Townhouse Fire: Washington, DC

Extreme Fire Behavior

This post continues study of an incident in a townhouse style apartment building in Washington, DC with examination of the extreme fire behavior that took the lives of Firefighters Anthony Phillips and Louis Mathews.

A Quick Review

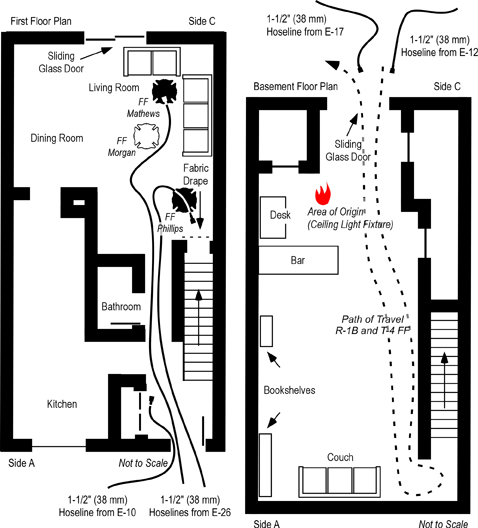

Prior posts in this series, Fire Behavior Case Study of a Townhouse Fire: Washington, DC and Townhouse Fire: Washington, DC-What Happened examined the building and initial tactical operations at this incident. The fire occurred in the basement of a two-story, middle of building, townhouse style apartment with a daylight basement. This configuration provided an at grade entrance to the Floor 1 on Side A and at grade entrance to the Basement on Side C.

Engine 26, the first arriving unit reported heavy smoke showing from Side A and observed a bi-directional air track at the open front door. First alarm companies operating on Side A deployed hoselines into the first floor to locate the fire. Engine 17, the second due engine, was stretching a hoseline to Side C, but had insufficient hose and needed to extend their line. Truck 4, the second due truck, operating from Side C opened a sliding glass door to the basement to conduct search and access the upper floors (prior to Engine 17’s line being in position). When the door on Side C was opened, Truck 4 observed a strong inward air track. As Engine 17 reached Side C (shortly after Rescue 1 and a member of Truck 4 entered the basement) and asked for their line to be charged, and Engine 17 advised Command that the fire was small.

Extreme Fire Behavior

Proceeding from their entry point on Side C towards the stairway to Floor 1 on Side A, Rescue 1B and the firefighter from Truck 4 observed fire burning in the middle of the basement room. Nearing the stairs, temperature increased significantly and they observed fire gases in the upper layer igniting. Rescue 1B and the firefighter from Truck 4 escaped through the basement doorway on Side C as the basement rapidly transitioned to a fully developed fire.

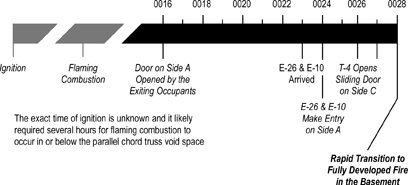

Figure 1. Timeline Leading Up to the Extreme Fire Behavior Event

The timeline illustrated in Figure 1 is abbreviated and focuses on a limited number of factors. A detailed timeline, inclusive of tactical operations, fire behavior indicators, and fire behavior is provided in a subsequent section of the case.

After Engine 17’s line was charged, the Engine 17 officer asked Command for permission to initiate fire attack from Side C. Command denied this request due to lack of contact with Engines 26 and 10 and concern regarding opposing hoselines. Due to their path of travel around Side B of the building, Engine 17 had not had a clear view of Side A and thought that they were at a doorway leading to Floor 1 (rather than the Basement). At this point, neither the companies on Side C nor Command recognized that the building had three levels on Side C and two levels on Side A.

At this point crews from Engine 26 and 10 are operating on Floor 1 and conditions begin to deteriorate. Firefighter Morgan (Engine 26) observed flames at the basement door in the living room (see Figure 8 which illustrates fire conditions in the basement as seen from Side C). Firefighter Phillips (Engine 10) knocked down visible flames at the doorway, but conditions continued to deteriorate. Temperature increased rapidly while visibility dropped to zero.

As conditions deteriorated, Engine 26’s officer feels his face burning and quickly exits (without notifying his crew). In his rapid exit through the hallway on Floor 1, he knocked the officer from Engine 10 over. Confused about what was happening Engine 10’s officer exited the building as well (also without notifying his crew). Engine 26’s officer reports to Command that Firefighter Mathews was missing, but did not report that Firefighter Morgan was also missing. Appearing dazed, Engine 10’s officer did not report that Firefighter Phillips was missing.

Figure 2. Conditions on Side C at Aproximately 00:28

Note: From Report from the Reconstruction Committee: Fire at 3146 Cherry Road NE, Washington DC, May 30, 1999, p. 32. District of Columbia Fire & EMS, 2000.

Figure 3. Conditions on Side A at Aproximately 00:28

Note: From Report from the Reconstruction Committee: Fire at 3146 Cherry Road NE, Washington DC, May 30, 1999, p. 29. District of Columbia Fire & EMS, 2000.

Firefighter Rescue Operations

After the exit of the officers from Engine 26 and Engine 10, the three firefighters (Mathews, Phillips, and Morgan) remained on Floor 1. However, neither Command (Battalion 1) nor a majority of the other personnel operating at the incident recognized that the firefighters from Engines 26 and 10 had been trapped by the rapid extension of fire from the Basement to Floor 1 (see Figure 4).

While at their apparatus getting a ladder to access the roof from Side B, Truck 4B observed the rapid fire development in the basement and pulled a 350′ 1-1/2″ (107 m 38 mm) line from Engine 12 to Side C, backing up Engine 17.

Figure 4. Location of Firefighters on Floor 1

Note: Adapted from Report from the Reconstruction Committee: Fire at 3146 Cherry Road NE, Washington DC, May 30, 1999, p. 18 & 20. District of Columbia Fire & EMS, 2000 and Simulation of the Dynamics of the Fire at 3146 Cherry Road NE, Washington D.C., May 30, 1999, p. 12-13, by Daniel Madrzykowski & Robert Vettori, 2000. Gaithersburg, MD: National Institute of Standards and Technology.

Engine 17 again contacted Command (Battalion 1) and requested permission to initiate an exterior attack from Side C. However, the officer of Engine 17 mistakenly advised Command that there was no basement entrance and that his crew was in position to attack the fire on Floor 1. Unable to contact Engines 10 and 26, Command denied this request due to concern for opposing hoselines. With conditions worsening, Command (Battalion 1) requested a Task Force Alarm at 00:29, adding another two engine companies, truck company, and battalion chief to the incident.

Firefighter Phillips (E-10) attempted to retreat from his untenable position at the open basement door. He was only able to travel a short distance before he collapsed. Firefighter Morgan (E-26) heard a loud scream to his left and then a thud as if someone had fallen to the floor (possibly Firefighter Mathews (E-26)). Firefighter Morgan found the attack line and opened the nozzle on a straight stream, penciling the ceiling twice before following the hoseline out of the building (to Side A). Firefighter Morgan exited the building at approximately 00:30.

Rescue 1B entered the structure on Floor 1, Side A to perform a primary search. They crawled down the hallway on Floor 1 towards Side C until they reached the living room and attempted to close the open basement door but were unable to do so. Rescue 1 B did not see or hear Firefighters Mathews (E-26) and Phillips (E-10) while working on Floor 1. Rescue 1B noted that the floor in the living room was spongy. The Rescue 1 Officer ordered his B Team to exit, but instead they returned to the front door and then attempted to search Floor 2, but were unable to because of extremely high temperature.

Unaware that Firefighter Phillips (E-10) was missing, Command tasked Engine 10 and Rescue 1A, with conducting a search for Firefighter Mathews (E-26). The Engine 10 officer entered Floor 1 to conduct the search (alone) while instructing another of his firefighters to remain at the door. Rescue 1A followed Engine 26’s 1-1/2″ (38 mm) hoseline to Floor 1 Slide C. Rescue 1B relocated to Side B to search the basement for the missing firefighter.

The Engine 26 Officer again advised Command (Battalion 1) that Firefighter Mathews was missing. Engine 17 made a final request to attack the fire from Side C. Given that a firefighter was missing and believing that the fire had extended to Floor 1, Command instructed Engine 17 to attack the fire with a straight stream (to avoid pushing the fire onto crews working on Floor 1). At approximately 00:33, Battalion 2 reported (from Side C) that the fire was darkening down. Engine 14 arrived and staged on Bladensburg Road.

Command ordered a second alarm assignment at 00:34 hours. At 00:36, Command ordered Battalion 2 (on Side C) to have Engine 17 and Truck 4 search for Firefighter Mathews in the Basement. Engine 10’s officer heard a shrill sound from a personal alert safety system (PASS) and quickly located Firefighter Phillips (E-10). Firefighter Phillips was unconscious, lying on the floor (see Figure 4) with his facepiece and hood removed. Unable to remove Firefighter Phillips by himself, the officer from Engine 10 unsuccessfully attempted to contact Command (Battalion 1) and then returned to Side A to request assistance.

Command received a priority traffic message at 00:37, possibly attempting to report the location of a missing firefighter. However, the message was unreadable.

The Hazmat Unit and Engine 6 arrived and staged on Bladensburg Road and a short time later were tasked by Command to assist with rescue of the downed firefighter on Floor 1. Firefighter Phillips (E-10) was removed from the building by the Engine 10 officer, Rescue 1A, Engine 6, and the Hazardous Materials Unit at 00:45. After Firefighter Phillips was removed to Side A, Command discovered that Firefighter Mathews (E-26) was still missing and ordered the incident safety officer to conduct an accountability check. Safety attempted to conduct a personnel accountability report (PAR) by radio, but none of the companies acknowledged his transmission.

The Deputy Chief of the Firefighting Division arrived at 00:43 and assumed Command, establishing a fixed command post at the Engine 26 apparatus. Battalion 4 arrived a short time later and was assigned to assist with rescue operations along with Engines 4 and 14.

Firefighter Mathews was located simultaneously by several firefighters. He was unconscious leaning over a couch on Side C of the living room (see Figure 4). Firefighter Mathews breathing apparatus was operational, but he had not activated his (non-integrated) personal alert safety system (PASS). Firefighter Mathews was removed from the building by Engine 4, Engine 14, and Hazardous Materials Unit at 00:49.

Command (Deputy Chief) ordered Battalions 2 and 4 to conduct a face-to-face personnel accountability report on Sides A and C at 00:53.

Questions

- Based on the information provided in the case to this point, answer the following questions:

- National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) Death in the Line of Duty Reports examining incidents involving extreme fire behavior often recommend close coordination of fire attack and ventilation.

- Did the fire behavior in this incident match the prediction you made after reading the previous post (Towhouse Fire: Washington DC-What Happened)?

- What type of extreme fire behavior occurred? Justify your answer?

- What event or action initiated the extreme fire behavior? Why do you believe that this is the case?

- How did building design and construction impact on fire behavior and tactical operations during this incident?

- How might a building pre-plan and/or 360o reconnaissance have impacted the outcome of this incident? Note that 360o reconnaissance does not necessarily mean one individual walking completely around the building, but requires communication and knowledge of conditions on all sides of the structure (e.g., two stories on Side A and three stories on Side C).

- How might the outcome of this incident have changed if Engine 17 had been in position and attacked the fire in the basement prior to Engines 26 and 10 committing to Floor 1?

- What strategies and tactics might have been used to mitigate the risk of extreme fire behavior during this incident?

More to Follow

This incident was one of the first instances where the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) Fire Dynamics Simulator (FDS) was used in forensic fire scene reconstruction (Madrzykowski & Vettori, 2000). Modeling of the fire behavior in this incident helps illustrate what was likely to have happened in this incident. The next post in this series will examine and expand on the information provided by modeling of this incident.

Ed Hartin, MS, EFO, MIFireE, CFO

References

District of Columbia (DC) Fire & EMS. (2000). Report from the reconstruction committee: Fire at 3146 Cherry Road NE, Washington DC, May 30, 1999. Washington, DC: Author.

Madrzykowski, D. & Vettori, R. (2000). Simulation of the Dynamics of the Fire at 3146 Cherry Road NE Washington D.C., May 30, 1999, NISTR 6510. August 31, 2009 from http://fire.nist.gov/CDPUBS/NISTIR_6510/6510c.pdf

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). (1999). Death in the line of duty, Report 99-21. Retrieved August 31, 2009 from http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/fire/reports/face9921.html

Tags: burning regime, case study, deliberate practice, Extreme Fire Behavior, fire development, firefighter fatality, firefighter injury, firefighter LODD, flashover, NIOSH, NIST, practical fire dynamics, reading the fire, situational awareness, structural firefighting, Tactical Ventilation, vent controlled fire

September 28th, 2009 at 13:56

[…] Case Study of a Townhouse Fire: Washington, DC, Townhouse Fire: Washington, DC-What Happened,and Townhouse Fire: Washington, DC-Extreme Fire Behavior examined the building and initial tactical operations at this incident. The fire occurred in the […]