Basic Nozzle Techniques and Hose Handling

Monday, November 2nd, 2009The previous post in this series, My Nozzle, examined the importance of nozzle knowledge and skill in using the firefighter’s primary weapon in offensive firefighting operations.

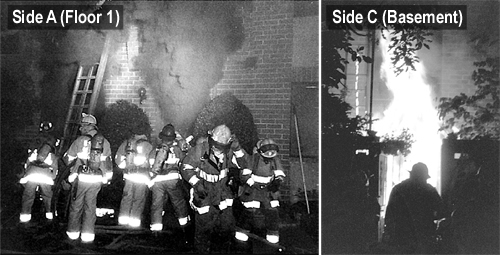

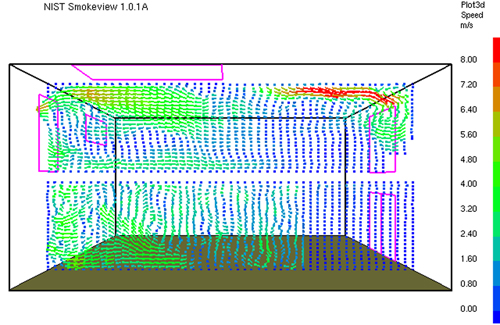

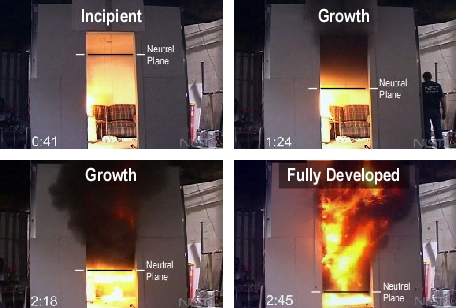

Figure 1. Practice is Essential to Effective Nozzle Technique

Note: These Fire Officers from Rijeka, Croatia are practicing the short pulse to place water fog into the hot gas layer. Droplet size, cone angle, position of the nozzle, and duration of application have placed water in the right form exactly where it was intended.

This is my nozzle, there are many like it but this one is mine. My nozzle is my best friend. It is my life. I must master it as I master my life. Without me it is useless, without my nozzle I am useless.

I will use my nozzle effectively and efficiently to put water where it is needed. I will learn its weaknesses, its strengths, its parts, and its care. I will guard it against damage, keep it clean and ready. This I swear [adapted from the Riflemans Creed, United States Marine Corps].

This post continues with a discussion of training methods and techniques that can be used to develop proficiency in nozzle techniques and hose handling.

Limitations in Fire Service Instructional Methods

Fire service instructor training and related instructional methods have direct linkage to the philosophy of vocational education that evolved in the United States in the early 1900s (Hartin, 2004). The philosophy of vocational education that evolved in the first half of the 20th century put forth a mechanistic view of training and vocational education in which the goal is efficient production of trained individuals (Allen, 1919; Prosser & Allen, 1925). In early fire service instructor training, basic concepts of vocational education were combined with behaviorist psychological concepts of positive and negative reinforcement to guide learning. Over the last four decades, fire service instructor training has evolved to include humanist perspectives on motivation and the characteristics of adult learners. However, the basic principles used in training factory workers to perform simple repetitive tasks remain the meat and potatoes of this theoretical stew. All very interesting, but what does this have to do with nozzle technique?

The dominant focus of most fire service instructor training programs is on classroom instruction and to a lesser extent on demonstration of basic skills as an instructional method. Less focus is placed on effective methods for skills instruction (other than demonstration) and more importantly how to coach and provide effective feedback during skills instruction. Effectively and efficiently developing firefighters’ psychomotor skills requires a somewhat different focus.

There is a commonality between firefighters and athletes. Both require development of a wide range of physical and mental skills as well as underlying knowledge. A tremendous amount of research has been conducted on effective approaches to development of skill and proficiency in sport. Kinesiology (the science of human movement) and sport psychology provide a useful starting point for improving fire service skills training. While this post is focused on nozzle techniques and hose handling, the underlying theories can be applied to many other skills. It is essential that both the coach and the learner not only understand what needs to be done and how to do it, but why!

Motor Learning and Performance

A motor skill can be conceptualized as a physical task such as operating a nozzle or stretching a charged hoseline through a building. However, there are a number of dimensions on which these types of task can be classified:

- Task organization (simple, single task or multiple, interconnected tasks)

- Importance of motor and cognitive elements (doing or thinking)

- Environmental predictability (consistent or variable conditions)

Simply opening and closing the nozzle is a discrete task that predominantly involves motor skill, and takes place in a fairly predictable environment (the firefighters’ position may change, but the nozzle remains the same). However, when placed in the context of hoseline deployment inside a structure with variable fire conditions things change quite a bit. This involves serial (multiple, sequential) tasks and requires both physical and cognitive (decision-making) skills, in a somewhat predictable, but highly variable environment. This explanation makes things seem a bit more complicated than they appear at first glance!

Motor learning can be divided into several relatively distinct stages (Schmidt & Wrisberg, 2008). In the verbal-cognitive stage, learners are dealing with an unfamiliar task and spend time talking and thinking their way through what they are trying to do. As learners progress to the motor stage, they have a general idea of the movement required and shift focus to refining their skill. Progression through the motor stage often requires considerable time and practice. Some learners progress to the autonomous stage in which action is produced almost automatically with little or no attention. Other than the newest recruits, most firefighters are in the motor stage of learning when developing skill in nozzle techniques and hose handling.

Developing an understanding of motor performance and learning requires a conceptual model. However, in that many of you are likely to be less excited about learning theory than I am, I will make an effort to limit this to a simple framework.

- Stimulus Identification: Recognize the need for physical action

- Response Selection: Determination of the action needed.

- Response Programming: Preparation and initiation of the required action.

- Feedback: Determination of the effectiveness of the action (this loops back to stimulus identification and the process begins again).

In some cases, feedback is obtained during the action and corrective action can be taken during task performance (closed loop control). In other (shorter duration) tasks, feedback is received after the task is completed (open loop control)

Many nozzle techniques such as application of a short pulse of water fog into the hot gas layer involve open loop control as the action is completed before the firefighter can receive and process feedback on the effectiveness of the action. Training must develop sufficient skill (and preferably automaticity) to allow firefighters to apply various nozzle techniques with minimal conscious thought to allow focus on maintaining orientation in the building and key fire behavior indicators.

While there is much more to the story, this limited explanation of motor learning and performance provides a starting point to understand why the nozzle technique and hose handling drills are important and why they are designed the way that they are.

Nozzle Technique and Hose Handling Drills

One more bit of learning theory before we get our hands on the nozzle. This sequence of drills is designed using the Simplifying Conditions Method (Reigeluth, 1999). This approach moves from simple to complex, beginning with the simplest version of the task that represents the whole and moves to progressively more complex versions until the desired level of complexity is reached. In the case of nozzle technique and hose handling, this involves moving from basic, individual skills, to team skills, and on to integration of physical skills and decision-making.

Once basic proficiency is developed in simple tasks (such as the short pulse, long pulse, penciling, and painting), practice should be randomly sequenced (rather than blocked into practice of a single skill). In addition, practice should be distributed over a number of shorter sessions, rather than massed into fewer, but longer sessions. For more information on design of effective and efficient practice sessions, see Motor Learning and Performance (Schmidt & Wrisberg, 2008).

Drill 1-Basic Skills in Nozzle Operation: The starting point in developing a high level of proficiency in nozzle use is to gain familiarity with the nozzle(s) you will be using including performance characteristics such as flow rate, operating pressure, and nozzle controls (i.e., shutoff, pattern, flow). In addition, firefighters should build skill in basic nozzle techniques such as the short pulse, long pulse, penciling, and painting while in a fixed position. Click on the following link to download the instructional plan for Drill 1 in PDF format.

Hose and Nozzle Technique Drill 1 Instructional Plan

Firefighting is team based. After firefighters have demonstrated individual proficiency in basic nozzle techniques from a fixed position, the next step is to apply these techniques in a team context.

Drill 2-Hose Handling and Nozzle Operation: Firefighters often lose focus on nozzle technique and operation when they are moving. This drill provides an opportunity for the firefighter with the nozzle and backup firefighter to develop a coordinated approach to movement and operation.

Drill 3-Nozzle Operation Inside Compartments: Deployment of hoselines inside a building requires a somewhat different set of skills than simply moving forward and backward. Movement of hoselines around corners and adjustment of nozzle pattern to cool gases in hallways and varied size compartments are important additions to the firefighters’ skill set and provide the next step in developing proficiency in nozzle use.

Drills 2 and 3 will be addressed in the next post in this series. Subsequent posts will address door entry procedures, indirect attack, and will introduce the concept of battle drills to build skill in dealing with worsening conditions or other emergencies while operating inside burning buildings.

Ed Hartin, MS, EFO, MIFIreE, CFO

References

Hartin, E. (2004). Theoretical foundations of fire service instructor training (unpublished manuscript available from the author). Portland State University.

Allen, C. R. (1919). The instructor the man and the job. Philadelphia, PA: J. B. Lippencott Company. Prosser, C. A., & Allen, C. R. (1925). Vocational education in a democracy. New York: The Century Company.

Schmidt, R. & Wrisberg, C. (2008). Motor learning and performance (4th ed.). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

Reigeluth, C. (1999). Elaboration theory: Guidance for scope and sequence decisions. In C.M. Reigeluth (Ed.) Instructional-design theories and models: A new paradigm of instructional theory volume II. Mawah, NH: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.