Myth of the Self-Vented Fire

Monday, January 26th, 2009When fire is showing from one or more windows or other opening on arrival, firefighters and fire officers often observe that the fire is “self-vented”. While this is true, this unplanned ventilation often increases heat release rate and does not have the desirable effects resulting from effective tactical ventilation.

Effects of Horizontal Ventilation

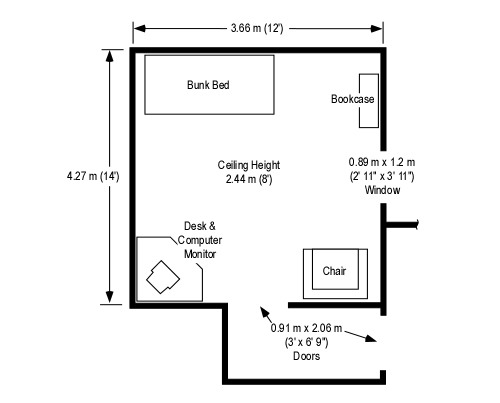

Effect of Positive Pressure ventilation on a Room Fire (Kerber & Walton, 2005) describes a series of experiments performed at the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) to determine the effect of horizontal ventilation using a window and door under natural and positive pressure conditions. These experiments involved a compartment with a single window and doorway as illustrated in Figure 1. The room was furnished as a bedroom with a limited fuel load consisting of a bunk bed, bookcase (without books), chair, and desk with computer monitor.

Figure 1. Horizontal Ventilation Test Floor Plan

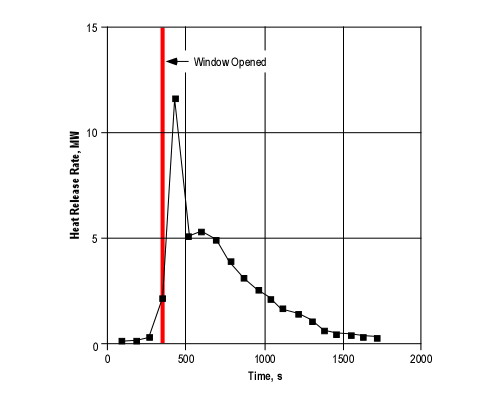

As illustrated in Figure 2, with natural ventilation the heat release rate (HRR) spiked immediately after the window was vented. As heat release rapidly increased, so too did temperature with peak temperature at the ceiling in excess of 1000o C (1832o F).

Figure 2. Heat Release Rate with Natural Horizontal Ventilation

Note: Adapted from Effect of positive pressure ventilation on a room fire, (NISTIR 7213) by S. Kerber & W. Walton

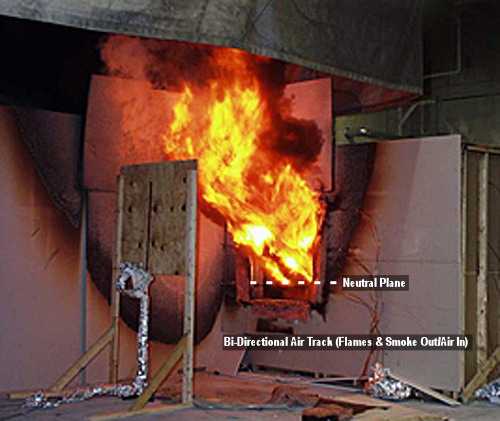

After establishing natural horizontal ventilation by opening the window, a bi-directional air track developed at both the window and door to the compartment as illustrated in Figures 3 and 4. If this compartment was at the end of a long hallway, what impact would the air track and temperature conditions have on firefighters working their way to the seat of the fire?

Figure 3. Air Track at the Door

Figure 4. Air Track at the Window

Click on the link to view video providing interior and exterior views: NIST Natural Horizontal Ventilation Test . Additional information on natural and positive pressure ventilation tests is also available on the NIST PPV web page.

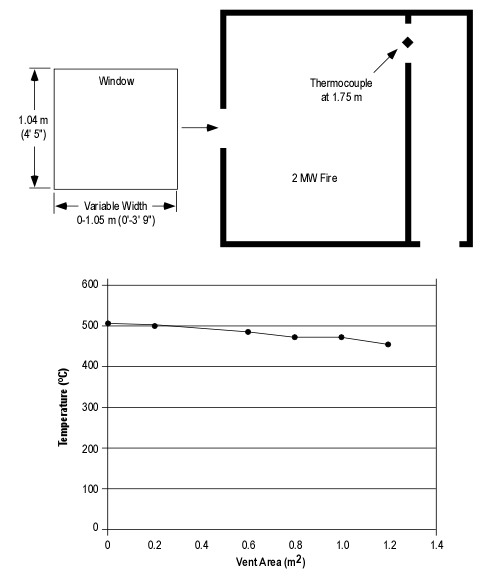

Horizontal ventilation is often performed to lower temperature and raise the level of the hot gas layer in the fire area. While increased ventilation may accomplish this, failure (or tactical ventilation) of a single window is unlikely to have significant impact on compartment temperature.

Researchers from the University of Texas and the Austin Texas Fire Department (Weinschenk., Ofodike,& Nicks, 2008) performed a computer simulation of the impact of variation in the size of the exhaust opening when performing horizontal ventilation using a window and door. The compartment size was slightly smaller than in the NIST study (Kerber & Walton, 2005) and the fire was considerably smaller (2 MW). In this simulation they examined conditions varying from the window being closed to fully open. As illustrated in Figure 5, even with the window fully open, the temperature in the doorway of the compartment dropped only slightly.

Figure 5. Influence of Opening Size on Doorway Temperature

It is essential to recognize that unplanned ventilation caused by failure of window glazing due to the effects of the fire are unlikely to result in sufficient exhaust opening size to have a significant positive influence on conditions inside the fire compartment and adjacent spaces.

What smoke, flame, and air track indicators would point to ventilation controlled conditions? Take a look at Figures 3 and 4! How might tactical anti-ventilation and/or tactical ventilation be used to positively influence fire conditions and the environment in the compartment?

So What?

Horizontal ventilation is an excellent tool when used correctly. However, not understanding the influence of changes to the ventilation profile when the fire is ventilation controlled, can have disastrous consequences. Ventilation direction (horizontal or vertical), size and location of inlet and exhaust openings, and coordination with fire control are critical to safe and effective fireground operations.

References

For more information, see the following NIST report and journal article.

Kerber, S. & Walton, W. (2005). Effect of positive pressure ventilation on a room fire, (NISTIR 7213). Retrieved January 26, 2009 from http://fire.nist.gov/bfrlpubs/fire05/PDF/f05018.pdf

Weinschenk, C., Ofodike, E., & Nicks, R. (2008) Analysis of fireground standard operating guidelines/procedures for compliance for Austin fire department. Fire Technology, 44(1), 39-64.

Remember the Past

I am involved in an ongoing project to assemble and examine narratives, incident reports, and investigations related to extreme fire behavior events. Unfortunately many of these documents relate to line of duty deaths. As I read through the narratives included in the United States Fire Administration line of duty death database and annual reports on firefighter fatalities, I realized that every week represents the anniversary of the death of one or more firefighters as a result of extreme fire behavior.

While some firefighters have heard about the incidents involving multiple fatalities, others have not and most do not know the stories of firefighters who died alone. In an effort to encourage us to remember the lessons of the past and continue our study of fire behavior, I will occasionally be including brief narratives and links to NIOSH Death in the Line of Duty reports and other documentation in my posts.

January 28, 1994

Firefighter Vencent Acey, 42, Career

Firefighter John Redmond, 41, Career

Philadelphia Fire Department, Pennsylvania

On January 28, Firefighters Vencent Acey and John Redmond, both of the Philadelphia (PA) Fire Department, died when he became trapped and overcome by smoke by a rapidly moving fire in the basement of a church. Several firefighters re-entered the church against orders to rescue the firefighters, and were able to pull one of them from the basement. Eight other firefighters were injured, including several involved in the rescue efforts.

January 28, 1995

Firefighter Victor Melendy, 47, Career

Stoughton Fire Department, Massachusetts

On January 28, Firefighter Victor Melendy of the Stoughton (MA) Fire Department died when he was caught in a flashover while searching for victims on the third floor of a rooming house.

January 27, 2000

Captain Walter Harvey Gass, 74, Volunteer

Sealy Volunteer Fire Department, Texas

Captain Gass and other members of his department were dispatched to a residential structure fire that was caused when lightning struck a house. The first two firefighters on the scene, the Assistant Chief and the Fire Chief, confirmed a working fire with dark smoke and fire visible from the attic and dormers. Captain Gass and his crew were the first fire company to arrive at the scene. Captain Gass and two firefighters entered the structure through the front door to perform an aggressive attack on the fire. Shortly after entering the structure, the two firefighters who were with Captain Gass were attempting to feed more hose into the structure. There was a rapid buildup of heat and the hoseline seemed to drop. The firefighters exited the building and reported this situation to the Chief. Two Rapid Intervention Teams (RIT) were formed and, after four attempts, the second team was successful in recovering Captain Gass. Captain Gass was equipped with full structural protective clothing and a manually activated PASS device. The PASS was found in the “off” position. Captain Gass was located about 18 feet inside the front door of the structure. Captain Gass was removed from the structure approximately 20 minutes after his arrival on the scene. The cause of death was listed as smoke and soot inhalation with greater than 80 percent total thermal injury. Additional information about this incident may be found in NIOSH Fire Fighter Fatality Investigation F2000-09.

Seeking Information

If your department experiences (or has experienced) an extreme fire behavior event and you would be willing to share information about the incident or lessons learned, please contact me by e-mail or telephone.