountered on arrival.

- What stage(s) of fire and burning regime(s) were present in the building when E70 arrived? Consider potential differences in conditions in the living room, hallway, and bedrooms?

- If you suspect that fire conditions in the living room were different than the hallway and bedrooms, why might this be the case? What evidence supports your position? What are your assumptions?

- While limited information is available about the fire behavior indicators present during this incident, what Building, Smoke, Air Track, Heat, and Flame (B-SAHF) indictors did E70 observe when they arrived?

- What B-SAHF indicators would you anticipate could have been observed on Sides B and C had this reconnaissance been conducted prior to making entry?

- If you were faced with this situation, fire showing from the front door and window of a single family dwelling with persons reported, what actions would you take?

- How do you think your selection of tactics would have influenced fire behavior and interior conditions?

Tactical Operations & Fire Behavior

My next post will examine tactical operations conducted by the first arriving companies and fire behavior encountered inside the building.

Ed Hartin, MS, EFO, MIFireE, CFO

References

Contra Costa County Fire Protection District. (2008). Investigation Report: Michele Drive Line of Duty Deaths. Retrieved February 13, 2009 from http://www.cccfpd.org/press/documents/MICHELE%20LODD%20REPORT%207.17.08.pdf

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (2009). Death in the Line of Duty Report 2007-28. Retrieved May 5, 2009 from http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/fire/pdfs/face200728.pdf.