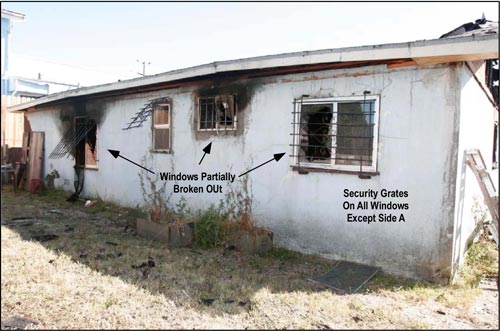

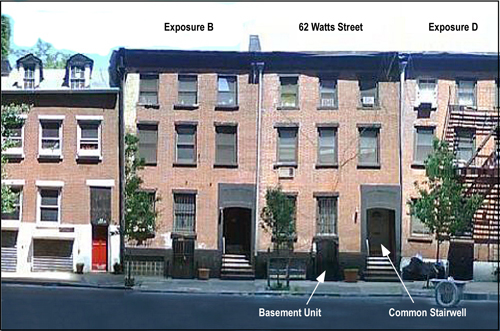

This post continues examination of the incident that took the lives of Captain Matthew Burton and Engineer Scott Desmond early on the morning of July 21, 2007. Captain Burton and Engineer Desmond died while conducting primary search in a small, one-story, wood frame dwelling with an attached garage at 149 Michele Drive in San Pablo (Contra Costa County), California.

This post focuses on firefighting operations, key fire behavior indicators, and firefighter rescue operations implemented after Captain Burton and Engineer Desmond were discovered after rapid fire progression in the area in which they were searching.

Firefighting Operations

Based on the report of trapped occupants, E70 immediately placed a 150′ preconnected 1-3/4″ (45 m 45 mm) line into service using apparatus tank water. The officer of E70, seeing what he believed to be E74 arriving he passed command to the E74 officer. Unfortunately, the second arriving engine was E73 (using apparatus normally assigned to Station 74 and marked E74).

Note: This incomplete passing of command resulted in loss of command, control, and coordination of tactical operations until the arrival of BC7 at 0202 and formally assumed command at 0205. All tactical operations prior to 0205 were the result of independent action by first alarm companies.

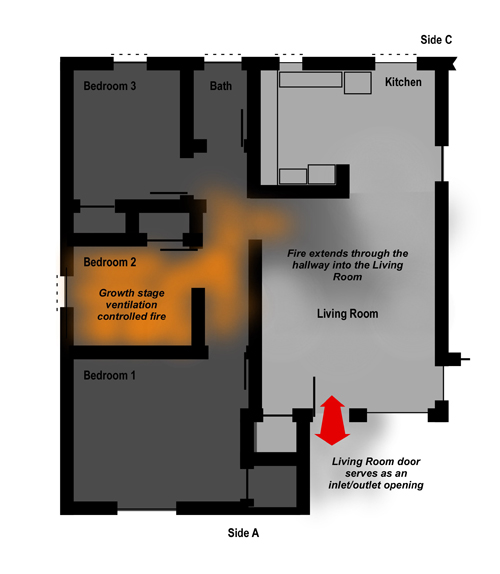

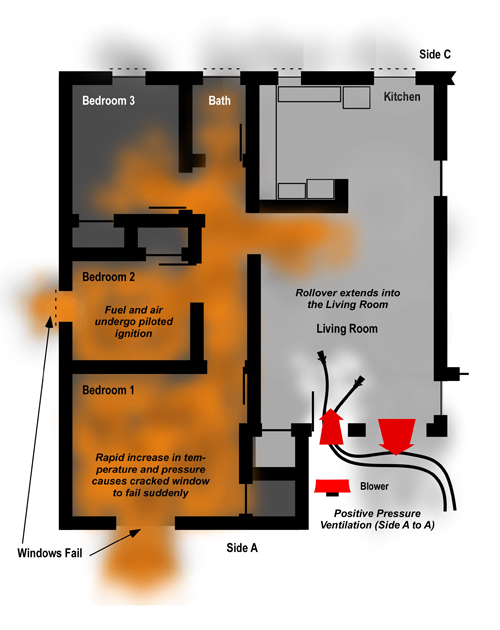

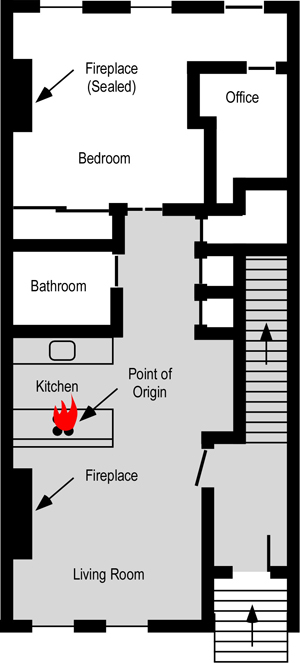

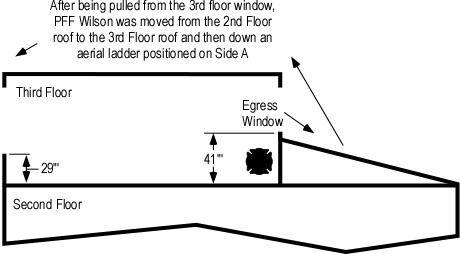

The crew of E70 (officer and firefighter) initiated fire attack through the door on Side A and advanced 3′-5′ (0.9-1.5 m) through the door and quickly knocked down flaming combustion in the living room and through dispatch, requested the first arriving truck to establish vertical ventilation. Retrieving a thermal imaging camera (TIC) from the apparatus, the crew of E70 began a left hand search (towards the bedrooms), but left the hoseline just inside the door on Side A (see Figure 1)

Figure 1. Floor Plan-149 Michelle Drive

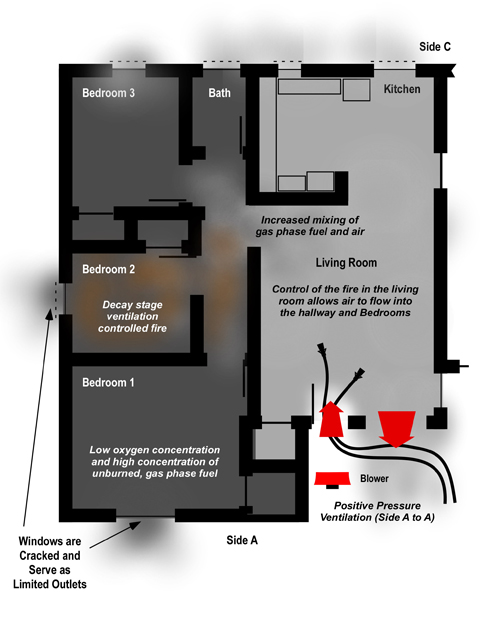

E73 hand stretched 200′ of 5″ (127 mm) supply line to a nearby hydrant. As he returned from the hydrant the firefighter from E73 observed a large volume of smoke from Side B. E73 officer tasked E70 engineer with placing a blower at the door on Side A. E73 (officer and firefighter) entered through the door on Side A and began a right hand search (taking the opposite direction from E70). E73 encountered poor visibility, but moderate temperature. While E73 conducted the search, E73 engineer shut off the natural gas service to the house.

E69 arrived at 0157 and prepared to perform vertical ventilation. The officer performed a size-up while the engineer obtained a chain saw and the firefighter placed a 14 ladder to provide access to the roof at the A/D corner. E70 engineer, asked the E69 officer about placing a blower to the front door (as previously ordered by the officer of E73) and he answered in the affirmative. The engineers from E70 and E73 placed a blower into operation 3′ (0.9 m) from the front door due to a half wall that partially enclosed the porch.

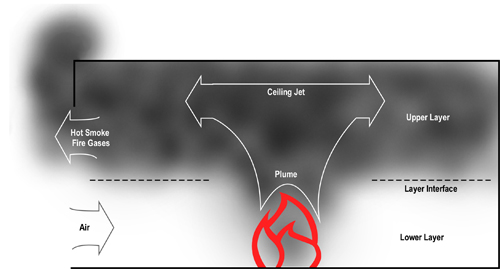

Note: No information is provided in the report regarding air track prior to or following pressurization of the building. The only substantive exhaust opening at the time the blower was placed into operation was the window in the living room immediately adjacent to the door on Side A.

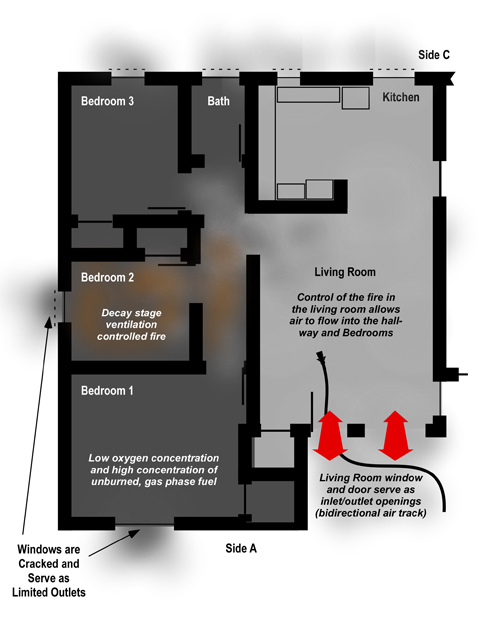

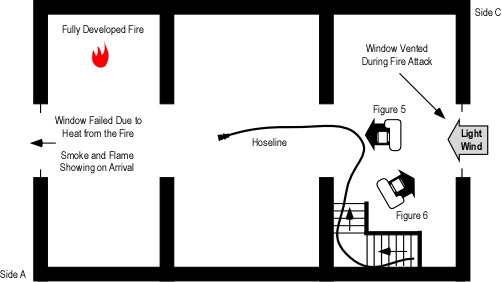

E73 located the first civilian casualty, a female occupant in the kitchen (see Figures 2 and 5). As they removed the victim, both visibility and temperature increased dramatically. As they move the victim through the living room, they observed rollover coming from the hallway leading to the bedrooms (see Figures 2 and 5). The E73 officer briefly operated the hoseline left in the living room by E70 to control flaming combustion in the upper layer. The blower was turned 90o to permit removal of the victim, but was then returned to its original operating position. E69 officer assigned the E69 firefighter to assist E73 with patient care on Side A.

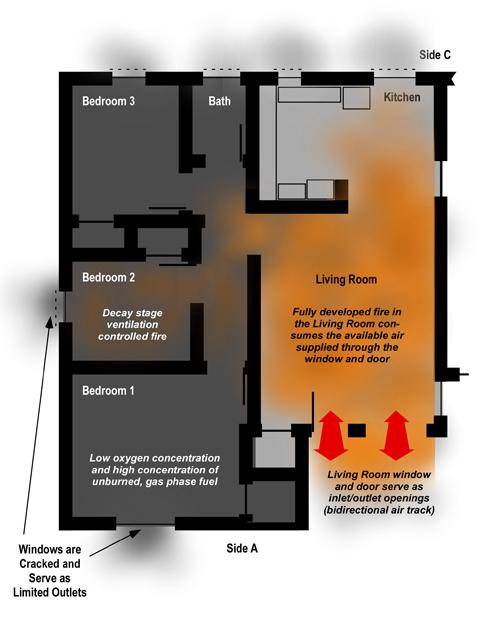

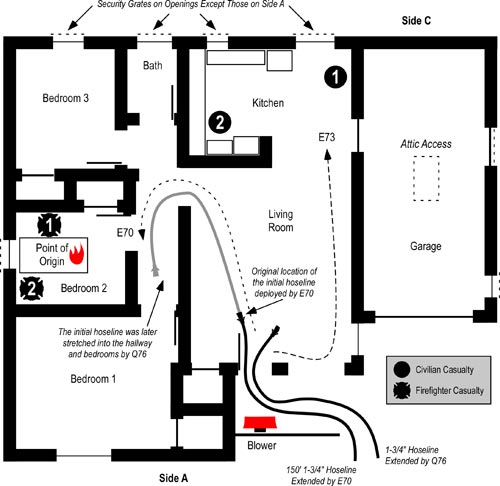

The E69 officer and engineer proceeded to the roof and began making a vertical ventilation opening on Side A roof, over the hallway. At 0159 Q76 arrived and while the officer was donning his breathing apparatus (BA), the window in Bedroom 1 failed suddenly followed by a significant increase in flaming combustion from the windows in Bedroom 1 and 2 on Sides A and B.

The firefighter from E73 who was providing emergency medical care to the civilian fire victim observed that the window in Bedroom 1 which had been cracked with some discharge of smoke, failed violently with glass blowing out onto the lawn and a large volume of flames venting from the window for a period of 10 to 15 seconds (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Extreme Fire Behavior

Note: Adapted from eight seconds of video was shot by Q76 firefighter from in front of Exposure D, looking towards the A/D corner of the fire building.

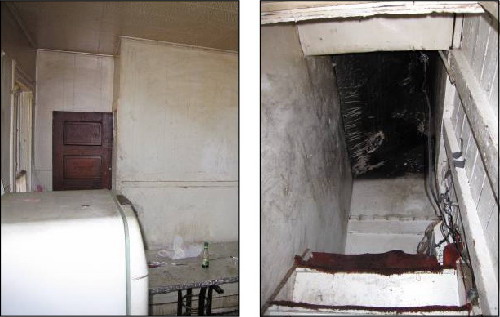

Figure 3. Post Fire Photo from in Front of Exposure D

Note: This screenshot from Google Maps Street View is from a similar angle as the video taken by Q76 firefighter and is provided to provide a point of reference and perspective for the video.

The E73 officer reentered the building and initiated fire attack using the hoseline left in the living room. E70 engineer stretched a second 150′ 1-3/4″ (45 m 45 mm) line to the front door. The second line was stretched into the building by Q76. Immediately after entering through the door on Side A, the Q76 met E73 officer who was exiting with low air alarm activation. Q76 took over the initial hoseline and worked their way down the hallway leading to the bedrooms, leaving the second line in the living room (see Figure 2) Q76 encountered poor visibility and high temperature with flames extending out of Bedrooms 1 and 2 and rollover in the hallway.

Shortly after exiting the building E73 officer advised E73 engineer that he was “out of air” [he was likely in a low air condition with low air alarm sounding rather than completely out of air] and expressed concern regarding E70’s air status.

Battalion 7 (BC7) arrived at 0202 and attempted to make face-to-face contact with Command (E70) as he had not heard E70 attempt to pass command to E74. At 0203, BC7 confirmed that a medic unit was responding and requested that the medic upgrade from Code 2 to Code 3. (Code 2 is a non-life threatening medical emergency requiring immediate response without the use of red lights or siren. Code 3 is a a medical emergency requiring immediate response with red lights and siren.) BC7 then attempted to contact E70 on the tactical channel and asked other crews operating at the incident about the status of E70. At 0205, BC7 ordered a second alarm and attempted to contact E70 on non-assigned tactical channels (in the event that their radios were inadvertently on the wrong channel). The second alarm added three engines (E74, E75, and E73) and a battalion chief (BC71) to the incident.

While BC7 was attempting to locate E70, Q76 was operating in the hallway and bedrooms in an effort to control the fire. They knocked the fire down in Bedroom 2 and controlled the rollover extending from Bedroom 1 down the hall. Q76 officer scanned Bedroom 2 with a TIC, but did not observe any victims. Q76 then advanced to Bedroom 1.

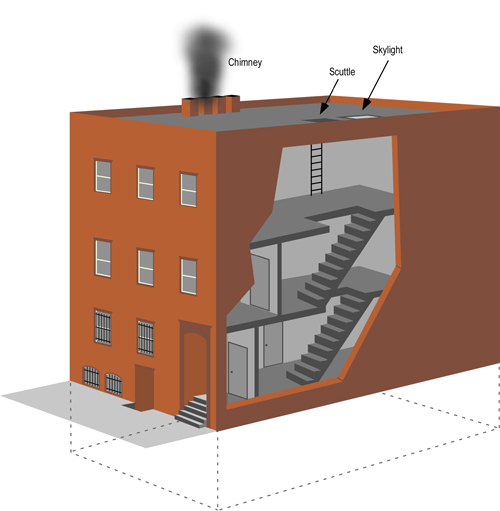

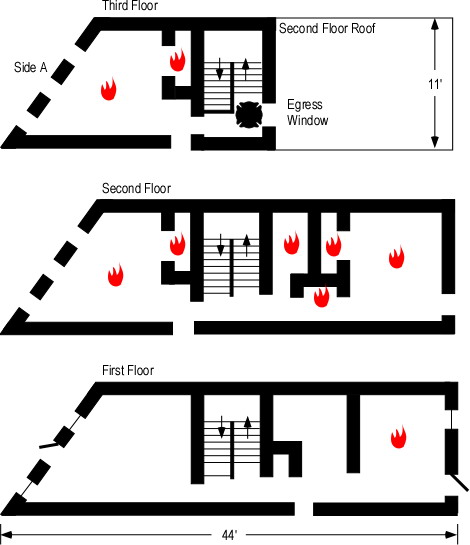

E69 completed a 6′ x 6′ (1.8 m x 1.8 m) ventilation opening in the roof on Side A, two thirds of the way from their access point at the A/D corner to Side B. Immediately after making the opening, they observed minimal smoke discharge (and were able to see items stored in the attic and the attic floor (original roof). They attempted to breach the attic floor, but were unable to do so (as it was constructed of 2″ x 6″ (51 mm x 152 mm) tongue and groove planks).

At 0206, after repeated unsuccessful attempts to contact E70, BC7 transmitted a report of a missing firefighter and assumed Command. Command requested an additional engine (E68) be added to the second alarm assignment. Battalion 64 (BC64) added himself to the incident and advised dispatch.

As E69 exited the roof they heard a loud pop and observed flames exiting the roof ventilation opening a distance of 8′-10′ (2.4-3.0 m). After knocking down the fire in Bedroom 1 Q76 moved back to Bedroom 2. Failure of the gypsum board on the wall between Bedrooms 1 and 2 allowed operation of the stream from their hoseline into both bedrooms.

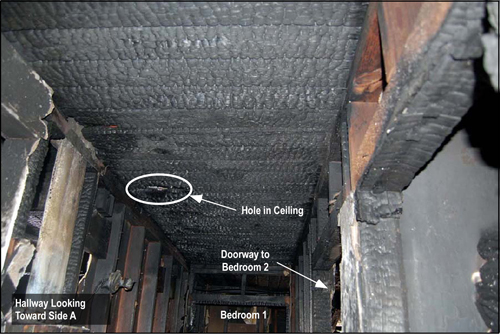

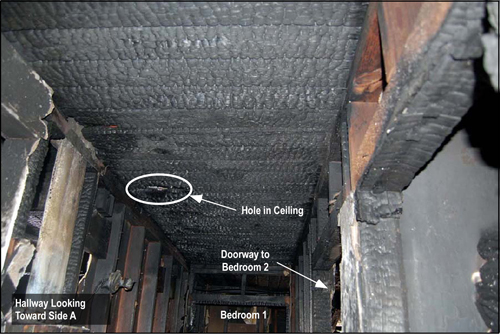

While at the doorway of Bedroom 2, Q76 observed a substantial volume of fire in the attic through a small hole in the hallway ceiling (see Figure 4) and attempted to apply water into the attic. However, their stream was ineffective.

Figure 4. Hallway Ceiling.

Note: Adapted from Contra Costa Fire Protection District Photos, Investigation Report: Michele Drive Line of Duty Deaths. Brightness and contrast adjusted to increase clarity.

After exiting the roof, E69 proceeded counter clockwise around the building to Side C where they removed window screens and broke out several panes of glass, but did not observe an appreciable discharge of smoke. Continuing around the B/C corner, E69 observed flames from the window of Bedroom 2 and the attic.

At 0208 Command (BC7) repeatedly attempted to contact E70 by radio on the tactical channel. Unsuccessful, he requested an additional Code 3 ambulance and advised that the status of the missing firefighters was unknown.

E69 met with Command (BC7) and was assigned to continue primary search for the second reported occupant. E69 firefighter and engineer began the search while the officer replaced his SCBA cylinder. As they entered, they picked up a hoseline (second 1-3/4″ (45 mm) hoseline) and used it to extinguish small areas of fire as they moved towards the kitchen. Q76 handed off their TIC to E69 as they exited the building with low air alarms sounding.

Q76 replaced SCBA cylinders and was tasked with search for E70 on the exterior. While conducting this search, they observed flames 10′-15′ (3.0-4.6 m) in length issuing from the gable vent on Side B.

After E69 officer rejoined his crew in the kitchen, they located the second civilian casualty who was determined to be diseased (see Figure 2). Command (BC7) ordered E69 to defer removing the victim and continue searching for E70.

Firefighter Rescue Operations

E69 walked through the interior of the dwelling looking for E70 and used a hoseline to knock down fire still burning in the closet of Bedroom 2. E69 advised command that E70 was not inside, but was instructed to conduct a second search of the interior.

At 0127, Command (BC7) asked dispatch to conduct a “head count” [personnel accountability report (PAR)]. Second alarm resources arrived between 0218 and 0221.

E69 reentered the building and conducted a thorough search for E70. At 0221, Command (BC7) ordered companies to “evacuate” [withdraw from] the building. Based on the urgency of his assignment to locate E70, E69 officer decided to continue the search into Bedroom 2. At approximately 0222, E69 located Captain Burton (fire service casualty 1) under debris on the right side of the bed (see Figure 2). His facepiece was still in place and his low air alarm was ringing slowly. E69 attempted to remove the Captain, but were only able to move him to the doorway to Bedroom 2 before smoke conditions worsened and visibility decreased. Near exhaustion, one member of the crew experience low air alarm activation and became disoriented requiring assistance to exit to the door on Side A.

Command (BC7) assigned Q76 to assist with the search. As E69 exited, they advised Q76 that they had located one member of E70 in the bedroom. After exiting, E69 advised Command (BC7) that they had located one member of E70 and that he appeared to be diseased and that they were having difficulty in removing him. Q76 quickly located Captain Burton inside the doorway of Bedroom 2 and removed him to Side A at 0228. E73 attempted resuscitation, but quickly determined that the Captain’s injuries were fatal.

BC64 and E76 officer continued the search in Bedroom 2 and located Engineer Desmond (fire service casualty 2) on the left side of the bed (see Figure 2). E72 assisted in controlling the fire in Bedroom 2 and the removal of the second member of E70 on a backboard. Engineer Desmond was removed from the building at approximately 0224. After both members of E70 were removed, crews removed the deceased civilian occupant.

Timeline

Review the Michelle Drive Timeline (PDF format) to gain perspective of sequence and the relationship between tactical operations and fire behavior.

Questions

The following questions focus on fire behavior, influence of tactical operations, and related factors involved in this incident.

- The E73 officer tasked E70 engineer with placement of a blower at the door on Side A (use of this tactic was reaffirmed by the E69 officer). What air track did this use of positive pressure create and what effect did this have on 1) conditions in the living room and kitchen and 2) in the hallway and bedrooms? Why do you think that this was the case?

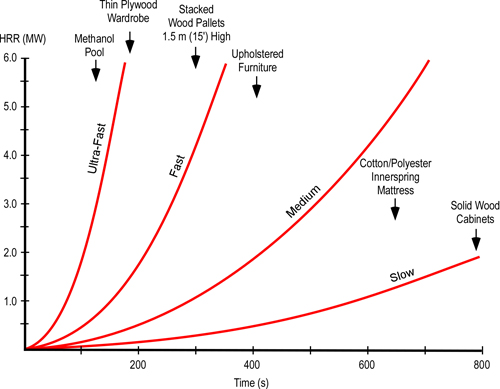

- What type of extreme fire behavior phenomena occurred in this incident? Do you agree with the Contra Costa County Fire Protection District report conclusion that this was a fire gas ignition or do you suspect that some other phenomenon was involved?

- How did the conditions necessary for this extreme fire behavior event develop (address both the fuel and ventilation sides of the equation)?

- What was the initiating event(s) that lead to the occurrence of the extreme fire behavior that trapped Captain Burton and Engineer Desmond? How did the use of positive pressure ventilation influence the occurrence of the extreme fire behavior (if in fact it did)?

- What action could have been taken to reduce the potential for extreme fire behavior and maintain tenable conditions during primary search operations?

- How did building design and construction impact on fire behavior and tactical operations during this incident?

Ed Hartin, MS, EFO, MIFireE, CFO

References

Contra Costa County Fire Protection District. (2008). Investigation Report: Michele Drive Line of Duty Deaths. Retrieved February 13, 2009 from http://www.cccfpd.org/press/documents/MICHELE%20LODD%20REPORT%207.17.08.pdf

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (2009). Death in the Line of Duty Report 2007-28. Retrieved May 5, 2009 from http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/fire/pdfs/face200728.pdf.