Fire Gas Ignitions

Thursday, February 26th, 2009What is Extreme?

There is some debate about the use of the term extreme fire behavior (some of my colleagues indicate that processes such as flashover is not “extreme” but simply “normal” fire behavior). I contend that flashover would potentially be a normal part of fire development, but is also extreme, at least in the context that we are using the word. As defined in the wildland firefighting community:

“Extreme” implies a level of fire behavior characteristics that ordinarily precludes methods of direct control action. One or more of the following is usually involved: high rate of spread, prolific crowning and/or spotting, presence of fire whirls, strong convection column. Predictability is difficult because such fires often exercise some degree of influence on their environment and behave erratically, sometimes dangerously (National Wildfire Coordinating Group Glossary)

In the structural firefighting environment, occurrence of flashover (particularly while firefighters are operating inside the compartment) fits substantially with the description of extreme used by wildland firefighters.

Classification and Understanding

Ontology may be described as definition of a formal representation of concepts and the relationships between those concepts. An ontology provides a shared vocabulary. Unfortunately we do not have a well developed ontology of fire behavior phenomenon and many types of phenomena have more than one definition. As with the use of the word extreme, there is some debate about the need to classify phenomena as being this or that (e.g., flashover or backdraft). I take the position that it is useful (but difficult as we do not have a common classification scheme or ontology). But, I think that it is still worth the effort.

This is a substantive topic for a later post. This post will examine a type of fire gas ignition phenomena that has been involved in a number of incidents in recent years resulting in near misses, injuries, and fatalities.

Fire Gas Ignitions

In a previous post, I posed the question: Backdraft or Smoke Explosion?. This post used a video clip to open a discussion of the difference between these two phenomena. A smoke (or fire gas) explosion is a type of fire gas ignition, but there are a number of other types of fire gas ignition that present a hazard during firefighting operations.

All fire gas ignitions (FGI) involve combustion of accumulated unburned pyrolysis products and flammable products of incomplete combustion existing in or transported into a flammable state (Grimwood, Hartin, McDonough, & Raffel, 2005). In a smoke explosion, ignition of a confined mass of smoke gases and air that fall within the flammable range results in extremely rapid combustion (deflagration), producing an significant overpressure which can result in structural damage. However, what happens if the mass of gas phase fuel is not pre-mixed within its flammable range and does not burn explosively?

The general term Fire Gas Ignition, encompasses a number of phenomena that are related by the common characteristic that they involve rapid combustion of gas phase fuel consisting of pyrolizate and unburned products of incomplete combustion that are in or are transported into a flammable state. For now, let’s differentiate these phenomena from backdraft on the basis of the concentration of gas phase fuel (backdraft involving a higher concentration than fire gas ignition).

Fire gas ignition can involve explosive combustion (as in a smoke explosion) or rapid combustion that does not produce the same type of overpressure as an explosion. One such phenomenon is a flash fire. In this case, gas phase fuel ignites and burns for short duration, but does not release sufficient energy for the fire to transition to a fully developed stage (as occurs in flashover). While a flash fire may not result in flashover, the energy release is still significant and heat flux (energy transferred) can be sufficient result in damage to personal protective equipment, injury and death. This post uses a case study to examine the flash fire phenomenon.

Residential Fire

This case study is based on a near-miss incident involving extreme fire behavior during a residential fire that occurred on October 9, 2007 at 1119 William Street in Omaha, Nebraska. Special thanks to Captain Shane Hunter (Omaha Fire Department Training Officer) for sharing this post incident analysis and lessons learned.

Unlike many of the incidents used as case studies, no one died or was injured during incident operations. In this near miss incident, the firefighters and officers involved escaped without injury, but the outcome could easily have been quite different.

Weather Conditions

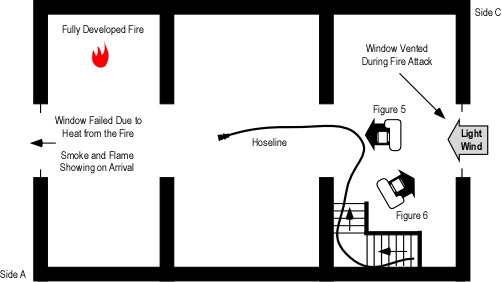

Weather was typical for early fall with a light breeze from the south (blowing towards Side C of the fire building).

Building Information

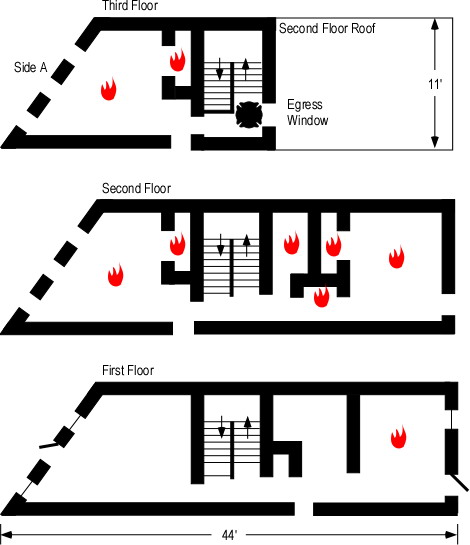

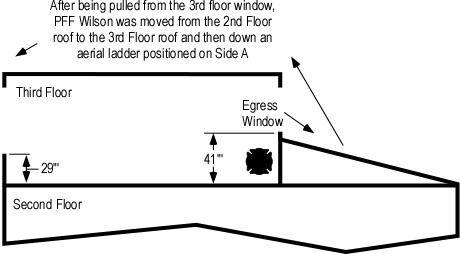

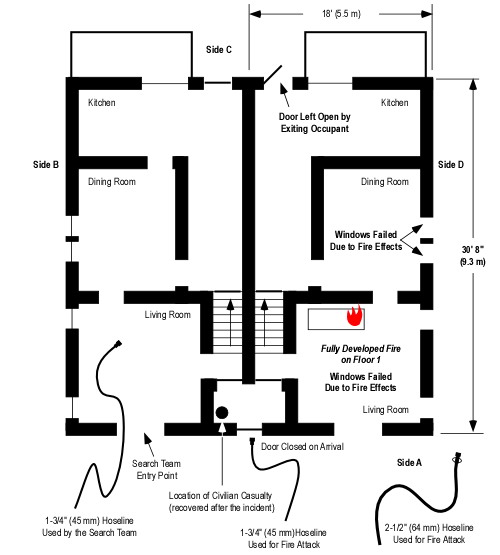

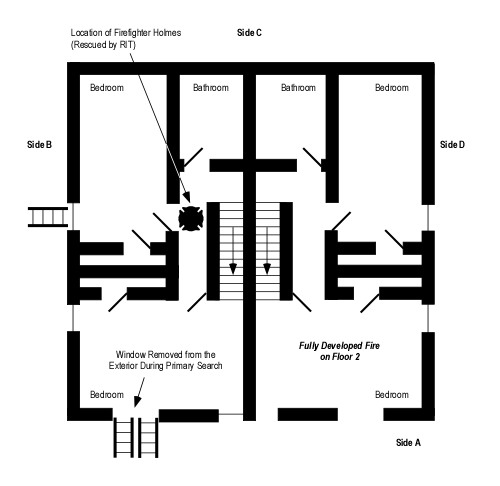

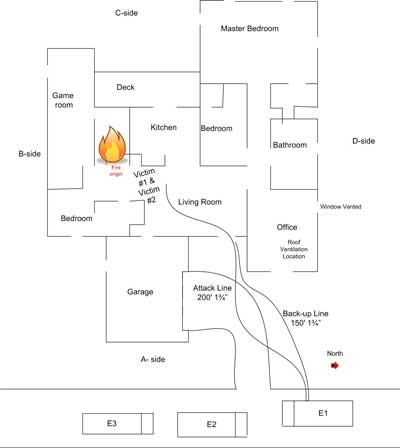

The fire building was a one and a half story, wood frame dwelling with a basement (see Figure 1). The attic space had been renovated into three separate compartments to provide additional living space.

Figure 1. Exterior View Side A

Figure 2. Floor 2 Layout

Conditions on Arrival

When the first company arrived they observed fire and smoke from the second floor window (see Figure 1) and reported a working fire. The doors and windows on the first floor were closed.

Firefighting Operations

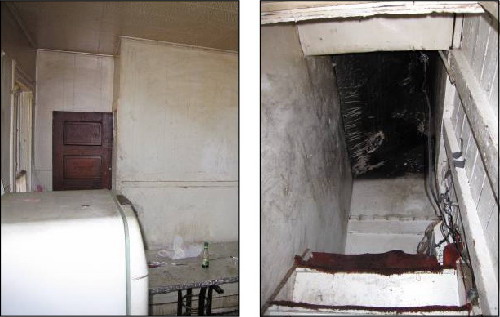

What initial actions were taken? A 200′ hoseline was extended through the door located on Side A and through the living room and kitchen to the stairway to the second floor, which was located at the C/D corner of the structure (Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 5 & 6. Kitchen (view from Floor 1) and Stairwell (view from Floor 2)

What did the fire attack crew observe? The living room and kitchen were clear of smoke and the door to the second floor stairway was closed. When this door was opened and the line was advanced up the stairway to the second floor, the company assigned to fire attack encountered smoke down to floor level on the second floor. Making a left turn at the top of the stairs (see Figure 4) the Captain noted high temperature at the floor level and observed rollover at the ceiling level.

- How did the ventilation profile change when the door to second floor stairway was opened? How might this have changed fire behavior?

- What did the depth of the hot gas layer (from ceiling to floor) indicate about the ventilation profile?

- What did rollover in the center compartment indicate?

The Captain instructed the nozzle operator to apply water to the ceiling. The firefighter on the nozzle applied water in a 30o fog pattern (continuous application). Simultaneously, a crew working on the exterior vented the second floor window on Side C (see Figures 4 and 6).

How did conditions change? The engine company working on floor 2 heard an audible, whoosh as the hot gas layer ignited producing flames down to floor level. Operation of the hoseline (30o fog pattern) had no immediate effect. The Captain ordered the crew to retreat into the stairwell and continue water application.

- What extreme fire behavior phenomena occurred?

- What were the initiating events that caused this rapid fire progression?

Figure 4. Floor 2 Side A (Looking Towards Side A)

Figure 5. Floor 2 Side C (Looking Towards Side C)

What action was taken? While the engine company operated from the stairwell, vertical ventilation was completed over the center compartment (see Figures 4 and 5). After the creation of an exhaust opening in the roof, conditions on floor 2 became tenable and the engine crew was able to knock the fire down within several minutes.

- Why did conditions improve quickly after the creation of a vertical exhaust opening?

- What tactical options might have prevented this near miss?

Observations and Analysis

Captain Shane Hunter observed that the initial fire attack crew viewed this incident as an easy job. They thought that an attack from the unburned side would simply push the fire out the window where fire was initially showing on Side A. Why did things turn out so differently than anticipated?

In his analysis of this incident, Captain Hunter points out that there is a considerable difference between a “self-vented” fire and an adequately ventilated fire. As discussed in the April 2008 Officer’s Corner (GFES), horizontally ventilated fires are likely to remain ventilation-controlled. It is important to read the Building, Smoke, Air Track, Heat, and Flame (B-SAHF) indicators to determine the current burning regime (fuel or ventilation-controlled) and anticipate the effect of changes to the ventilation profile.

The fire in the compartment of origin reached flashover resulting in the extension of flames into the center compartment as evidenced by the observation of rollover by the Captain of the engine company performing fire attack. However, the center compartment and the compartment on Side C did not experience flashover (note the condition of contents in the center compartment in Figure 6.). If flashover did not occur in these two compartments, what happened?

In this incident, the fire gases ignited in a flash fire, but combustion did not rapidly transition to a fully developed state in the two compartments adjacent to the compartment of origin.

A flash fire rapidly increases heat release rate, temperature within the compartment and heat flux (as experienced by the fire attack crew in this incident). Like rollover, this phenomenon should not be confused with flashover as fuel in the lower region of the compartment may or may not ignite and sustain combustion. However, fire gas ignition can precede and precipitate flashover (should the fire quickly transition to the fully developed stage).

The concentration of fuel within the hot gas layer varies considerably, with higher concentrations at the ceiling. Concentrations within the flammable range most commonly develop at the interface between the hot gas layer and the cooler air below. Isolated flames (an indicator of a ventilation-controlled fire) are most commonly seen in the lower region of the hot gas layer (as there may be insufficient oxygen concentration in the upper level of the hot gas layer to support flaming combustion). Mixing of the hot gas layer and air due to turbulence increases the likelihood of a significant fire gas ignition.

- What was the ventilation profile and air track when the engine company reached the top of the stairs to begin their attack on the fire?

- How did the tactical ventilation performed from the exterior (removal of the window on floor 2, Side C) influence the ventilation profile and air track?

- What effect do you think that continuous operation of the 30o fog stream had on conditions on floor 2?

- What combination of factors likely resulting in mixing of air and smoke (fuel) leading to the fire gas ignition that drove the fire attack crew off floor 2 and into the stairwell?

Key Considerations and Lessons Learned

This incident points to a number of key considerations and lessons learned.

- Beware the routine incident! Even what appears to be a simple fire in a small residential structure can present significant challenges and threats to your safety.

- Use the B-SAHF indicators to read the fire and consider both the stage of fire development and burning regime (fuel or ventilation-controlled) in strategic and tactical decision making.

- Flame showing is just that. Do not be lulled into a false sense of security by thinking that the fire is adequately ventilated. Read the air track indicators!

- Continue to read the fire after making entry. Smoke is fuel and hot gases overhead are a threat. Observation of isolated flames indicates a ventilation-controlled fire. Rollover often precedes flashover. Take proactive steps to mitigate the threat of extreme fire behavior.

- Recognize that ventilation-controlled fires will increase in heat release rate if additional air is introduced. Manage the ventilation profile using tactical ventilation and tactical anti-ventilation. Anticipate unplanned ventilation due to fire effects.

- Recognize that both horizontal and vertical ventilation are effective when used appropriately and coordinated with fire control. Consider the influence of inlet and exhaust opening location and size when anticipating the influence of tactical ventilation on fire behavior and conditions within the building.

Again special thanks to Captain Shane Hunter and the Omaha Fire Department for sharing the information about this incident and their work to improve firefighter safety.

Ed Hartin, MS, EFO, MIFireE, CFO