Influence of Ventilation in Residential Structures: Tactical Implications Part 3

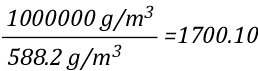

Sunday, July 17th, 2011UL’s third tactical implication is that there may be little smoke showing when a fire initially enters the decay stage as a result of limited ventilation. These fire conditions may present similar indicators to an incipient fire. However, fire conditions and the hazards presented to firefighters are considerably different.

Visible Indications of Fire Development

In Reading the Fire: B-SAHF, I introduced Building, Smoke, Air Track, Heat, and Flame (B-SAHF) as an organizing scheme for fire behavior indicators. Use of a standardized and organized approach to reading the fire can improve our ability to assess current fire conditions and predict likely fire development and changes that may occur.

Station Officer Shan Raffel of Queensland (Australia) Fire Rescue recently published an excellent article titled The Art of Reading Fire on the FirefighterNation website that provides another view of the B-SAHF indicators and Reading the Fire.

Building factors (particularly the normal ventilation profile, size and compartmentation, and thermal characteristics) can have a significant impact on fire development and how fire conditions present from the exterior of the building. However, this UL tactical implication relates most closely to Smoke and Air Track as well as somewhat indirectly to Heat (but this is the key to understanding what is happening). First a quick review of these key indicators

Smoke: What does the smoke look like and where is it coming from? This indicator can be extremely useful in determining the location and extent of the fire. Smoke indicators may be visible on the exterior as well as inside the building.

Air Track: Related to smoke, air track is the movement of both smoke (generally out from the fire area) and air (generally in towards the fire area).

Heat: This includes a number of indirect indicators. Heat cannot be observed directly, but you can feel changes in temperature and may observe the effects of heat on the building and its contents. Visual clues such as crazing of glass and visible pyrolysis from fuel that has not yet ignited are also useful heat related indicators. Important: Temperature influences smoke and air track indicators such as volume and velocity of smoke discharge.

For a more detailed look at B-SAHF and reading the fire, see the following posts:

How to Improve Your Skills

Building Factors

Building Factors Part 2

Building Factors Part 3

Smoke Indicators

Smoke Indicators Part 2

Air Track Indicators

Air Track Indicators Part 2

Heat Indicators

Heat Indicators Part 2

Heat Indicators Part 3

Flame Indicators

Flame Indicators Part 2

Incipient Stage Fires: Key Fire Behavior Indicators

Growth Stage Fires: Key Fire Behavior Indicators

Fully Developed Fires: Key Fire Behavior Indicators

Decay Stage Fires: Key Fire Behavior Indicators

Stages of Fire Development, Burning Regime, Smoke, Air Track & Heat

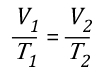

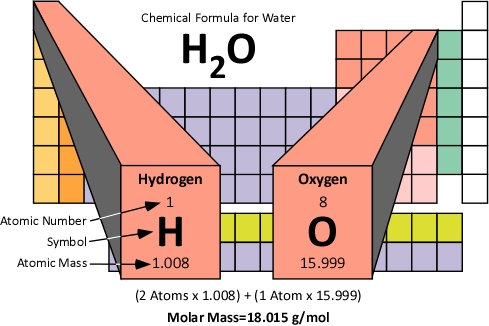

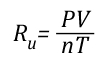

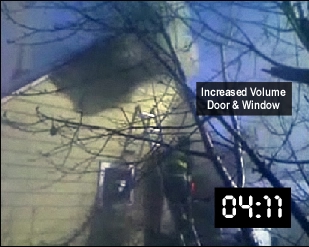

While the “stages of fire” have been described differently in fire service textbooks the phenomenon of fire development is the same. For our purposes, the stages of fire development in a compartment will be described as incipient, growth, fully developed and decay (see Figure 1). Despite dividing fire development into four “stages” the actual process is continuous with “stages” flowing from one to the next. While it may be possible to clearly define these transitions in the laboratory, in the field it is often difficult to tell when one ends and the next begins.

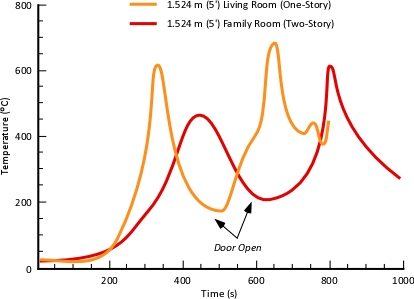

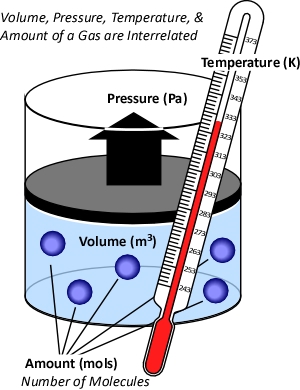

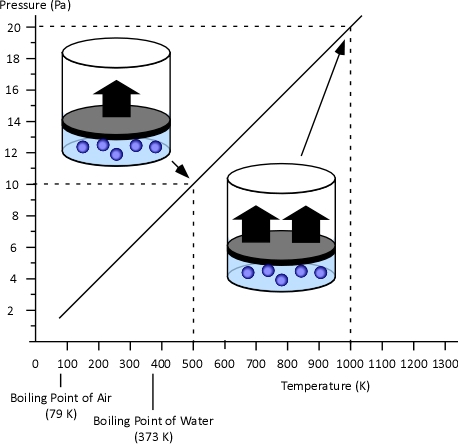

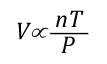

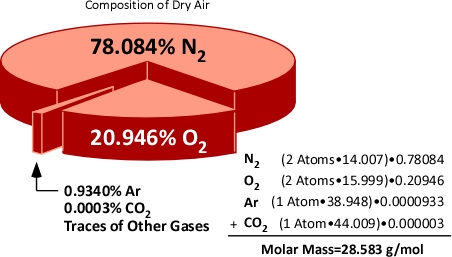

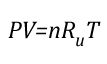

Understanding the stages of fire development is important, but this only provides a limited picture of fire development in a compartment. Conversion of chemical potential energy from fuel depends on availability of adequate oxygen for the combustion reaction to occur. As the ambient air in the compartment provides adequate oxygen, in incipient stage and early growth stage, heat release rate is limited by the chemical and physical characteristics of the fuel. This condition is known as a fuel controlled burning regime. In a compartment fire, combustion occurs in an enclosure where the air available for combustion is limited by 1) the volume of the compartment and 2) ventilation. Ventilation in a compartment fire is limited (particularly if doors and windows are closed and intact), as the fire grows and heat release rate increases, so too does demand for oxygen. When fire growth is limited by the available oxygen, heat release rate is slowed and then diminishes. This condition is known as a ventilation controlled burning regime.

Many if not most fires that have progressed beyond the incipient stage when the fire department arrives are ventilation controlled. This means that the heat release rate (the fire’s power) is limited by the existing ventilation. If ventilation is increased, either through tactical action or unplanned ventilation resulting from effects of the fire (e.g., failure of a window) or human action (e.g., exiting civilians leaving a door open), heat release rate will increase (see Figure 1)

Figure 1. Fire Development Curve (Fuel and Ventilation Controlled Regimes)

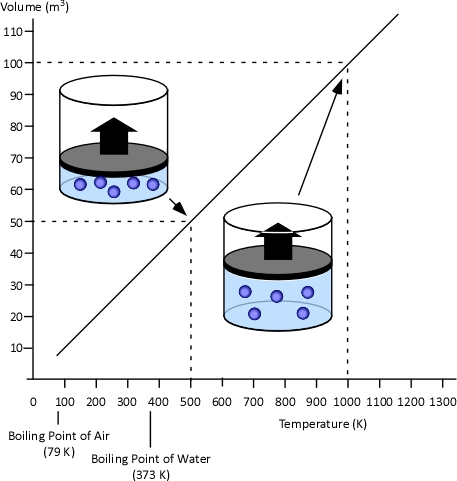

Several things happen as a compartment fire develops: Heat release rate increases, smoke production increases, and pressure within the compartment increases proportionally to the absolute temperature. These conditions result in a number of fire behavior indicators that may be visible from the exterior of the building. As a fire moves from the Incipient to the Growth Stage, an increasing volume of smoke may be visible from the exterior (Smoke Indicator) and the velocity of smoke discharge will likely increase (Air Track Indicator and indirect Heat Indicator).

It is a reasonably logical conclusion that a smaller volume of smoke and lower velocity of smoke discharge will be observed in incipient and early growth stage fires and the volume and velocity of smoke discharge will increase as the fire develops. However, what happens when the fire becomes ventilation controlled?

Influence of Ventilation on Residential Fire Behavior

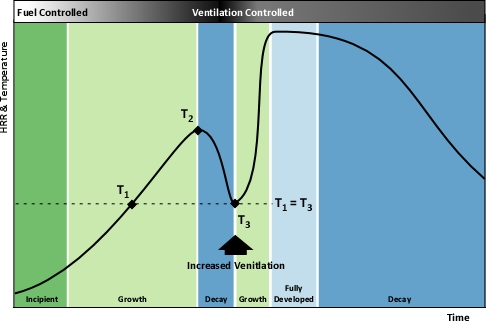

Earlier this year, Underwriters Laboratories (UL) conducted a series of full-scale experiments to determine the influence of ventilation on fire behavior in legacy and contemporary residential construction (see Did You Ever Wonder? and UL Ventilation Course).

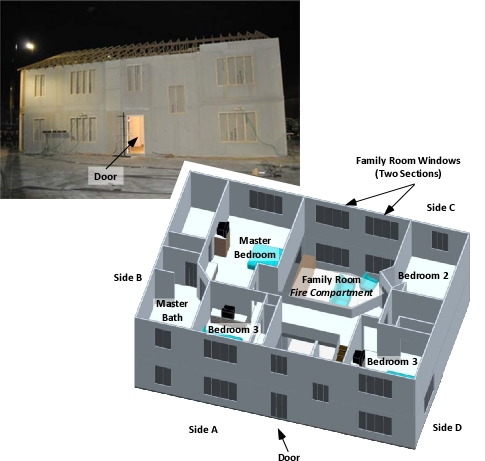

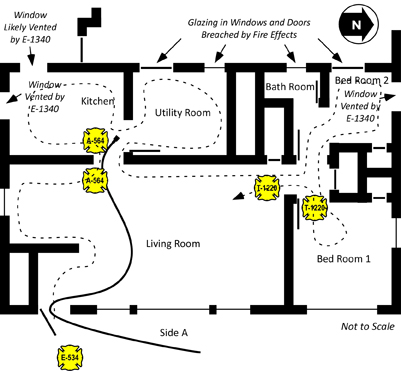

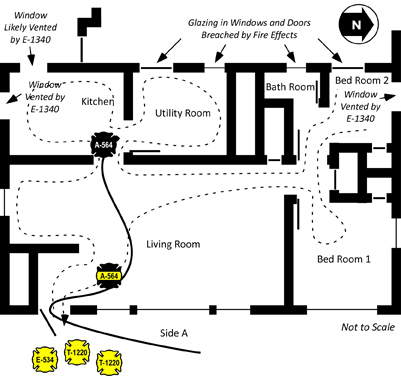

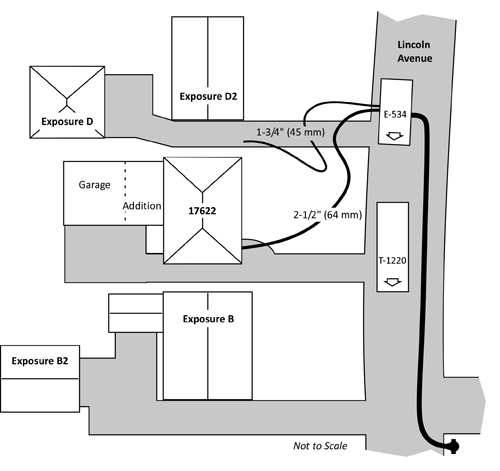

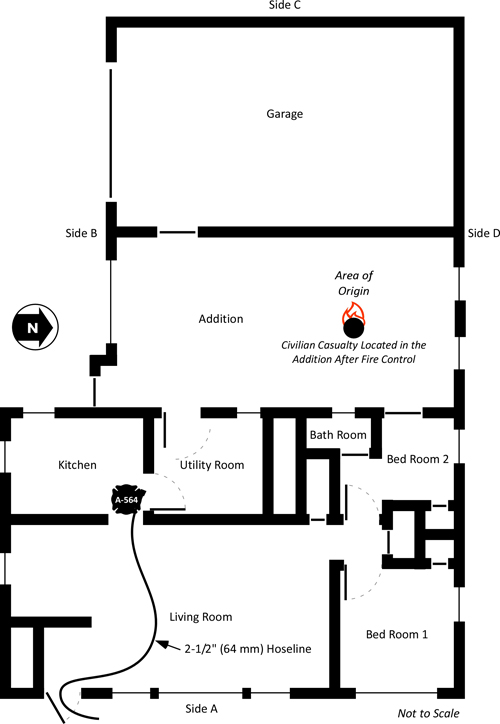

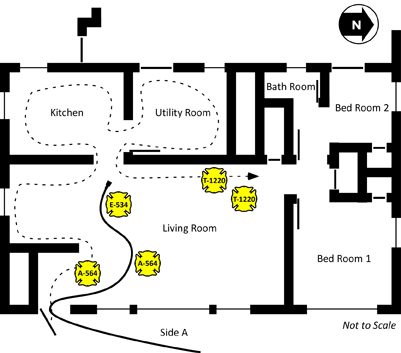

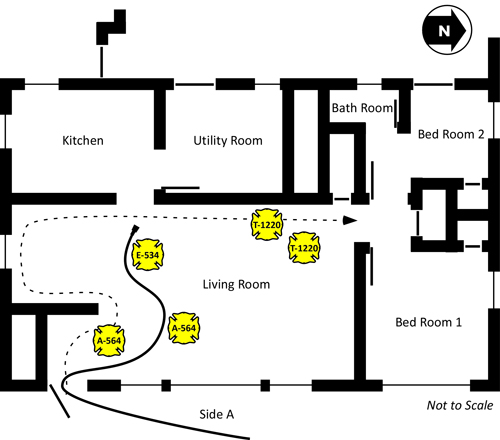

These tests were conducted in full-scale one and two-story, wood-frame structures constructed inside the UL laboratory in Northbrook, IL. Fires in the one-story structure were all started in the living room (see Figure 2) and involved typical contents found in a single-family home.

Figure 2: One-Story Structure and Floor Plan

As discussed in UL Tactical Implications Part 1 and Part 2, each of the fires during these tests quickly became ventilation controlled due to the fuel load within the buildings and limited ventilation provided by closed and intact doors and windows.

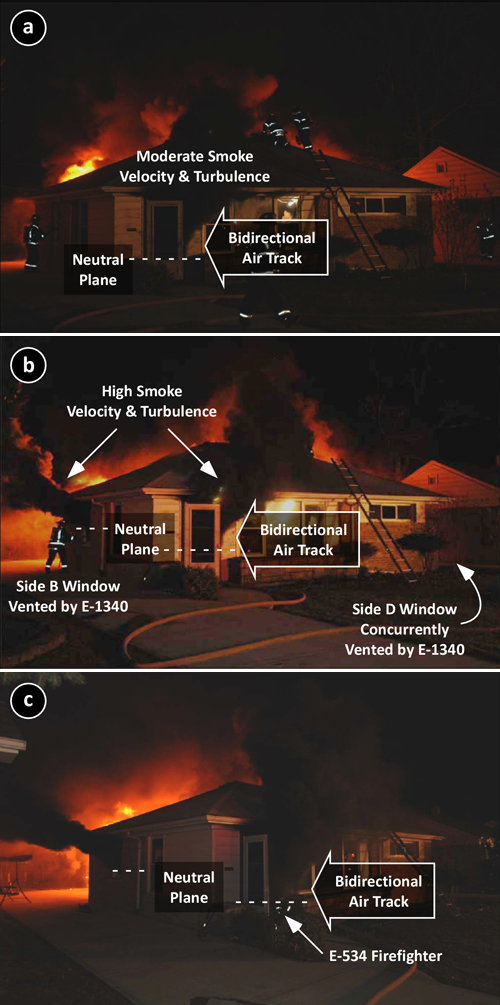

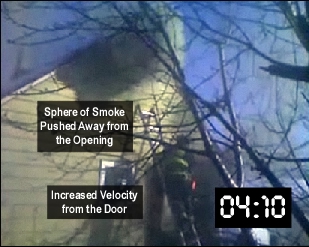

As each fire developed, the volume of smoke visible from the exterior and velocity of smoke discharge increased. This is consistent with fire development within the structure and increasing heat release rate, temperature, and volume of smoke production from the developing fire. Figure 3 illustrates exterior conditions at 05:05 during Test 5 conducted in the one-story residence.

Figure 3: Conditions at 05:05 (UL Test 5)

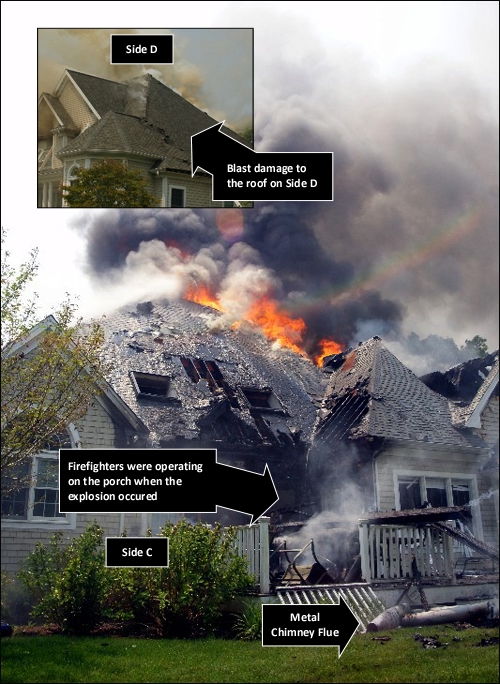

Interestingly, as the fire became ventilation controlled (as determined by both measurement of oxygen concentration and the heat release rate in the building), the volume and velocity of smoke discharge decreased to a negligible level as illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4: Conditions at 05:34 (UL Test 5)

This change occurred within a matter of 30 seconds! How might this influence firefighters’ perception of fire conditions inside the building if they arrived at 05:34 rather than 05:04? While presenting much the same as an incipient or early growth stage fire, conditions within the building at 05:34 are significantly ventilation controlled and increased ventilation resulted in rapid fire development and transition through flashover to a fully developed fire.

NIST Phoenix Warehouse Tests

In the Hazard of Ventilation Controlled Fires, I discussed a series of tests conducted by the National Institute for Standards and Technology (NIST) at an ordinary constructed warehouse in Phoenix, AZ. These tests were intended to develop information about performance of ordinary constructed buildings related to structural collapse. However, they also provided some interesting information regarding fire behavior.

One of the tests involved a fire in the front section of the warehouse that measured 50’ x 90’ (15.2 m x 27.4 m) with a height of 15’ (4.6 m) to the top of the pitched truss roof. The fuel load for this test included four stacks of 10 wood pallets and the interior finish and combustible structural elements of the building. All doors and windows were closed at the start of the test.

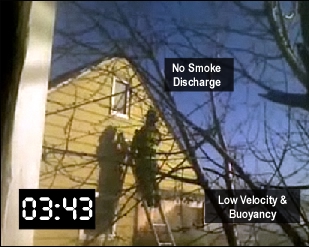

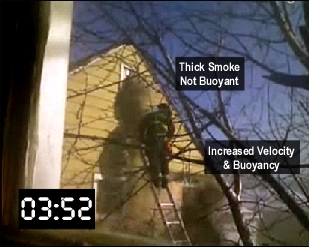

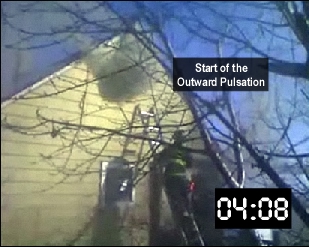

Figure 5 illustrates a large volume of dark gray to black smoke discharging from the roof of the structure and flames visible from roof ventilators at 03:57. The B-SAHF indicators visible n this photo indicate a significant growth stage fire within this building.

Figure 5. Conditions at 03:57 (NIST Warehouse Test)

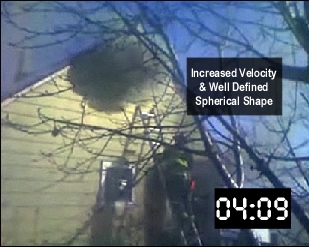

However, at 05:31 conditions visible on the exterior are quite different. The color and volume of smoke discharge (Smoke Indicators) as well as the velocity of discharge (Air Track Indicator) may lead firefighters to believe that this is an incipient or early growth stage fire. Nothing could be further from the truth. This fire is in the decay stage as a result of limited ventilation and any increase in ventilation will result in a rapid and significant increase in heat release rate!

Figure 6. Conditions at 05:31 (NIST Warehouse Test)

For more information on these tests see Structural Collapse Fire Tests: Single Story, Ordinary Construction Warehouse (Stroup, Madrzykowski, Walton, & Twilley, 2003) or view the videos of this series of tests at the NIST Structural Collapse webpage.

The Key

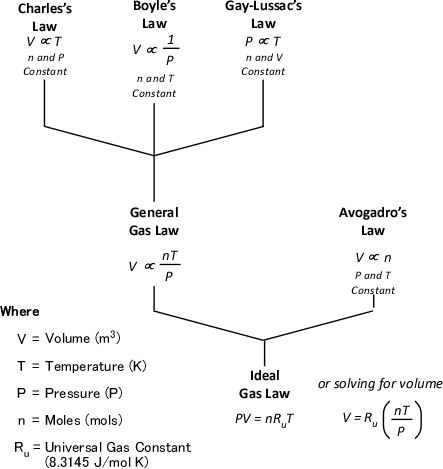

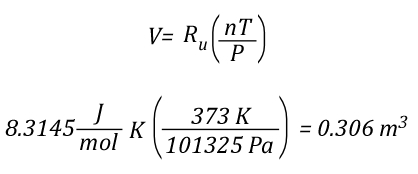

Heat release rate and temperature drop as the fire becomes ventilation controlled. Volume and velocity of smoke discharge are a function of pressure (given a constant opening size). Reduction in temperature and corresponding reduction in pressure will result in a smaller volume and lower velocity of smoke discharge.

When the temperature is the same, the velocity of discharge will likely be similar. Figure 1 shows that the temperature inside a compartment may be the same during the growth and decay stages of the fire. If the ventilation profile (number, size, and location of openings) remains the same, similar Smoke and Air Track indicators can be present.

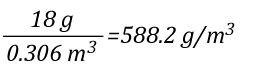

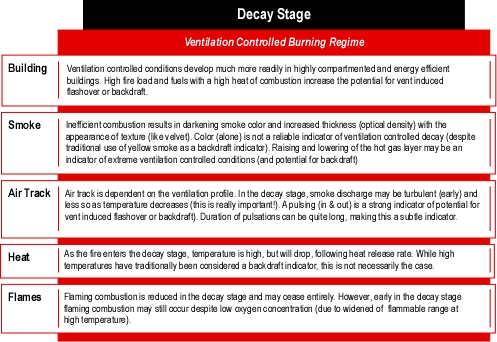

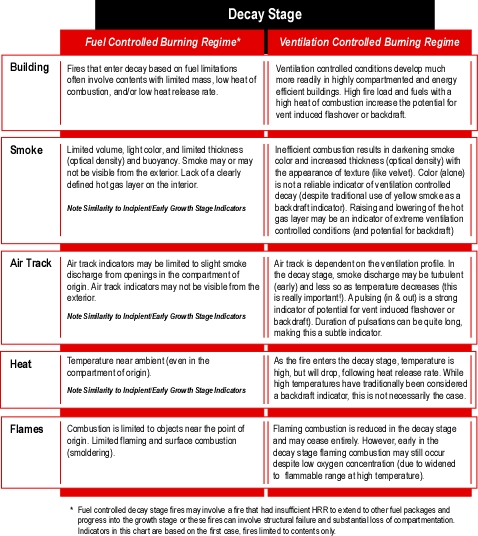

Decay stage incidators may be subtle. Consider the full range of B-SAHF inciators that may be observed under ventilation controlled, decay stage conditions (see Figure 7.

Figure 7. B-SAHF Decay Stage Indicators.

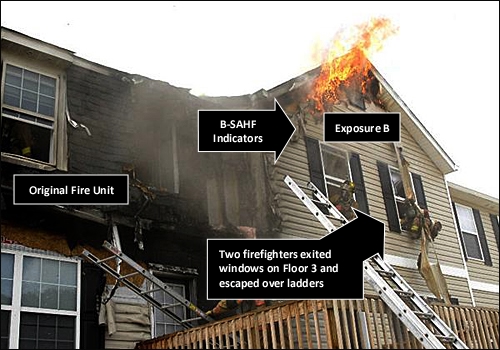

Durango, Colorado Commercial Fire

CFBT-US developed a case study examining an extreme fire behavior event that occurred during a commercial fire in Durango, CO in 2008 injuring nine firefighters and fire officers. The reporting party indicated that there was a large amount of dark smoke coming from the roof of the building. However, when firefighters arrived, they found nothing showing but a small amount of light colored smoke. Why might this have been the case?

Download a copy of the Fire Behavior Case Study: Durango CO Commercial Fire and see if this may have been a result of similar fire development and presentation of fire behavior indicators as seen in the UL and NIST tests!

Ed Hartin, MS, EFO, MIFireE, CFO

References

Kerber, S. (2011). Impact of ventilation on fire behavior in legacy and contemporary residential construction. Retrieved July 16, 2011 from http://www.ul.com/global/documents/offerings/industries/buildingmaterials/fireservice/ventilation/DHS%202008%20Grant%20Report%20Final.pdf.

Stroup, D., Madrzykowski, D., Walton, W., & Twilley, W. (2003). Structural collapse fire tests: Single story, ordinary construction warehouse, NISTIR 6959. Retrieved July 16, 2011 from http://www.nist.gov/customcf/get_pdf.cfm?pub_id=861215