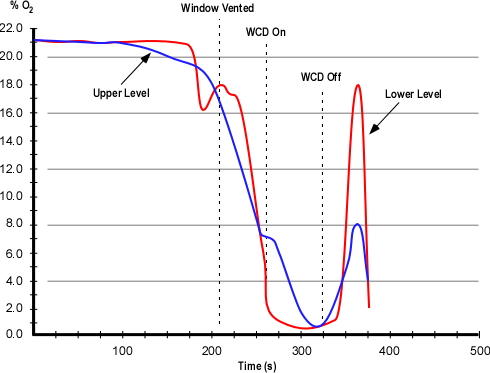

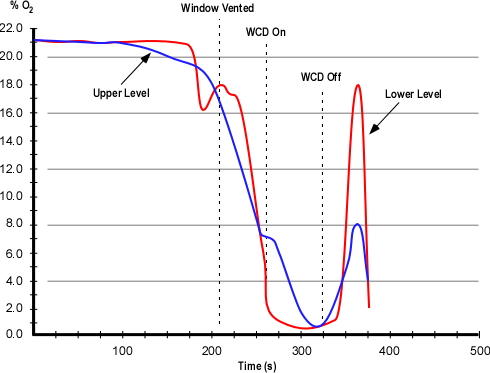

My last post examined National Institute for Standards and Technology (NIST) tests of wind control devices to mitigate hazards presented during wind driven compartment fires (Fire Fighting Tactics Under Wind Driven Conditions). Heat release rate (HRR) data from Experiment 1 (baseline test with no wind) and Experiment 3 (wind driven) illustrates the dramatic influence of increasing ventilation to a ventilation controlled fire and even more dramatic impact when increased ventilation is coupled with wind (see Figure 1). This post posed several questions related to the HRR data from these experiments.

Figure 1. Heat Release Rates in Experiments 1 (Baseline) and 3 (Wind Driven)

Note: Adapted from Firefighting Tactics Under Wind Driven Conditions.

Note: Adapted from Firefighting Tactics Under Wind Driven Conditions.

Questions

Examine the HRR curves in Figure 1 and answer the following questions:

- What effect did deployment of the wind control device have on HRR and why did this change occur so quickly?

- How did HRR change when the wind control device was removed and why was this change different from when the window was vented?

- What factors might influence the extent to which HRR changes when ventilation is increased to a compartment fire in a ventilation controlled burning regime?

Answers: Application of the wind control device rapidly decreased heat release rate from approximately 19 MW to 5 MW. With the window covered, the fire lacked sufficient oxygen to maintain the higher rate of HRR. As oxygen was quickly consumed (and oxygen concentration was decreased) by the large volume of flaming combustion in the compartments, heat release rate was rapidly reduced.

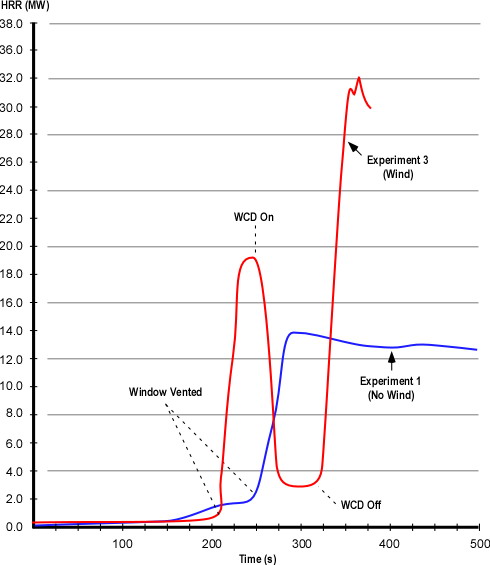

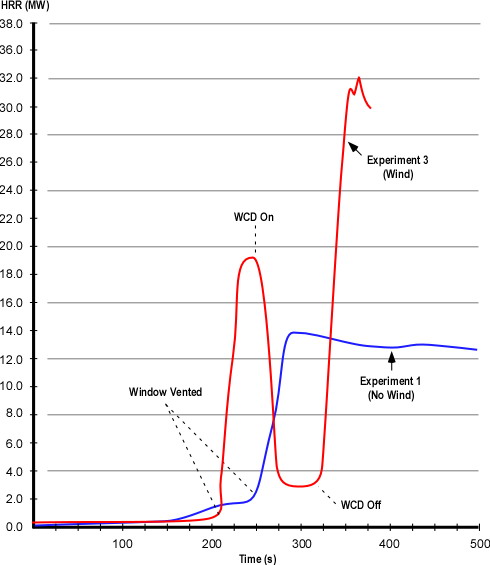

As with the change in HRR when the window was vented, removal of the wind control device resulted in an extremely rapid increase in HRR as additional oxygen was provided to the ventilation controlled fire inside the structure. In this case, the increase was even more significant with the peak HRR reaching approximately 32 MW. Examination of the oxygen concentration curve provides a hint of why this might have been the case (see Figure 2). The oxygen concentration was higher before the window was vented than when the wind control device was removed. The more rapid and greater rise in HRR is likely a result of the extent to which the fire was ventilation controlled and the available concentration of gas phase fuel. After the wind control device was removed, note that the oxygen concentration increased sharply (which relates to the rapid increase in HRR), followed by a rapid decrease as ventilation was inadequate to maintain that rate of combustion.

Figure 2. Oxygen Concentration in the Bedroom

Note: Adapted from Firefighting Tactics Under Wind Driven Conditions.

Practical Application

The results of the NIST research are extremely interesting to students of fire behavior. However, it is essential that we be able to transform this information into knowledge that has practical application. This gives rise to three fundamental questions:

- How do changes in ventilation influence fire behavior? Note that this is always a concern, not just under wind conditions!

- What impact will wind have if the ventilation profile changes?

- What tactical options will be effective in mitigating hazards presented by extreme fire behavior under wind driven conditions?

It is important to consider air track and the flow path from inlet to exhaust opening and the potential consequences of introducing air under pressure without (or with an inadequate) exhaust opening. Both can have severe consequences!

Tactical Problem

One good way to wrestle with the influence of wind on compartment fire behavior is to put it into a realistic context. In the following tactical problem you will be presented with an incident scenario and a series of questions. Apply what you have learned and consider how you would approach this incident.

Resources: You have what you have! Use your normal apparatus assignment and staffing levels when working through this tactical problem.

Weather Information: Conditions are clear with a temperature of 20o C (68o F) and a 24 kph (15 mph) wind out of the Northwest.

Dispatch Information: You have been dispatched to a residential fire at 0700 on a Sunday morning. The caller reported seeing smoke from a house at 1237 Lakeview Drive. After companies go enroute, the dispatcher provides an update that she is receiving multiple calls for a fire at this location.

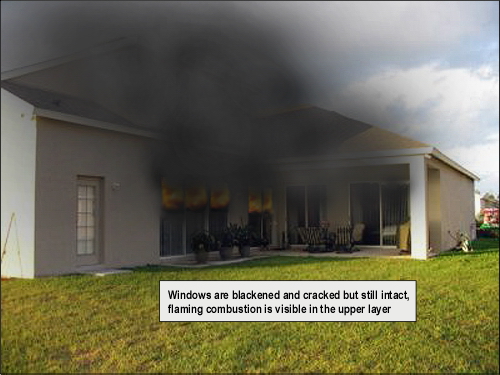

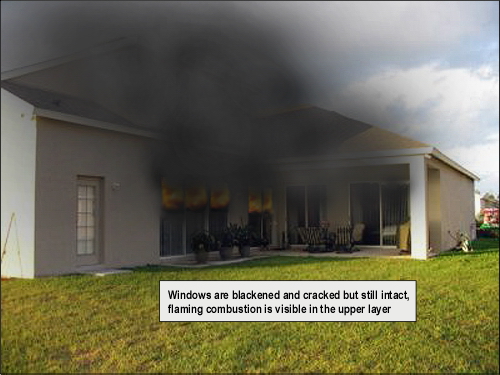

Conditions on Arrival: Approaching the incident location you observe a moderate volume of medium gray smoke from a wood frame, single family dwelling (most structures in this area are of lightweight construction). Smoke is blowing towards the A/D corner of the structure. As illustrated in Figure 3, smoke is visible from the front entry (window and door) of the house and it appears that smoke is showing from Side C as well. On closer examination, you observe that the upper level of the windows on Side A are stained with condensed pyrolysis products, but are intact.

Figure 3. View from Side A

360o Reconnaissance: Moving down Side B, you observe a substantial body of fire in the center of the house. Smoke is pushing from around several sliding glass doors on Side B (see Figure 4) and flames are visible in the upper layer. The glass in the sliding doors is blackened and cracked, but is still intact. Smoke is also visible from around a large window on Side B Floor 2. Smoke discharge on Side B is swirling and being pushed up over the roof by the wind.

Figure 4. View from the BC Corner

Proceeding around the structure to Sides C and D, you observe a small amount of smoke pushing out from around the windows on Side D.

Questions: The first set of questions deals with size-up and development of an initial plan of action.

- What B-SAHF indicators do you observe in Figures 2 and 3?

- What stage(s) of fire development is (are) likely to exist in the structure?

- What burning regime is the fire in?

- How is the fire likely to develop in the time that it will take to develop and implement your incident action plan?

- Would you have given orders to your crew (or would they have taken pre-planned standard actions) based on your observation of conditions on Side A (Figure 1)? If so what would have been done? Why?

- Would your action plan have changed based on your observations from the B/C corner? What would you do differently? Why?

- What is your action plan at this point? Do you have sufficient resources? What orders would you give the first alarm companies? What actions would you have your crew take? Why?

Your action plan is dependent on size-up and assessment of incident conditions. Variation in conditions may result in a change in the priority or sequence of tactical action. Would your action plan have been different if the dispatcher had indicated that the caller was trapped in the house? If it would have, what would you have done differently? Why?

Things to Think About

This tactical problem presents a number of challenges. Click on the link to examine the Floor Plan and then consider the following questions:

- What conditions would firefighters have encountered if they made entry through the door on Side A (front door)? Why?

- How would these conditions have changed if glass in one or more of the sliding doors on Side B had failed after firefighters had made entry? Why?

- What conditions would have resulted if the glass in one or more of the sliding doors on Side B had failed and the door on Side A was not open? Why?

- What options for fire attack and tactical ventilation would have been effective in this situation? Would your choice fire attack and tactical ventilation location, sequence, and coordination have varied based on the report of occupants? Why?

- How did your knowledge of the results of the NIST tests on wind driven fires impact your understanding of this incident? How did this understanding influence your tactical decision-making?

It is important to practice strategic and tactical decision-making. However, it is also important to think about how and why we make these decisions. This meta-learning (learning about our learning) has a significant impact on our professional development and ability to learn our craft.

Remember the Past

As discussed in previous posts, it is important to honor the sacrifices of firefighters who have died in the line of duty and not lose lessons learned as time passes. The following narratives were taken from the United States Fire Administration (USFA) reports on Firefighter Line of Duty Deaths (1994 and 2004).

March 29, 1994

Captain John Drennan, 49, Career

Firefighter James Young, 31, Career

Firefighter Christopher Seidenburg, 25, Career

Fire Department of the City of New York, New York

On March 29, three firefighters trapped in the stairwell of a brownstone were burned when they were enveloped in fire while attempting to force their way through a heavy steel door to a second floor apartment. Captain John Drennan, Firefighter James Young, and Firefighter Christopher Seidenburg of the New York City Fire Department were conducting a search when the hot air and toxic gases that collected in the stairwell erupted into flames as other fire crews forced entry into the first floor apartment where the fire had originated. The fire exhibited characteristics of both a backdraft and a flashover. Firefighter Young, in the bottom position on the stairs, was burned and died at the scene. Firefighter Seidenberg and Captain Drennan were rescued by other firefighters. They were transported to a burn unit with third and fourth degree burns over 50 of their bodies. Seidenburg died the next day. Drennan passed away several weeks later. The fire cause was determined to be a plastic bag left by the residents on top of the stove of the floor apartment.

For additional information on this incident see:

Bukowski, R. (1996). Modeling a backdraft: The 62 Watts Street incident. Retrieved March 14, 2009 from http://fire.nist.gov/bfrlpubs/fire96/PDF/f96024.pdf

March 21, 2003 – 0850

Firefighter Oscar “Ozzie” Armstrong, III, Age 25, Career

Cincinnati Fire Department, Ohio

Firefighter Armstrong and the members of his fire company responded to the report of a fire in a two-story residence. The first fire department unit on the scene, a command officer, reported a working fire.

Firefighter Armstrong assisted with the deployment of a 350-foot, 1-3/4-inch handline to the front door of the residence. Once the door was forced open, firefighters advanced to the interior. The handline was dry as firefighters advanced; the hose had become tangled in a bush.

As the line was straightened and water began to flow to the nozzle, a flashover occurred. The firefighters on the handline left the building and were assisted by other firefighters on the front porch of the residence. All firefighters were ordered from the building, air horns were sounded to signal a move from offensive to defensive operations.

Several firefighters saw Firefighter Armstrong trapped in the interior by rapid fire progress. These firefighters advanced handlines to the interior and removed Firefighter Armstrong. A rapid intervention team assisted with the rescue.

Firefighter Armstrong was severely burned. He was transported by fire department ambulance to the hospital where he later died.

The origin of the fire was determined to be a pan of oil on the stove.

For additional information on this incident see:

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). (2005). Death in the line of duty report F2003-12. Retrieved March 14, 2009 from http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/fire/pdfs/face200312.pdf

Laidlaw Investigation Committee. (2004)Line of duty death enhanced report Oscar Armstrong III March 21, 2004. Retrieved March 14, 2009 from http://www.iafflocal48.org/pdfs/enhancedloddfinal.pdf

Ed Hartin, MS, EFO, MIFireE, CFO

References

Madrzykowski, D. & Kerber, S. (2009). Fire fighting tactics under wind driven conditions. Retrieved (in four parts) February 28, 2009 from http://www.nfpa.org/assets/files//PDF/Research/Wind_Driven_Report_Part1.pdf; http://www.nfpa.org/assets/files//PDF/Research/Wind_Driven_Report_Part2.pdf;http://www.nfpa.org/assets/files//PDF/Research/Wind_Driven_Report_Part3.pdf;http://www.nfpa.org/assets/files//PDF/Research/Wind_Driven_Report_Part4.pdf.

United States Fire Administration (USFA). (1995) Analysis report on firefighter fatalities in the United States in 1994. Retrieved March 14, 2009 from http://www.usfa.dhs.gov/downloads/pdf/publications/ff_fat94.pdf

United States Fire Administration (USFA). (2005). Frefighter fatalities in the United States in 2004. Retrieved March 14, 2009 from http://www.usfa.dhs.gov/downloads/pdf/publications/fa-299.pdf

Note: Adapted from Firefighting Tactics Under Wind Driven Conditions.

Note: Adapted from Firefighting Tactics Under Wind Driven Conditions.