Live Fire Training Part 2:

Remember Rachael Wilson

Thursday, February 19th, 2009

25 Years Later

Firefighters Scott Smith and William Duran died as a result of flashover during a search and rescue drill in Boulder, Colorado on January 26, 1982 (Demers Associates, 1982, August). This incident has particular significance in that it was one of the major influences in the development of National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) Standard 1403 Live Fire Training Evolutions in Structures (NFPA, 1986). 25 years after the deaths of the two firefighters in Boulder, rapid fire progress during live fire training claimed the life of Firefighter Paramedic Apprentice Rachael Wilson in Baltimore, Maryland (Shimer, 2007; NIOSH, 2008)

What makes this even more tragic is that unlike the incident in Boulder, for the last 20 years the fire service has had a national consensus standard that defines minimum acceptable practice for live fire training.

Training Exercise on South Calverton Road

Information on the incident that resulted in the death of Firefighter Paramedic Apprentice Rachael Wilson was drawn from the Independent Investigation Report: Baltimore City Fire Department Live Fire Training Exercise 145 South Calverton Road February 9, 2007 (Shimer, 2007) and NIOSH Death in the Line of Duty Report F2007-09 (NIOSH, 2008).

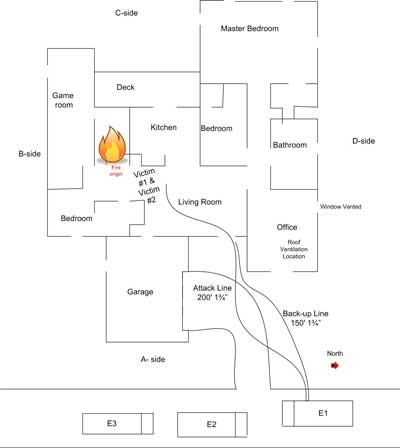

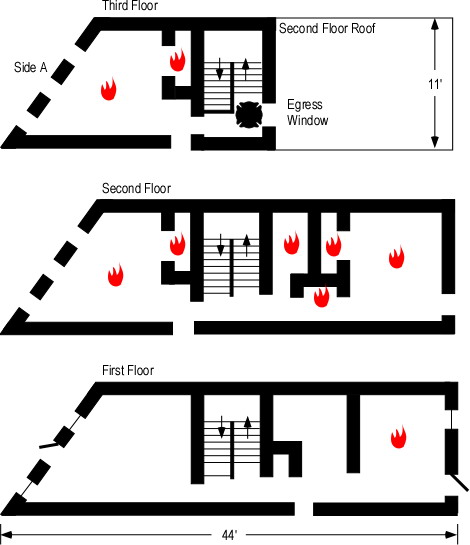

On February 9, 2007 twenty-two members of Baltimore City Fire Department Firefighter Paramedic Apprentice Class 19 were participating in live fire training in an acquired structure. The objectives of this training exercise included practice in fire attack, primary search, forcible entry, and ventilation. The building used for this training exercise was a three story, single family row house of ordinary (masonry and wood joist) construction. The building was of somewhat unusual design with the front (A Side) of the building constructed at an angle (parallel to the street) resulting in a trapezoidal floor plan as illustrated in Figure 1. The third floor was considerably smaller than the first two floors with third floor windows on Side C looking out over the second floor roof. The building had previously been used for training and ceilings and portions of the walls on the second and third floors had been opened up during ventilation and forcible entry practice.

Five instructors assigned to the Training Academy and six adjunct instructors were responsible for managing the live fire training exercise and providing instruction. Lieutenant Crest (Training Academy staff) served as Incident Commander and Division Chief Hyde served as the Safety Officer. Two instructors were assigned as the ignition team and others were assigned to supervise assigned crews of Firefighter Paramedic Apprentices. An engine and truck from the Training Academy were positioned on the A Side of the building. The engine was supplied by a hydrant through a single large diameter hoseline.

The plan for the training exercise called for eight separate fuel packages on Floors 2 (two fuel packages) and 3 (six fuel packages) to be ignited. Each fuel package consisted of one or three pallets and excelsior (soft shredded wood packing material). Crews would be assigned to fire attack on floors two and three while other crews performed forcible entry (in support of fire attack) primary search, ventilation. The trainees were divided into five companies, designated Engine 1 (fire attack on Floor 3), Engine 2 (fire attack on Floor 2), Truck 1 (placement of ladders and then search and rescue), Truck 2 (assist with forcible entry on Side C), and Truck 3 (vertical ventilation). While the Incident Commander outlined the plan for the instructors, the trainees were not provided with a walkthrough of the building or safety briefing prior to the start of the live fire exercise.

The Incident Commander (Lieutenant Crest) accompanied the ignition team into the building and supervised ignition of the fires on Floors 3 and 2. While none of the instructors indicated doing so, a fire was also lit in debris (three mattresses, automobile tire, upholstered chair, and other combustible materials) located just inside the doorway on Floor 1 Side C.

Fire Attack

The crew designated Engine 1 consisted of Emergency Vehicle Driver Wenger (Instructor) and Firefighter Paramedic Apprentice Wilson (nozzle), Paramedic Cisneros (2nd on the line), and Firefighter Paramedic Apprentices Perez, and Lichtenberg. Engine 1 was tasked with fire attack on Floor 3. None of the crew from Engine 1 was equipped with a portable radio and received their orders face-to-face from Command. When the instructor questioned passing the fire on Floor 2, Command indicated that another line would be coming in right behind them and to go directly to Floor 3. Engine 1 entered from Side A with a 1-3/4″ (45 mm) hoseline and proceeded up the interior stairwell. None of the members of this crew indicated seeing fire on Floor 1 at the time they made entry.

Figure 1. Baltimore Floor Plan.

Note: Adapted from City of Baltimore. Independent investigation report: The Baltimore city fire department live fire training exercise 145 South Calverton Road February 9, 2007, (Shimmer, 2007, pp. 13)

Upon reaching Floor 2, Engine 1 encountered severe fire conditions and the instructor did not feel comfortable proceeding to Floor 3 without controlling the fire on Floor 2. He instructed Apprentice Wilson to open the nozzle and put water on the fire. In the process of doing so, she fell and the instructor took over the nozzle. He (the instructor) knocked the fire down to the point where he felt that his crew could advance to Floor 3 (bud did not completely control or extinguish the fire on Floor 2). At this point he returned the nozzle to Wilson. Wilson and Cisneros and the instructor proceeded to Floor 3 while Perez, and Lichtenberg remained in the stairwell pulling hose.

Trapped Above the Fire

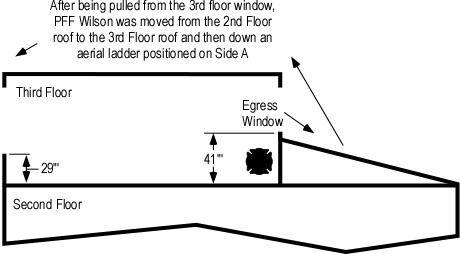

After reaching Floor 3, Cisneros (2nd on the line behind Wilson) advised the instructor that Floor 2 was well involved. He instructed her to go into the stairwell and pull up additional hose. She felt intense heat on her legs and advised the instructor that she needed to get out of the building. The instructor climbed through the egress window (see Figure 2) and assisted Cisneros out the window and onto the second floor roof. At this point, Wilson was maintaining a position at the egress window (located at the top of the stairwell) with the nozzle.

Figure 2. Baltimore Cross Section of Floor 3

Note: Adapted from City of Baltimore. Independent investigation report: The Baltimore city fire department live fire training exercise 145 South Calverton Road February 9, 2007, (Shimmer, 2007, pp. 13 & 21-27)

While Engine 1 was making their way to Floor 3, Engine 2 entered from Side C with a 1-3/4″ (45 mm) hoseline, intending to proceeding to Floor 2 as ordered, but encountered a significant fire on Floor 1 with flames beginning to roll across the ceiling. Engine 2 attacked the fire on Floor 1 (which delayed their advancement to Floor 2).

Perez and Lichtenberg (members of Engine 1’s crew pulling hose in the stairwell) felt a rush of air followed by flames rapidly extending up the stairwell from Floor 2 to Floor 3. They moved to the top of the stairs and observed Wilson trying to climb through the egress window. Wilson warned them to get out of the building. Heeding her warning, they proceeded down the stairway with the hoseline and controlled the fire on Floor 2 sufficiently to permit them to exit the building, meeting the crew of Engine 2 who were making their way to Floor 2.

Wilson advised Wenger (instructor with Engine 1) that she needed to get out. She had dropped the nozzle (still operating) and was trying to climb out the window. Wenger tried unsuccessfully to pull her out the window (note the height of the window sill in Figure 2). Wenger asked Wilson if she could help him get her out the window. She replied that she could not and that she was burning up. Wenger lost his grip on Wilson and she fell back into the building. Regaining his grip he pulled her partially out the window again, noticing that her breathing apparatus facepiece was partially displaced. Wenger called for help (shouting as he had no radio). Three members of Truck 3 who were working on the third floor roof dropped down to the second floor roof to assist, but were unable to pull Wilson from the window.

Emergency Vehicle Driver Hiebler (instructor with Engine 2) heard a commotion on Floor 3. He ordered one of his crew to accompany him to Floor 3 with the hoseline and the others to remain in place on Floor 2. Reaching Floor 3, they observed Wilson at the window and Wenger (instructor from Engine 1) working from the second floor roof trying unsuccessfully to pull her out the window. Concerned about the fire on Floor 3, Hiebler instructed the trainee to extinguish the fire while he assisted in getting Wilson out the window.

Wilson was unconscious, pulseless and apnic when she was removed from Floor 3. Her breathing apparatus and protective clothing was removed and cardio pulmonary resuscitation (CPR) was initiated while she was on the second floor roof. At the Incident Commander’s direction she was moved up to the third floor roof so that she could be brought down an aerial ladder that had been placed to the roof from Side A. Prior to being brought down from the third floor roof, Wilson was packaged on a backboard and placed in a stokes basket. On reaching the ground advanced life support medical care was initiated and Wilson was transported to the local trauma center where she was pronounced dead. Firefighter Paramedic Apprentice Rachael Wilson died as a result of thermal injuries and asphyxia.

The Aftermath

The initial investigation of this incident was conducted by the Baltimore City Fire Department, Baltimore City Police Department Arson Unit, and United States Bureau of Alcohol Tobacco and Firearms. Subsequently, Mayor Sheila Dixon commissioned an independent investigation into the circumstances surrounding the death of Rachael Wilson lead by Deputy Chief Chris Shimer of the Howard County Department of Fire and Rescue Services. This investigation concluded that there were in excess of 50 deviations from accepted practice as defined by National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) 1403 Standard on Live Fire Training Evolutions (2002). In addition, the investigators identified significant issues related to the organizational culture of the Baltimore City Fire Department that resulted in a lack of accountability compliance with accepted safety practices (Shimer, 2007)

The Maryland Department of Labor, Licensing, and Regulation cited the Baltimore City Fire Department for 33 safety violations and singled out the fire officers who served as Incident Commander and Safety Officer for the haphazard planning and execution of this live fire training exercise (Linskey, 2007a)

The Baltimore City Fire Department fired Training Division Chief Kenneth Hyde who was the Safety Officer and senior fire officer present at the fatal incident. Citing negligence and incompetence in their roles as Incident Commander (Crest) and supervisor of the rapid intervention team (Broyles) during this incident (Linskey, 2007b) Lieutenants Joseph Crest and Barry Broyles were also terminated.

Following votes of no confidence from the Baltimore City Firefighters and Fire Officers unions and continuing criticism, Fire Chief William Goodwin resigned in November 2007, ten months after the death of Firefighter Paramedic Apprentice Rachael Wilson (Fritze & Reddy, 2007)

Now What?

Rachael Wilson’s death was the result of a complex web of contributing factors. It is easy to say that failure to comply with the provisions of standards and regulations regarding live fire training was the problem. But it is more complex than that. It is essential that we examine our organizational culture and training practices on an ongoing basis and ask hard questions regarding the safety and effectiveness of what we do.

Ed Hartin, MS, EFO, MIFireE, CFO

References

Demers Associates. (1982, August) Two die in smoke training drill. Fire Service Today, 17-63.

Fritze, J. & Reddy, S. (2007) City’s fire chief resigns. Retrived June 5, 2008 from http://baltimoresun.com/recruit

Linsky, A. (2007c) Baltimore fire department cited in cadet’s death. Retrieved June 4, 2008 from http://baltimoresun.com/recruit

Linsky, A. (2007d) City dismisses two more fire officials. Retrieved June 4, 2008 from http://baltimoresun.com/recruit

National Fire Protection Association. (1986). Standard on live fire training evolutions in structures. Quincy, MA: Author.

National Fire Protection Association. (2002). Standard on live fire training. Quincy, MA: Author.

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). (2002). Death in the line of duty, F2007-09. Retrieved February 19, 2009 from http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/fire/pdfs/face200709.pdf

Shimer, R. (2007) Independent investigation report: Baltimore city fire department live fire training exercise 145 South Calverton Road February 9, 2007. Retrieved February 19, 2009 from http://www.firefighterclosecalls.com/pdf/BaltimoreTrainingLODDFinalReport82307.pdf.