Public Stakeholder Meeting

On 19 November 2008, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) will conduct a public stakeholder meeting to gather input on the Firefighter Fatality Investigation and Prevention Program. This meeting has a similar focus to one held on 22 March 2006 in Washington DC. At the 2006 stakeholder meeting, NIOSH received Input from a diverse range of fire service stakeholders. Feedback was extremely supportive of the program, but provided input on potential improvements to this extremely important program. In 2006, I gave a brief presentation that focused on several key issues:

- The upward trend in the rate of firefighter fatalities due to trauma during offensive, interior firefighting operations.

- Failure of NIOSH to adequately address fire behavior and limited understanding of fire dynamics as a causal or contributing factor in these fatalities.

The issues that I raised at the 2006 stakeholder meeting continue to be a significant concern. In 2007, extreme fire behavior was a causal or contributing factor in 17 firefighter line of duty deaths (LODD) in the United States. Where these incidents were investigated by NIOSH, the investigations, subsequent reports, and recommendations did not substantively address the fire behavior phenomena involved nor did they provide recommendations focused on improving firefighters and fire officers understanding of practical fire dynamics.

Ongoing Challenges

In the 20 months since the 2006 stakeholder meeting, NIOSH has implemented a number of stakeholder recommendations. However, Death in the line of duty reports continue to lack sufficient focus on fire behavior and human factors issues contributing to traumatic fatalities during offensive, interior firefighting operations.

Where these reports could provide substantive recommendations for training and operations that would improve firefighter safety, they continue to provide general statements reflecting good practice. While the recommendations contained in NIOSH Death in the line of duty reports, are correct and critically important to safe and effective fireground operations, they frequently provide inadequate guidance and clarity.

In incidents involving extreme fire behavior, investigators frequently fail to adequately address the fire behavior phenomena involved and the implications of the action or inaction of responders. In addition, while training is addressed in terms of national consensus standards or standard state fire training curriculum, there is no investigation as to how the level of training in practical fire dynamics, fire control, and ventilation strategies and tactics may have impacted on decision making.

Presentation of these issues in general terms does not provide sufficient clarity to guide program improvement. Examination of a recent death in the line of duty report will be used to illustrate the limitations of these important investigations and reports in incidents where extreme fire behavior is involved in LODD.

Death in the line of duty… F2007-29

There are many important lessons to be learned from this incident and the limited information presented in this report. However, this analysis of Report F2007-29 focuses on fire behavior and related tactical decision-making. This analysis is completed with all due respect to the individuals and agencies involved in an effort to identify systems issues related to the identification and implementation of lessons learned from firefighter fatalities.

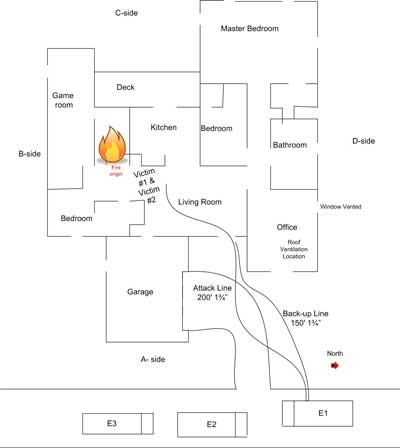

On August 3, 2007 Captain Kevin Williams and Firefighter Austin Cheek of the Noonday Volunteer Fire Department lost their lives while fighting a residential fire. Neither this information nor any reference to the report on Firefighter Fatality Investigation FY 07-02 released by the Texas State Fire Marshal’s Office was included in NIOSH Death in the line of duty report F2007-29. This is critical to locating additional information regarding the incident. Even more importantly, it is important to remember that firefighter LODD involve our brother and sister firefighters, not simply “Victim #1″ť and “Victim #2”.

Reading the Fire

This incident involved a 2700 ft2, wood frame, single family dwelling. The fire was reported at 0136 and the first unit arrived on scene at 0150. The crew of the first arriving engine deployed a 1-3/4″ť (45 mm) hoseline and positive pressure fan to the door on Side A. NIOSH Report F2007-29 reported that the attack team made entry at 0151 but backed out a few minutes later due to flames overhead just inside the front door and that positive pressure was initiated at 0156 prior to the attack team re-entering the building.

However, the Texas State Fire Marshal’s Report FY 07-02 indicated the following:

Flint-Gresham Engine 1 arrived on scene at 01:50:21 positioning short of Side Ať and reported, “On location, flames visible.”ť

Firefighters Joshua Rawlings and Ben Barnard of the Flint-Gresham VFD pulled rack line 2, a 200â long 1.3/4” (45 mm) ť line, to the front door on Side A.ť Flint-Gresham VFD Firefighter Robles conducted a quick survey of the north side and then positioned the vent fan at the front door to initiate Positive Pressure Ventilation (PPV). Robles stated that the PPV was set and operating prior to entry by the first attack team. Robles stated that he started to survey the south side and noted heavy black smoke from the top half of a broken window. He stated that he reported this to the IC.

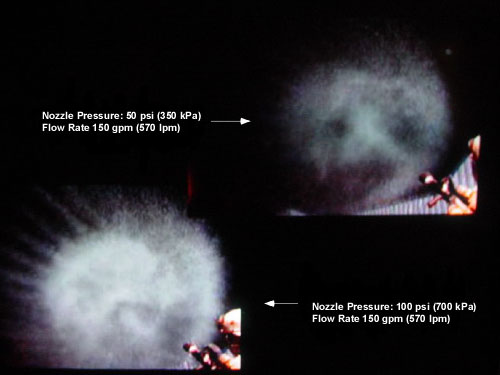

Flint-Gresham Firefighters Barnard (nozzle) and Rawlings (backup) entered through the open front door and advanced 8-10 feet on a left hand search. This attack team noted flames rolling across the ceiling moving from their left to their right as if from the attic. Rawlings stated that flames were coming out of the hallway at the ceiling area and around the corner at a lower level. Barnard reported the hottest area at the hallway. The interior attack team then backed out to the front doorway and discussed their tactics. After a brief conversation, Rawlings took the nozzle with Barnard backing him and they re-entered. They entered approximately 10 feet and encountered flames rolling from their left to their right. They used a “penciling technique”ť aimed at the ceiling to cool the thermal layer. Rawlings reported in interview that there was an increase in heat and decrease in visibility as the thermal layer was disrupted and heat began to drop down on top of them.

There is an inconsistency between the NIOSH and Texas State Fire Marshal’s reports regarding the timing of the positive pressure ventilation. The NIOSH report indicates that positive pressure was applied between the first and second entries by the attack team. However, in the Fire Marshal’s report, Firefighter Robles is quoted as stating that positive pressure was applied before entry. This seems to be a minor point, but if effective, positive pressure ventilation would have significantly changed the fire behavior indicators observed from the exterior and inside the building. Recognition of this discrepancy along with a sound understanding of practical fire dynamics would have pointed to the ineffectiveness of tactical ventilation and potential for extreme fire behavior.

The NIOSH report did not identify the fire behavior indicators initially observed by Firefighter Robles or the attack team, nor did they draw any conclusions regarding the stage of fire development, burning regime (fuel or ventilation controlled), or effectiveness of the positive pressure ventilation.

NIOSH Report F2007-29 did not speak to the fact that none of the first arriving personnel verified the size and adequacy of the existing ventilation opening, the potential implications of inadequate exhaust opening size, and the need to verify that the positive pressure ventilation was effective prior to entry. In addition, the initial attack crew observed flames moving toward the point of entry, which would not be likely if the positive pressure ventilation was effective. However, no mention was made in the NIOSH report regarding conditions inside building and the observations of the attack team.

Window size is not specified, but it is likely that the opening was significantly less than the area of the inlet being pressurized by the fan. Inadequate exhaust opening area leads to excessive turbulence, mixing of hot smoke (fuel) and air, and can lead to extreme fire behavior such as vent induced flashover or backdraft. Recognition of this discrepancy along with a sound understanding of practical fire dynamics would have pointed to the ineffectiveness of tactical ventilation and potential for extreme fire behavior.

In reading this case study, it would be useful for the reader to be able to make a connection between key fire behavior indicators, the decisions made by on-scene personnel, and subsequent fire behavior. The NIOSH report did not identify the indicators initially observed by interior or exterior crews, nor did it draw any conclusions regarding the stage of fire development, burning regime (fuel or ventilation controlled), or effectiveness of the positive pressure ventilation, all of which were likely factors influencing the outcome of this incident.

NIOSH Report F2007-29 indicated that the attack team exited the building at 0213 due to low air and reported that the fire was knocked down, identified the location of a few hot spots, and that smoke conditions were light. The report follows to indicate that one of the chief officers did a walk around two minutes later and observed smoke in all the windows and smoke coming from the B/C and C/D corners of the structure. However the Texas State Fire Marshal’s Report 07-02 stated:

Firefighters Rawlings and Barnard penciled the rolling flames in the thermal layer until Rawlings’s low air alarm sounded. The Incident Commander, Captain Williams and Firefighter Cheek met Firefighters Rawlings and Barnard at the front door and a briefing occurred. Firefighters Rawlings and Barnard reported to Asst. Chief Baldauf they had the hot spots out. Rawlings stated in a later interview that they told Williams and Cheek they knocked down the fire and only overhaul was needed.

At 02:13, Captain Williams and Firefighter Cheek entered the structure as attack team 2, using the same line previously utilized by Firefighters Rawlings and Barnard.

Exterior crews from Noonday and Bullard started horizontal ventilation by breaking a window out on Side C (north side). Noonday Chief Gary Aarant performed a walk around, then reported heavy smoke from the B/C,and C/Dť corners and at 02:15:51 asked if vertical ventilation had been started. Command then gave the order to begin vertical ventilation.

Understanding what occurred in this incident requires more than the cursory information provided in the NIOSH report. Developing the understanding of critical fire behavior indicators is essential to situational awareness. Discussion of fire behavior indicators and their significance in NIOSH reports would provide an excellent learning opportunity. For example, in this incident, the difference between “smoke” as described in the NIOSH report and “heavy smoke” as reported in the Texas State Fire Marshal’s report is likely a significant difference in assessment of conditions from the exterior of the building (particularly if this is a change in conditions).

NIOSH Report F2007-29 made brief mention of smoke discharge from the point of entry which was being used as the inlet for application of positive pressure. “At 0236 hours, heavier and darker smoke began pushing out of the entire front door opening and overriding the PPV fan”. However, the report does not speak to the significance of this indicator of impending extreme fire behavior.

The Texas State Fire Marshal’s Report 07-02 included a series of photographs provided by the Bullard Fire Department which provided a dramatic illustration of these key smoke and air track indicators. Inclusion of these photographs in the NIOSH report would have aided the reader in recognizing this key indicator of ineffective tactical ventilation and imminent potential for extreme fire behavior.

Photo of Conditions on Side A at 0210

Bullard Fire Department Photo/Texas State Fire Marshal’s Report

Photo of Conditions on Side A at 0217

Bullard Fire Department Photo/Texas State Fire Marshal’s Report

Photo of Conditions on Side A at 0223

Bullard Fire Department Photo/Texas State Fire Marshal’s Report

NIOSH Report F2007-29 addresses the need for the incident commander to conduct a risk versus gain analysis prior to and during interior operations. However, the report does not address the foundational skill of being able to read fire and predict likely fire behavior as a part of that process. In addition, reading the fire and dynamic risk assessment are not solely the responsibility of the incident commander. Everyone on the fireground must be involved in this process within the scope of their role and work assignment. For example, the initial and subsequent attack teams were in a position to observe critical indicators that were not visible from the exterior.

While there is no way to tell, it is likely that if Captain Williams and Firefighter Cheek recognized the imminent probability of extreme fire behavior or the significance of changing conditions they would have withdrawn the short distance from their operating position to the exterior of the building. Likewise, if the incident commander or others operating on the exterior recognized deteriorating conditions earlier in the incident it is likely that they would have taken action sooner to withdraw the crew working on the interior.

Understanding practical fire dynamics, recognition of key indicators and predicting likely fire behavior is a critical element in situational awareness and dynamic risk assessment. Fire behavior and fire dynamics receive limited focus in most standard fire training curricula. It is important that NIOSH examine this issue when extreme fire behavior is a causal or contributing factor in LODD.

My next post will continue with the analysis of NIOSH Report F2007-29 and will make specific recommendations for program improvement.

Ed Hartin, MS, EFO, MIFireE, CFO